By Kyla Yein

Since Barbie as Rapunzel came out, I’ve been an avid fan of the fairytale – which only increased with the release of Tangled. Actually, Rapunzel was the first story for which I’d read the original fairytale as a child so this story has always been special. So I decided to make my project 3 Rapunzel-themed. I’ve organized it so that my project has four parts to it, each from the perspective of a different key character in the story.

~ A dish that works to symbolize Rapunzel’s situation, both physically and mentally

~ A rewritten song/lullaby from the perspective of Rapunzel’s biological mother, describing her experiences

~ A poster by the witch (“Mother Gothel”) that attempts to sell her vegetables for first-borns

~ A diary entry “written by” Rapunzel describing her thoughts throughout the fairytale

These various parts of the project are structured within a cootie catcher. Cootie catchers are origami fortune tellers that many children use – and thus an aspect of our childhood that many of us relate to. I aim to transport the audience to their childhood and evoke emotions of nostalgia throughout the project. In order to move on to the next part, simply keep going until the end of the abstract and there will be a link to return to the choices (to access a different part of the project) or to end.

EXPOSING OBSESSIONS WITH SURVIVAL STORIES

Over quarantine, like many others, I have turned to Netflix as my main source of entertainment – and comfort. Around Thanksgiving time Netflix added two seasons of the hit reality show Survivor, and it probably took me about three days to finish all 29 episodes, each of which are about 45 minutes long. Insane – I know – but I’m also the girl who watched all ten seasons of Friends in one month, so… not surprising. I was, however, surprised at how much I loved seeing people suffer. I know, I know, I know that sounds really messed up, but hear me out. There’s something about survival stories that is just so enticing and exciting.

Before we get into the nitty gritty of my super messed up mind, let me introduce what actually happens on Survivor. Each season there are about 16-20 contestants, referred to as “castaways”, all of which spend up to 39 days competing for the title of “Sole Survivor”, but even more so for the $1 million prize. The castaways arrive on an island in Fiji where they’re split into two or three different tribes (depending on the season and number of contestants) and are completely stripped from any luxuries they may have had back home. When they arrive at their campsites they have to build shelter from scratch, account for their own food, and account for their own bathroom and waste. They also never get a change of clothes or any hygiene products, so these people are literally in the same underwear and don’t brush their teeth for a total of 39 days or up to however long they last. And to top it all off, they’re playing a ruthless game of intellectual survival filled with deceit, lies, and paranoia. And yet, for the audience, it’s absolutely thrilling.

Twice every three days, the contestants meet for challenges, some of which are physical while others are more mental, but most of the time they’re both. There are two types of challenges: Reward Challenges and Immunity Challenges. The first ends in a reward for the winning tribe which usually amounts to some type of food like an Outback Steakhouse meal or equipment like tarps to protect themselves from rain. Sometimes the rewards are more personal and can be letters, visits, or videos from loved ones – keeping the emotional motivation strong throughout the show. Immunity Challenges, on the other hand, keep the tribe safe from the oh so dreaded Tribal Council. The tribe that loses the Immunity Challenge arrives at Tribal Council that night where they must cast secret votes to determine who from their tribe will be sent home and lose their chance at winning the $1 million. But, before then, the contestants are in store for an afternoon of full-blown manipulation and betrayal.

Before arriving at Tribal Council the castaways begin to discuss who they’re going to vote out while they’re back at camp and this is when we see the formation, as well as the destruction, of alliances. Starting the very first day, the castaways begin to form different alliances within their tribes to ensure their safety at Tribal Council, but slowly these alliances dwindle and the castaways become blindsided left and right, one after another. There’s almost always a mastermind that spearheads these blindsides and acts as a sort of puppeteer, completely manipulating the rest of the castaways in the tribe. Day by day the game becomes more intense and more serious, and eventually the two tribes combine to become one – and this is when it gets good, really really good.

When the tribes combine, everyone is placed in the same campsite rather than two separate ones, and the paranoia truly begins to set in, not only with the players, but with the audience as well. Typically, those in the minority (meaning those that aren’t in the main alliance) get voted off one by one, BUT every once in a while plans to vote certain people off fail due to Immunity Idols that individual contestants can win during the challenges, and Hidden Immunity Idols that contestants can find buried around camp. So, at this point, the castaways really begin to scramble to either join the main alliance or to find hidden immunity idols, all of which will protect them and their chances at becoming the Sole Survivor. There have been instances when contestants have straight up stolen immunity idols from other contestants, displaying completely ruthless tactics ensuring to protect themselves over the others. Not everyone’s this sneaky or evil, though. There’s always the nice guy or girl that everyone falls in love with, but the less conniving you are the lower your chances are of making it to the end. This game of deceit, blindsiding, and backstabbing continues throughout 39 days, and at the end the final three plead their case as to why they should win $1 million in front of the jury (made up of previously eliminated contestants) at the final Tribal Council. The winner, chosen by the jury, is then revealed at a live show after the final episode.

So far, I have basically categorized Survivor as a deceitful game filled with suffering and betrayal. Which is true, but it’s actually so much more complex than that. First of all, why would anyone want to watch people suffer both physically and mentally for 45 minutes nonstop? Strangely enough, even though the game is real, with real people in a real place, it does have some fantastical elements to it that keep drawing you in. It’s almost like a fairy tale, not the happy, magical Disney-like fairy tales, but more like the original stories of survival that are filled with both good and evil, and an overwhelming sense of justice.

Survivor is exactly that: a tale of survival. Fairy tales are just the same. Both manage to tap into our greatest fear as humans: complete isolation. There truly is no greater threat in life than the thought of being completely deserted. When contestants enter the game of Survivor, they leave behind their families, their jobs, their friends, and their lives. They basically have to start from scratch as they develop a new shelter and are surrounded by strangers that they have to befriend. If you’re in the minority alliance, without any way of saving yourself, even though you’re still physically surrounded by people, you have no one to fight for you or to fight with you. Isolation doesn’t have to be just physical, but it can also be completely mental and emotional, and Survivor is an expert at creating that mental isolation within the contestants – you never know who’s going to flip and blindside you or who’s going to leave next, so you’re truly on your own and left to fend for yourself. You cannot trust anyone because the second you start to, you’re out of the game. We see this same fear of isolation appear in various fairy tales throughout time. In stories like Rapunzel, the titular character is essentially abandoned by her parents when they choose food over her. She’s just a baby when this happens, so she doesn’t necessarily know, but still, as a child reading this story imagine the fear that sets at the thought of your parents, the people meant to protect you for the rest of eternity, willingly abandoning you. Hansel and Gretel shares a similar sentiment when the father chooses his wife over his children and leaves them in the middle of a forest to starve. What these children must do is find a way to survive these evils, just like the contestants on Survivor and just like we do in daily life.

The contestants’ ability to navigate through these evils of starvation, isolation, and paranoia makes it easy to forget that they are just normal people, like us, that come from normal places with different backgrounds. As I watched those two seasons of the show on Netflix, I found myself looking up to the castaways as if they were heroes completing these seemingly impossible tasks. Former Survivor contestant, Stephen Fishbach even agrees his capabilities were beyond his comprehension: “My second season, as my body gave out in the Cambodian monsoon, I saw that even when I was at my lowest, still by force of will I could continue forward.” Personally, I know I wouldn’t survive a day on Survivor! No food or shelter for over a month? Yeah, no thanks, I’d rather just watch from the comfort of my own home, snacking on some popcorn. But as I’m sitting on my couch, I watch these contestants rise above us mortals as they live in this fantasy land of survival and I find myself transported into the wondrous and foreign world that is Survivor. I find myself feeling for the contestants, imagining what it would be like to be them, thanking the universe that I’m not one of them, but still, I begin to identify with the characters in the same way a child would with fairy tale characters. In these tales there’s usually two main character types: the one that gives into despair, that sits there crying until a magical helper arrives to guide them, and the one that takes matters into their own hands and attempts to escape their terrible fate. The contestants in Survivor are no different. The ones that go hunting for hidden immunity idols without any clues are typically the ones that make it far in the game while the ones who sit around and do nothing are voted off fairly quickly. What fairy tales and Survivor both do is expose human behavior – both the good and the bad that we carry. They present characters that are kind and contrast them with the evil character that, from my perspective, must be avenged. Survivor: Heroes vs. Villains is a perfect example of this.

Throughout the Heroes vs. Villains season, we see Russell Hantz become the mastermind puppeteer of the game. He tricks people left and right to give him immunity idols and manages to blindside some of the most beloved Survivor contestants of all time. He’s the villain of the season, and he makes it to the final three. The other two castaways in the final three are Parvati Shallow and Sandra Diaz-Twine, two women that may not have been the nicest of people through the entirety of the game, but were nowhere near as betraying and disloyal as Russell. When the jury votes for the winner, absolutely no one casts a vote for Russell, and for the second time in a row, he loses the $1 million. While the villain doesn’t always lose on Survivor and the “good guy” or “not fully the bad guy” sometimes wins, there’s an overwhelming feeling of justice that arises when the villain does lose because, to me at least, rewarding the villain just seems wrong. In The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettleheim notes that “children are innocent and love justice, while most of us [adults] are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.” I find there to be some truth to this statement. The beauty of Survivor, or at least in my own experience, is that it transports you back into a mesmerized, childlike state, engulfed in those feelings of unmanageable chaos that we experience when we’re young and unaware of how to control or work through our emotions. But the villains of the show, they’re like the adults in the real world and in fairy tales. They prefer mercy over justice and allow their wickedness to guide them and foster their desire to win. So, yes, it’s upsetting to those of us that tap into our childlike states while we watch the show when the villain wins because we feel a sense of loss and a lack of justice. But, I think I keep going back to the show because of those instances when the heroes do win, validating my hopes and feelings, and creating a sense of comfort. At the end of the day, Survivor follows the same process as many fairy tales: fantasy, recovery, escape, and consolation. The contestants are placed in this survival fantasy island in Fiji, they have to recover from feelings of complete despair, they have to escape from the villains’ traps, and in the end there’s typically a consolation of justice being achieved. But what if the villain wins? How does consolation present itself then?

Here’s the thing… it all ends, eventually. IT ENDS. Even if the villain wins, the game has to end. That’s our ultimate consolation. That’s my consolation. That’s my comfort. That’s why I keep coming back to Survivor and the reason why I can live peacefully with my obsession. I know that the game doesn’t last forever and I realize it’s not me who has to physically experience the game. The fact that the game ends and that a new season starts soon after also gives me hope that the nice guy will beat the villain next time. I feel comfort in knowing that there’s another chance for good to beat evil. Rather than having to undergo those terrifying feelings of isolation and starvation, I can simply just live vicariously through the contestants. In fairy tales, children are consoled by the instances of justice – like Little Red killing the wolf and Cinderella’s step sisters getting their eyes pecked out by birds – but also by the fact that they’re transported back to reality once the story ends. They’re not the ones in the story, but they manage to identify with the characters and the storyline by living vicariously through them to work out their chaos and fears. Children, through fairy tales, and I, through watching Survivor, can finally come to realize that we aren’t actually deserted and won’t be anytime soon, because oftentimes there’s going to be a happy ending with these characters managing to make it one more day. At the end of the day, that’s all we can do too: survive.

COVID-19 has completely changed our reality, and the current world is unrecognizable. One of the largest problems that my family and I have personally faced is dealing with childcare. My brothers both have children, and they and their wives work full-time. One of my brothers is a pediatrician; luckily, he has been able to live at home despite working in a hospital, and his wife is a teacher, so was able to spend time with their 1-year-old son during her summer vacation when the pandemic first hit and daycares shut down. My other brother and his wife, however, work full-time on the phones for a broker, and the pandemic did not change that. They were forced to give their 18-month-old daughter to her grandparents for a few months, a transition that was traumatic due to the unknown duration and the physical distance between them: my brother lives in Nebraska, his in-laws live in Colorado.

Watching my brothers struggle with childcare, and personally stepping in as a nanny for a close family friend because of childcare issues, I realized how many people were being affected in this way during the pandemic. After reading tales such as “Hansel and Gretel” and “Rapunzel” that feature child abandonment and isolation, I was immediately drawn to the idea of using these stories to analyze and cope with the current situation because fairy tales offer hope when reality seems bleak, and we desperately need hope during this time. Whether your family has personally dealt with the problems of finding childcare during this time or if you know someone who has, almost everyone can relate to the anxiety it causes. People may be experiencing wish fatigue, but fairy tales remind us that wishing is never a waste of time. There is always the possibility of a “happy ending,” and these tales provide hope that the current generation of children will survive this pandemic with new resolve and maturity, rather than trauma, as many parents fear.

The year 2020 has been anything but a fairy tale. It began with fires that devastated Australia, but that event was quickly overshadowed by the spread of COVID-19, a disease that single-handedly changed lives across the world. Businesses shut down, Zoom University became the only option for higher-education, and masks appeared as the new (mandatory) fashion trend. Add one of the most divisive U.S. presidential elections in recent history and the unearthing of persisting blatant racism, and you get what 2020 has become: a year filled with fear, tension, and hopelessness. How could this be anything like a fairy tale?

Fairy tales are full of princesses, princes, and happy endings. The Disney store beckons, walls overflowing with sparkling dresses and accessories. That is a fairy tale. There is no extensive violence, no uncertainty threatening to drive the characters to insanity. Or is there? Disney sanitized tales into forms often unrecognizable from their oral counterparts, but these versions are the ones most people are familiar with. Disney removed much of the blood and gore in “Cinderella,” such as when her stepsisters cut off parts of their feet in order to fit into the glass slipper, and rejected versions of “Snow White” that depict the prince as a necrophiliac or force the evil queen to dance in red-hot shoes until she dies at Snow White’s wedding. These details were deemed “unfit” for children, so they did not make the final cut for Disney’s renditions.

Disney’s intentions may have been rooted in a place of genuine concern towards preserving the innocence of children, but the current state of the world demands the true nature of these tales. Our reality is grim, so while oversaturated films where the biggest problems are jealousy or extra chores provide escapism, we cannot relate to their eventual happy ending. It is not unacceptable to dress up in a sparkly blue dress, don a blonde wig, and imagine a fairy godmother who will magically appear and grant our wishes; it is a mistake, however, to gloss over the true trauma in the story. We need to be reminded of the horrible occurrences in fairy tales because they reinstate hope. If fairy tale characters can endure vengeful fairies, poisoned apples, or wolves with an appetite for young girls, we can surely face our reality.

That reality, however, can be daunting. As COVID-19 became more of a threat, normal societal behaviors were placed on hold as people sheltered at home, terrified to go outside. Social interactions became a thing of the past, and everyone put on their armor in the shape of a face mask. Forget the knight in shining armor. He can no longer save us. Life suddenly seemed to mirror a dystopian film or novel and a sense of detachment arose. Going to the grocery store became an act of bravery. Will there be toilet paper today? Will it be worth the risk? Working parents, however, faced one of the most pressing problems: how to work and still take care of their children, without being forced to abandon them.

My brother and his wife abandoned their child. How could they do this to my sweet, cherub-faced niece? They did not leave her on the streets and had every intention of retrieving her, but the pandemic created circumstances where they could no longer take care of her. As COVID-19 became a more dire issue, my brother and his wife faced a terrifying prospect: their 18-month-old daughter could no longer go to daycare, and they both work full-time. With technology being what it is, a pandemic did not dispose of these responsibilities, but rather increased them; their workspace was now their home. Throw in three dogs, and there was no way to ensure that everyone had their needs met. Hectic was an understatement. One of them quitting their job was not an option because they had only just begun to make ends meet. Although daycare added an expense, it was still better financially than having a stay-at-home parent. The irony of this situation is evident; we work to pay for people to watch our children while we work.

With this fear looming down, they realized that they had to find a place for their daughter to go, even if that meant being separated from her for an extended period. This decision was not easy, but necessary given the ever-spreading pandemic. My sister-in-laws’ parents offered to take care of my niece for however long was needed, but they live in Colorado. My brother and his family live in Nebraska. Although this situation was not the typical case of abandonment, because both of her parents wanted to stay with her and she was going to a place where she would be loved, my niece was still forced to live away from her parents for a few months. She was also at an age when children are completely reliant upon and attached to their parents, making it more traumatic for all involved.

“Why are you crying?” I ask my mother. “She’s going to be damaged, I just know it,” my mother replies, as she calls my other brother, the pediatrician, for his opinion.

This decision, however, was a privilege in itself, despite the pain it caused their family. Many parents faced similar situations as cities imposed COVID-19 restrictions, especially those who belonged to the lower working class. They did not have the privilege of taking time off from work in order to care for their children because their jobs pay the bills and put food on the table. Daycare facilities and schools were relied on to provide childcare, but these services were taken away in a matter of days, and people scrambled to find alternatives. Where was the benevolent King to take care of his subjects? Is he just a figment of imagination?

Other families did not have the same support system as my brother and his family, had multiple children, or had essential jobs that took them out of the home. Working parents everywhere had to find ways to ensure that their children were safe, healthy, and still getting some semblance of an education, while also trying to pay the bills. Those who did not physically abandon their children emotionally abandoned them, leaving them unsupervised for most of the day while they worked. Zoom meetings are not conducive to parenting. Your boss can still see you.

This situation would not be out of place if written in a children’s story. It would be set in a different time period of course, “many years ago” or “once upon a time,” but the main components would still be there: fear, uncertainty, abandonment. Although the childhood abandonment instigated by a global pandemic may seem as far removed from a fairy tale as possible, one of the most common characteristics of any fairy tale is the departure of a character from the home, whether that be through death or a journey. Vladimir Propp sought to define this aspect, placing it as the first function in his list of thirty-one: absentation. Whether a parent dies or the hero departs on a quest, someone leaves the safety of home, venturing into the unknown. It is only through the trials and tribulations faced on their journey or in their grieving process, however, that the hero is able to achieve their happy ending.

We see this separation not just through children who are forced to leave their homes and live with others, but with parents who cannot come home for fear of infecting their children. Yes, the pandemic is real. Yes, it affects real people. Health-care workers must not only leave their children during the day, but many are unable to return home during this time. They live in pop-up campers in parking lots or hotel-like rooms provided by the hospital, apart from their spouses and children for months on end (Ellis). As the pandemic continues to drag on, they are forced to lengthen this period of separation indefinitely. Their isolation has no expiration date.

“Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair!” (Grimm, 125). Who needs a tower when you have a parking lot camper?

There is no amount of hair that will fix their predicament. There is no selfish witch keeping healthcare workers from their friends and families. They will not be rescued by a charming prince. Their captor is not tangible, and they must rely on society as a whole to take the necessary precautions to limit the spread of the virus so that they can soon return home to their families. Individual initiative helps, but only collective cooperation will halt this villain.

As the pandemic drags on, we must ask ourselves whether the idealized concept of a “happily ever after” will play out in reality, or whether our fragmented society is beyond repair. Is this cliché another Disney ploy? Buy into a happy ending while buying turkey legs in front of Sleeping Beauty’s Castle? Or is the idealized conclusion no longer confined to the pages of storybooks?

We can actually turn to classic fairy tales to help us answer these questions because of the similar circumstances threaded throughout many tales, such as “Hansel and Gretel.” This story is widely recognized as one of the quintessential fairy tales; people are familiar with the basic plot, even if they have not read it since childhood. Who could forget a gingerbread house? Writers have reimagined the tale throughout time, adapting it to fit more modern settings. The classic version, however, contains themes that align to our current situation in startlingly similar ways.

Hansel and Gretel are two children who are abandoned in the woods by their parents during a time of poverty and forced to face the elements. They are able to find their way back once in most iterations of the tale, but eventually succumb to their parent’s deception. After accepting their inevitable fate, their wanderings eventually lead them to a gingerbread house, where they eat their fill, only to learn that it belongs to a cannibalistic witch. A sugar crash is no longer their biggest problem. Luckily for them, they use cunning and trickery to escape, captivating all who hear their story by the fantastic image of an edible house and their ingenuity.

The tale has roots in the famine that devastated Europe during the 1300s; during this time, parents actually abandoned their children in forests or churches because they could no longer afford to feed them (Campbell, 0:57-1:05). Hansel and Gretel’s parents’ decision to leave their children reflects this time period because they are motivated by their financial insecurity and hunger. Their mother berates her husband, claiming that if they do not abandon their children, “[t]hen all four of [them] will end up starving to death. [He] might as well start sawing the boards for [their] coffins” (Tatar, 236). Hansel and Gretel are abandoned because of their family’s intense hunger and the way it affects each family member. There are no motherly tendencies. The mother reverts to base, primal instincts, saving herself without thinking of her children. She is willing to coerce her husband into giving up the children in order to save herself. It is never the man’s fault, after all. He would have been innocent if not for his wicked wife. No matter who receives the blame, we see the strain that financial difficulties can put on a family, a concept that is being echoed by the current state of the world.

Hansel and Gretel’s parents ignore the needs of their children in order to fulfill their own needs, but the motivating financial insecurity and resulting hunger resonates with parents during the pandemic. Grocery stores initially became barren as people flocked to stock up on what they deemed as necessities. Goodbye toilet paper, goodbye flour. Everyone became a baker during quarantine.

When food disappeared from shelves, more pressure was put on parents to provide security for their children, despite the struggles they were already facing. There was also a new fear of going hungry; families that usually did not have to worry about food faced new difficulties. Food became a main focus and induced stress, a trend similar to the famines that inspired “Hansel and Gretel.”

Food scarcity and financial anxiety change people’s priorities because they have a large impact on one’s overall lifestyle, something many are loath to give up or alter. The word “hangry” was coined for a reason. As Bruno Bettelheim notes, “poverty and deprivation do not improve man’s character, but rather make him more selfish, less sensitive to the suffering of others, and thus prone to embark on evil deeds” (159). Leaving a child unsupervised because you have to work does not constitute an evil deed, but it does show a lack of attention that normally would not occur to the same extent. Parents place great emphasis on taking care of their children, but when other, more base anxieties arise towards food or money, the latter takes precedence.

We also see a similarity in the struggles the children face once the parents abandon them. Modern children are not given to a cannibalistic witch, but there is still an element of danger. Giving a child to someone else, even if there are no other viable options, puts both the child and caregiver at risk. There is no way to ensure that the mere transfer of the child will not cause someone to become sick, nor is there a way to ensure that the other people are following the protocols you have set for yourself and your family. Every decision is laced with anxiety. The witch poses a threat because of her cannibalistic tendencies, but COVID-19 has made everyone a threat. This disease is a silent and stealthy killer. It is more terrifying than a villain in a fairy tale because it cannot be seen or easily identified in most cases. There is no dragon to slay or witch to escape, only the crippling fear of the unknown.

The relationship between “Hansel and Gretel” and the current reality has never been more important. Parents may balk at the idea of giving their child up, even if it is to a close family friend, but this tale provides some comfort because the children end up victorious. A happy ending, despite the trauma. The witch poses a threat to the children, but they use their wit to escape her clutches, a parallel we can hopefully identify as time passes during the pandemic. From Hansel’s idea to convince the witch that he is not yet fat enough to eat by “stick[ing] a little bone out,” to Gretel’s insistence that the witch must show her how to climb into the oven, both children demonstrate a level of cunning in order to secure their escape (Tatar, 240).

Their ingenuity allows them to secure their future. The children of today must also demonstrate a similar adaptability in order to persist despite their adverse circumstances. While there is no expectation that an 18-month-old child like my niece will be able to escape COVID-19, or discover a way to create a vaccine that allows society to resume normal activities in some capacity, there is hope that their resourcefulness will allow them to overcome the hurdles they are facing in some of the most formative years of their lives. They will not be damaged by the decisions their parents are forced to make, but will persevere to reach their “happily ever after” eventually.

Hansel and Gretel only return home after crossing a stream, a detail of great significance. This trek signals their transcendence past childhood and complete dependence—if only puberty was this easy. Before they met the witch, they were dependent on their parents and each other. By crossing the stream one at a time, they undergo a “transition, and a new beginning on a higher level of existence…[and] arrive at the other shore as more mature children, ready to rely on their own intelligence and initiative to solve life’s problems” (Bettelheim, 164). Their period of separation from their parents allows them to transition into more developed beings. It does not traumatize them, but rather is an essential aspect of their maturation.

The idea that the eventual transcendence of Hansel and Gretel can be applied to our current situation highlights the wish many of us have that the trauma we are experiencing will be fruitful in some regard. The pandemic has altered our way of life fundamentally, and many feel powerless or out of control, so wishing for something better is natural. Wish fulfillment is a concept also popular in fairy tales; Cinderella wishes to go to the ball, and her fairy godmother provides—just get back before midnight, the ever important caveat. In the past months, however, modern society is experiencing a new phenomenon: wish fatigue.

At the start of the pandemic, wishing was all we did. We wished for things to return to the way they were pre-pandemic, at least in regards to face masks and social distancing. We wished to be reunited with friends and family in person instead of over a computer screen, and we wished for the things we once took for granted. As the months dragged on, however, our wishes became less frequent; this new way of life seems permanent and inescapable. Many, including my own family, began experiencing wish fatigue. Wishing seemed futile. Nothing was changing, so what was the point?

The extent of the wish fatigue we are experiencing now is unprecedented. It may seem pointless to read a fairy tale because of the lack of hope towards a possible happy ending, but this situation is what makes engaging with fairy tales even more important. They are not just a promise that things will get better, but a reminder always to wish for better things, even when they seem impossible. Remember Hansel and Gretel? The two children who were able to outsmart a cannibalistic witch and find their way back home through a forest? Nothing is impossible. The drastic conditions in fairy tales surpass even our grim reality, yet these characters do not give up their hope even after many years of suffering. We have suffered for less than a year, although it admittedly feels much longer. We cannot give in to the wish fatigue plaguing us because, in doing so, we forfeit our happy ending.

Fairy tales, such as “Hansel and Gretel,” do not provide a realistic reflection of the events occurring in the world, but they do provide a road map that allows us to understand how we can cope when presented with new horrors. A cannibalistic witch is a magical and purely fictional creature. A global pandemic that completely changes society, however, was also once unimaginable. Fairy tales allow us to understand that life will present unforeseen challenges, but that falling into despair will not solve anything. As daycare facilities remain closed, or even as they begin to open back up, parents will continue to be faced with the prospect of giving their child up for a time in order to provide for them in the future, or sending them to a place that could potentially expose them to the virus. Each family must make that decision based on their individual circumstances and situations, but it is important to think back to fairy tales that describe this type of abandonment, and the ultimate transcendence of the child into a grounded and content adult.

We desperately need hope in this time, and fairy tales provide it. No longer tales reserved solely for children, these simple yet profound stories allow us to perceive the world around us in a new way and gain insight into how best to navigate the rocky road ahead. We must believe future generations will persevere, and we must believe that wishing for better times is not a foolish endeavor. Without this belief, we will descend further into the chaos around us. We must fight the fatigue we feel and trust that society will overcome this adversity. We will get through this pandemic, and all it entails, with a little help from Hansel, Gretel, and our other friends who have already faced the unimaginable and returned unscathed and triumphant.

______________________________________________________

Works Cited

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment. Vintage Books, 1989.

Campbell, Jen, director. The True History of Hansel and Gretel, YouTube, 24 July 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VQ6xchEAQY.

Ellis, Emma Grey. “How Health Care Workers Avoid Bringing Covid-19 Home.” Wired, Conde Nast, 14 Apr. 2020, 8:00 am, www.wired.com/story/coronavirus-covid-19-health-care-workers-families/.

Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm. Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Grosset & Dunlap, 1963.

Tatar, Maria, editor. The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism. 2nd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Mrs. Lee, my kindergarten teacher, was not my first introduction to the power of staying on task, finishing what I start, and not giving up. Disney stories were not the first to show me that anything was possible. If children’s storybooks and fairy tales are the amalgamation of magic, marvel, and meaning, then my origin, my bloodline, is the quintessential Disney storybook. The lessons and experiences from my parents’ life anecdotes, tales, accounts, and narratives, have revealed to me the story of my ancestors, my family, and my community. This repertoire illustrates the magic and marvel found in growing up dirt poor in a pueblo in Mexico and making the most of living in the barrios of East LA.

Similar to the story of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” I too share humble beginnings and have been entrusted with a great responsibility. Like Jack, my responsibility is to metaphorically take the “magic beans” my parents have entrusted me with and see to it that they grow into something special. It is through the lens of my parents’ lives — their struggles, sacrifices, setbacks, triumphs, and optimism — that has had the greatest impact on the person I am today. These “magic beans” have sprouted into a magical beanstalk that lies deep within me: spurring imagination, engendering hope, and brimming with optimism. My beanstalk grows confidently, exploring a world full of possibilities, and knows only the very top of the sky as its ceiling.

“Papá you actually lived in a house made of dirt without electricity, gas, and indoor plumbing?”

As a little girl, my parents’ stories were captivating and unbelievable; I was unable to fathom a reality so different from my own. “Papá, you actually lived in a house made of dirt without electricity, gas, and indoor plumbing?” I asked incredulously. I would paint mental images of my parents’ pueblos and would commonly contrast the quotidian events of my childhood with theirs. My dad would share with me his experiences living through the 1968 Chicano blowouts as a teenager at Roosevelt High School and of supporting Cesar Chavez and the farmworker boycotts. I often found myself wondering what I would have done had I been there. My mom has talked about all the responsibilities she had as a child. By the age of 10 she knew how to buy groceries, wash clothes at the river banks, and how to make tortillas. My parents’ stories left me in awe and wonderment and etched powerful and lasting images in my fertile and imaginative mind.

Slowly, I’ve pieced together my dad’s arduous journey: from going shoeless to shining shoes, from being disparaged for not speaking English in grade school to obtaining a college degree. In doing so, I gained a deeper appreciation of what it means to not give up and to always give it your best; to “echarle ganas.” “Echarle ganas”, the essence of giving it your all, is as deep-rooted and integral to the Mexican culture as balance and harmony is to the Chinese culture. This imperative phrase has since become much more than a motto. It is my mindset, my heartbeat, and my cultural battle cry as I aim high and give life my best shot.

Mija, always try to keep it simple, but reach for a deeper understanding of things”

As I mature, my understanding and appreciation of my parents’ experiences has only grown and intensified; filling me with a sense of wonderment and inciting gratefulness, a strong sense of self-awareness, identity, and pride. “Mija, always try to keep it simple, but reach for a deeper understanding of things,” my papá frequently advises me. I have put this into practice and it has helped me gain a deeper and more profound understanding of my culture, heritage, and myself. This mindset has also assisted me in gaining a broader, deeper, and more nuanced understanding of the realities and meaning found in the stories we have undertaken in this class.

I planted my “magic beans” in fertile ground.

As I take this time to reflect on my own story, I feel blessed to know that I planted my “magic beans” in fertile ground (unlike Jack who just threw them out the window). And we all know the reality, that good seeds will grow strong and healthy not by themselves, but only if they are nurtured and taken care of. As I continue to grow, I make sure to find time to engage in opportunities that help me stay connected and nurture my connection to my culture. For example, dancing as part of LMU’s Grupo Folklorico De LMU (as my dad did from 1973 to 1977), tutoring children who just immigrated from Mexico, and helping my family make tamales from scratch during the holidays.

My unique and evolving personal perspective — birthed, nuanced, and shaped by the influences of my immigrant roots, household, and community — is the stuff of Disney. My story is rooted deeply in overcoming the challenges that life puts in our path. Luckily, my parents instilled in me an “anything is possible” mentality and a “comeback can be stronger than your setback” attitude. A confidence dwells in knowing that my metaphorical “beanstalk” has Hispanic heritage, family, and community written all over it. It is a beanstalk growing, thriving, and blossoming, hopefully into something truly special.

Fairy tales are more than quirky stories told to children; they can be tools as well. Ever wondered why we read or tell them in the first place? One, because fairy tales are fun. They ignite our imaginations, fly us off to lands far from our realities, and allow us to root for the little guy that has a zero percent chance of defeating his enemy (even though, of course, he is victorious in the end). Two, because fairy tales have the power to instill lessons into the subconscious of an adolescent through that fun, where there is no danger of their fears and confusion coming into the life right before their eyes. Fairy tales are able to curb children’s “oedipal impulses,” as Bruno Bettelheim calls them, satisfy a child’s need for true justice (rather than the compassion we “adults” seek), and grapple with the somewhat irrational fears they may have of being actually devoured or abandoned by their own parents.

“Fairy tales do not tell children the dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.”

– G.K. Chesterton

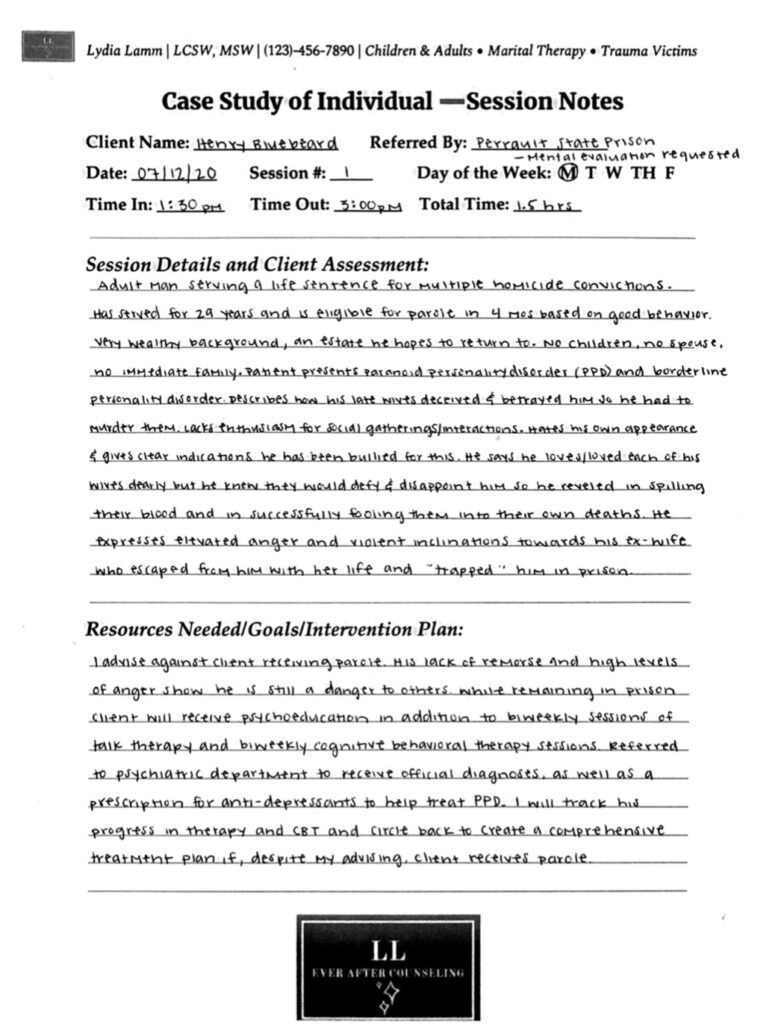

Fairy tales may be gruesome, countercultural, and absurd, but that is precisely what makes them into not only a new way for children to understand difficult-to-grasp concepts, but also a prescriptive medicine for even adults to begin healing from violent and traumatic events or to accept their mental situations in real life. Fairy tales grab reality, force it into a blender, and pour out a bubbling magical potion which resembles nothing of our own environment or understandings of the world. Because of this reorder of what we know to be true or real, a survivor of rape or sexual assault can begin reconstructing the narrative of their own traumatic event at a safe distance through the mystical land of Snow White or Sleeping Beauty, a victim of human trafficking may find solace in the familiarity of tales like Rapunzel or Beauty and the Beast, and an individual with paranoia, schizophrenia, or general anxiety disorder can learn they are not alone in their state-of-mind through tales such as Hansel and Gretel, Bluebeard, or even The Red Shoes. There are endless possibilities of how we can connect to ourselves, to our own identities, through the thousands of traditional fairy tales that exist, it is simply a matter of picking up and reading these tales or prescribing them to another as a form of therapy.

Welcome to Ever After Counseling. Take a moment and imagine that fairy tales did in fact consist of real people and that the events which unfold within them have taken place in our world today. Fairy tale characters would obviously need extensive psychiatric evaluations and treatment plans for the trauma they have either experienced, inflicted, or both. The following is a representation of four fairy tale characters who are referred to a social worker by various entities and of how they are evaluated, diagnosed, and potentially treated in light of their mental states, material and emotional resources, and the physical actions they have committed in their conditions.

(PLEASE disregard my mediocre photoshop skills, the images are for comedic effect.)

I’ve always been super passionate about makeup. To me, it’s an art and a way of expression that you get to wear on your face! For this project, I wanted to put my makeup skills to the test and create several looks inspired by different fairy tales. This definitely presented some challenges as I don’t have much practice with this style of makeup, but I had a lot of fun doing it!

I was first inspired to take on this project after learning that Ursula of Disney’s “The Little Mermaid” was actually inspired by a drag queen. I have always been impressed with drag makeup and fascinated by drag culture. After doing some research on the history and importance of drag, I decided to pay homage to Ursula and Divine, her inspiration, through a drag-inspired makeup look.

To create the purple base, I used my Urban Decay Naked Skin Concealer in the shade “Lavender” (which was sadly discontinued). I then set it and contoured with my Juvia’s Place Zulu palette (a high-quality, black-owned company I am obsessed with). I had never done a drag look, but I had so much fun creating this. It took 2-3 hours from beginning to end due to the precision (and having to make my entire face purple). This was by far my favorite look of this project, and easily one of my favorites of all time.

The next look I did was inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl.” I don’t have a very steady hand, so creating this much detail on such a small area was extremely difficult for me. My goal was to depict the girl looking at the flame from her match in front of a snowy brick wall. Overall I’m fairly satisfied with how this one turned out given that it does not play to my strengths.

For this look, I created the brick background using my Urban Decay Naked Smoky palette (discontinued). I created the snow and the base for the girl using my NYX White Liquid Liner. Lastly, I filled in the details with shades from my Violet Voss Bright Vibes palette. I think the concept I was going for comes through alright, although there is certainly room for improvement.

The next look I created was inspired by Angela Carter’s “The Tiger’s Bride.” I was inspired by her description of the mask that the tiger wore and the way that he removes it and reveals himself. I wanted to create a split look that showed both sides of the tiger’s persona. Carter described the mask as looking too perfect to be human, so I tried to create a completely smooth and blank slate.

To create the orange base, I used the Lime Crime Venus Neon palette (discontinued) and did the stripes with my Pat McGrath Labs Double-Sided Eyeliner (discontinued, but another wonderful black-owned brand worth checking out). To create the peeling effect, I used Ben Nye Liquid Latex, which I have only used a handful of times. It is definitely a little tricky to work with due to the irregular peeling and the knowledge that if it gets on your eyebrows/eyelashes it will rip them off. Fortunately, I did not run into any issues with this look. I was very happy with the finished product and felt like it demonstrated the duality of the tiger.

This next look was an absolute failure, but I felt like I had to include it with the others. I wanted to create a nature scene inspired by “Hansel and Gretel” and the candy house, but the look was not as cohesive and detailed as I hoped. I think I definitely bit off more than I could chew with this concept, but I tried not to get too discouraged.

The base of this look was done with the Urban Decay Naked Skin Color Correcting Fluid in the color “Green.” I then added detail primarily using the Anastasia Beverly Hills Lip Palette Vol. 1 (discontinued) and the Smashbox Cover Shot palette in “Bold.” Although I tried to create a solid base, the colors (especially the blue for the sky) went on very grey and patchy. I also didn’t have the best supplies to create something as detailed as I would have liked. I couldn’t wait to take this look off, especially since my face was covered in lipstick!

Following the catastrophe of the “Hansel and Gretel” look, I wanted to do something a little less detailed. For this look, I was inspired by the dress in Charles Perrault’s “Cinderella,” which is described as being made of the finest silver and gold, paired with beautiful jewels. Inspired by the shine of this dress, I created a glittery, glossy, glamorous look that reflects the colors and essence of Cinderella’s dress.

For this look, I did my regular face routine, but I added some extra highlighter from my Anastasia Beverly Hills Glow Kit in the shade “Sun Dipped.” For the gold eye, I used a pressed glitter from the Pinky Rose Cosmetics Hypnotize II palette and, for the silver eye, I used an Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics loose glitter (discontinued). To add extra shine, I tried something new and applied Milk Makeup Eye Vinyl (discontinued) over the glitter. I then placed rhinestones of the opposite color (I buy mine at Party City, I wouldn’t suggest that as they probably aren’t eye-safe) under my eyes. For a little extra glow I finished the look with my Fenty Beauty Gloss Bomb in the shade “Fenty Glow” (this is the most universally flattering lip gloss, also a luxurious black-owned brand with the most inclusive shade range on the market). I absolutely loved this look and I would probably wear it out for another occasion. I had a lot of fun experimenting with the eye gloss and I thought the effect was super cool.

More than anything, this project taught me patience. These looks took anywhere from 1-3 hours to complete and they forced me to put my makeup skills to the test. I loved being able to take concepts from the tales and bring them to life through cosmetics. This project allowed me to break out of my comfort zone and get creative during an otherwise stressful time, and I’m proud of the results.

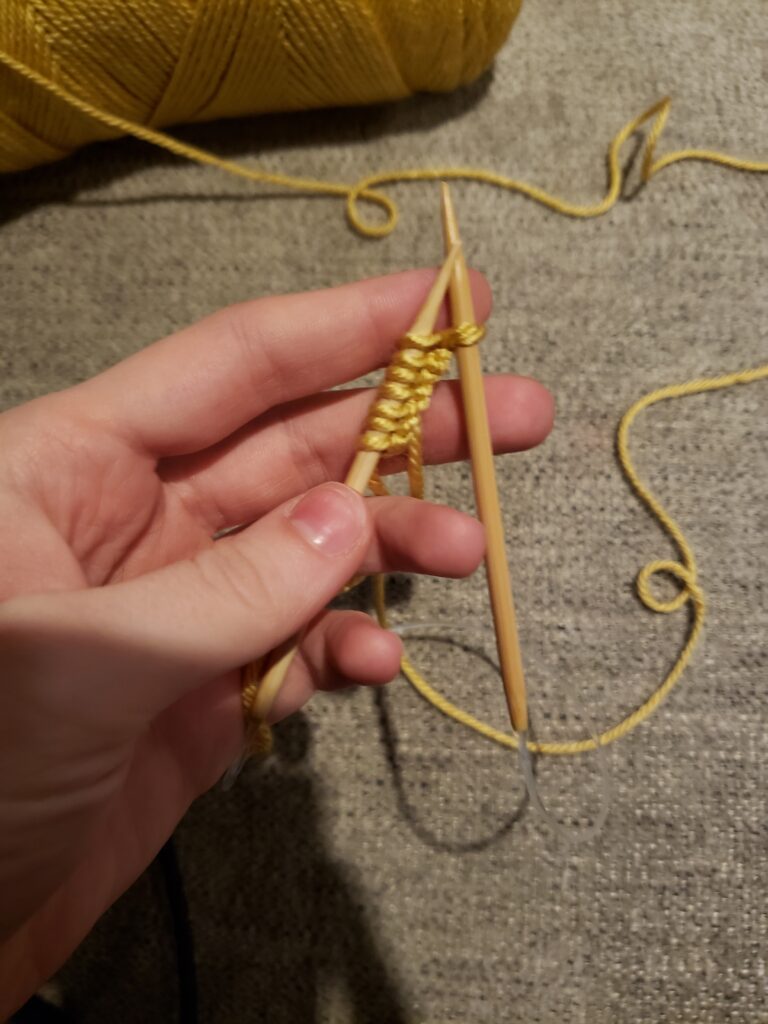

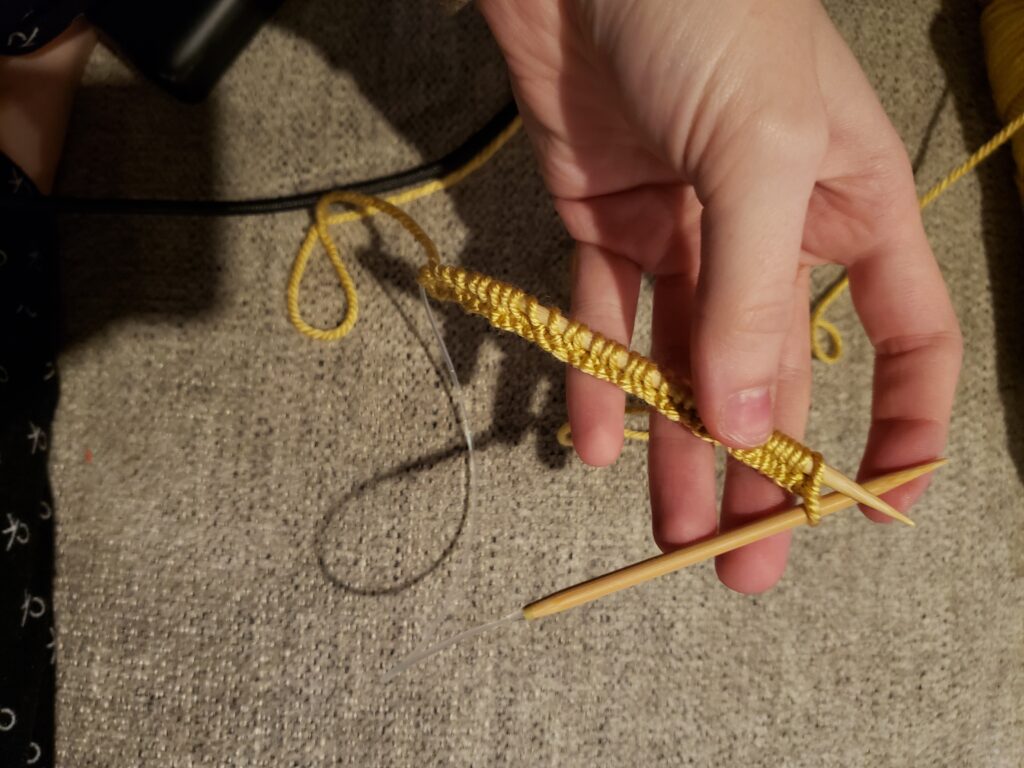

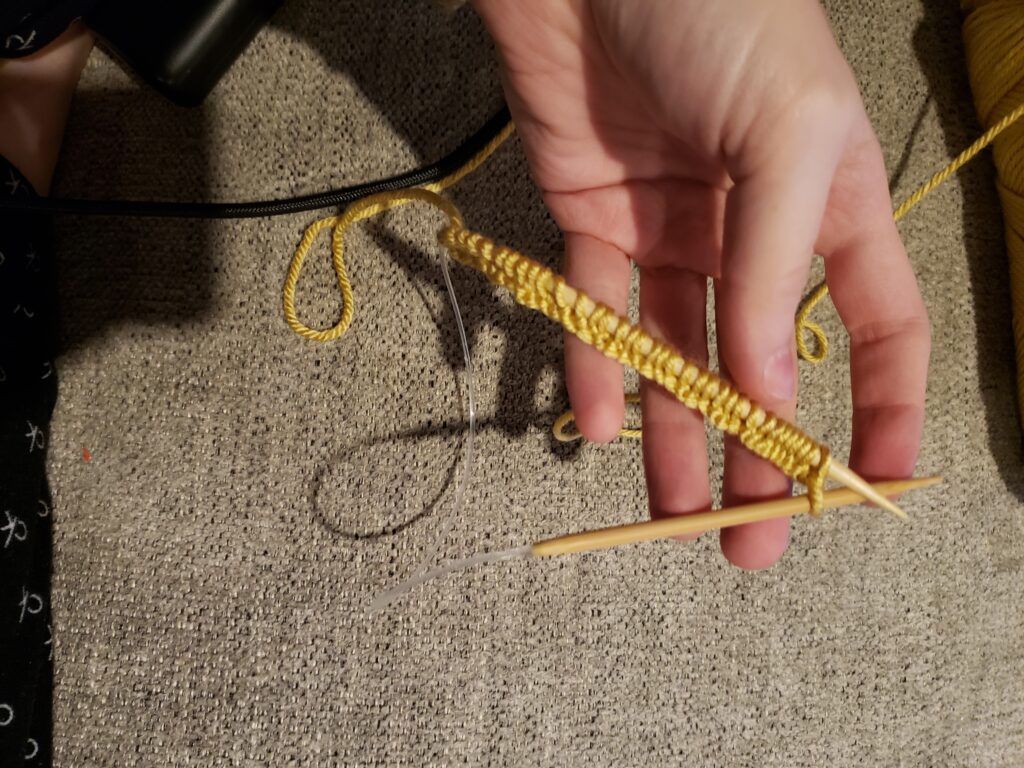

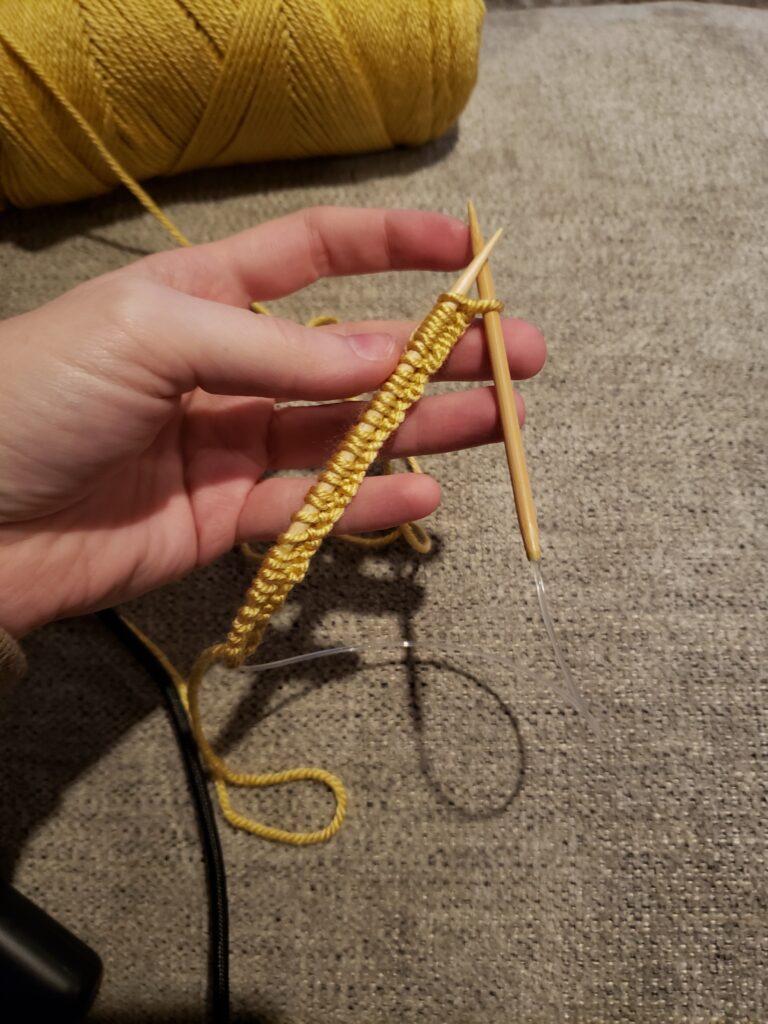

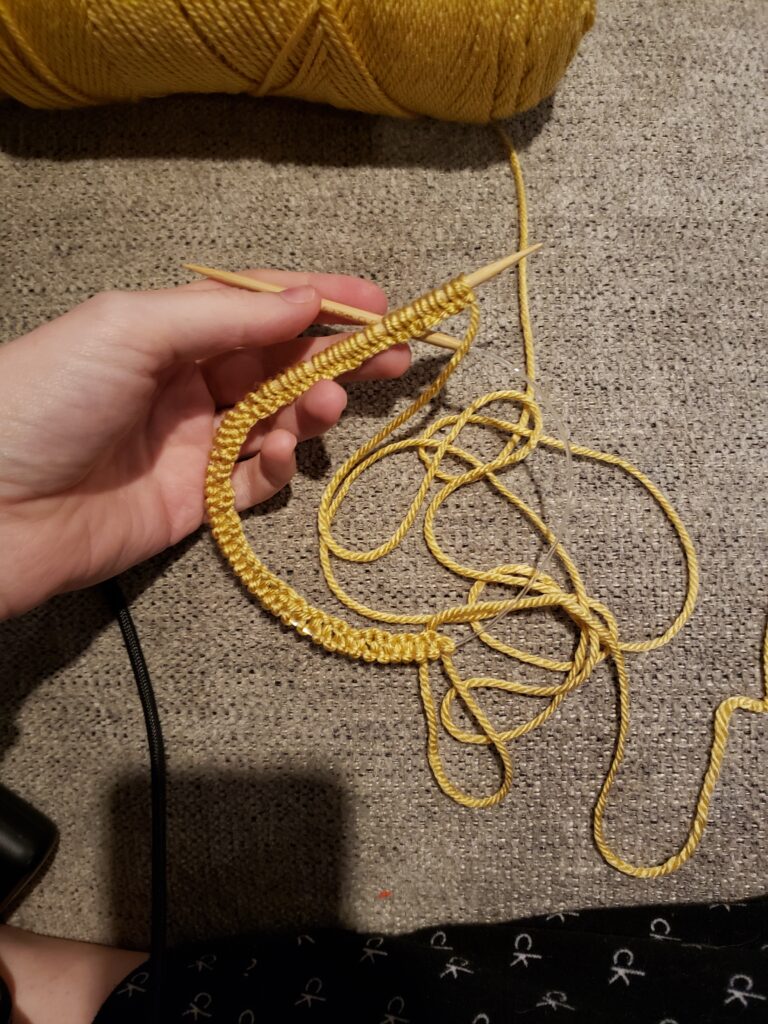

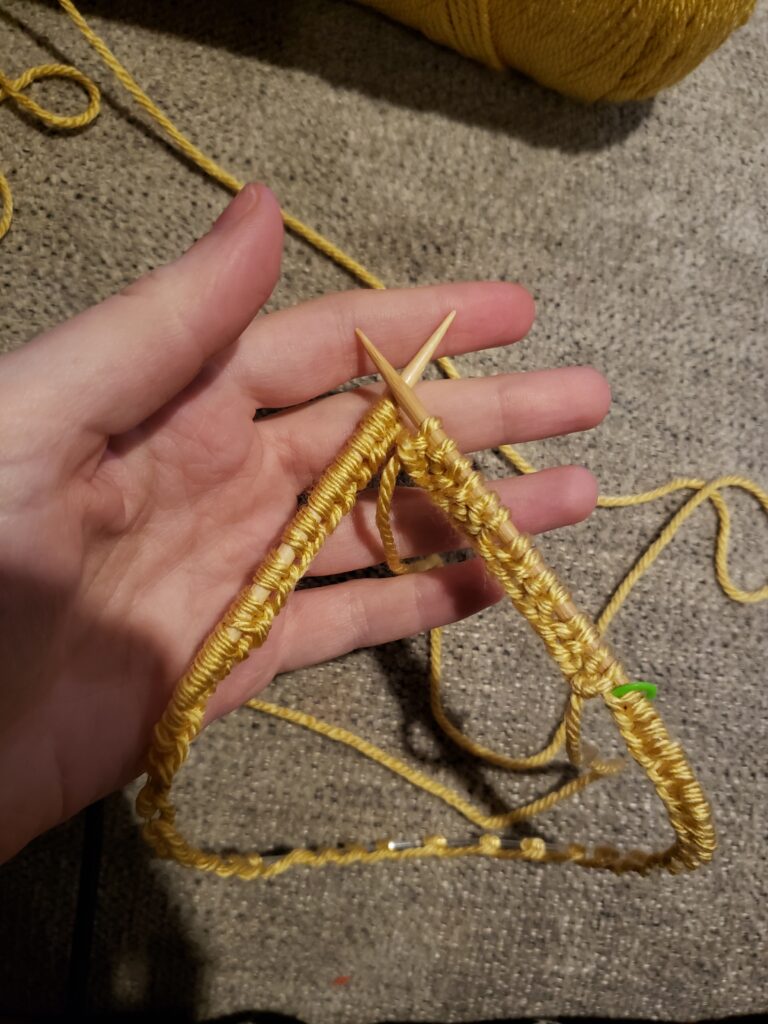

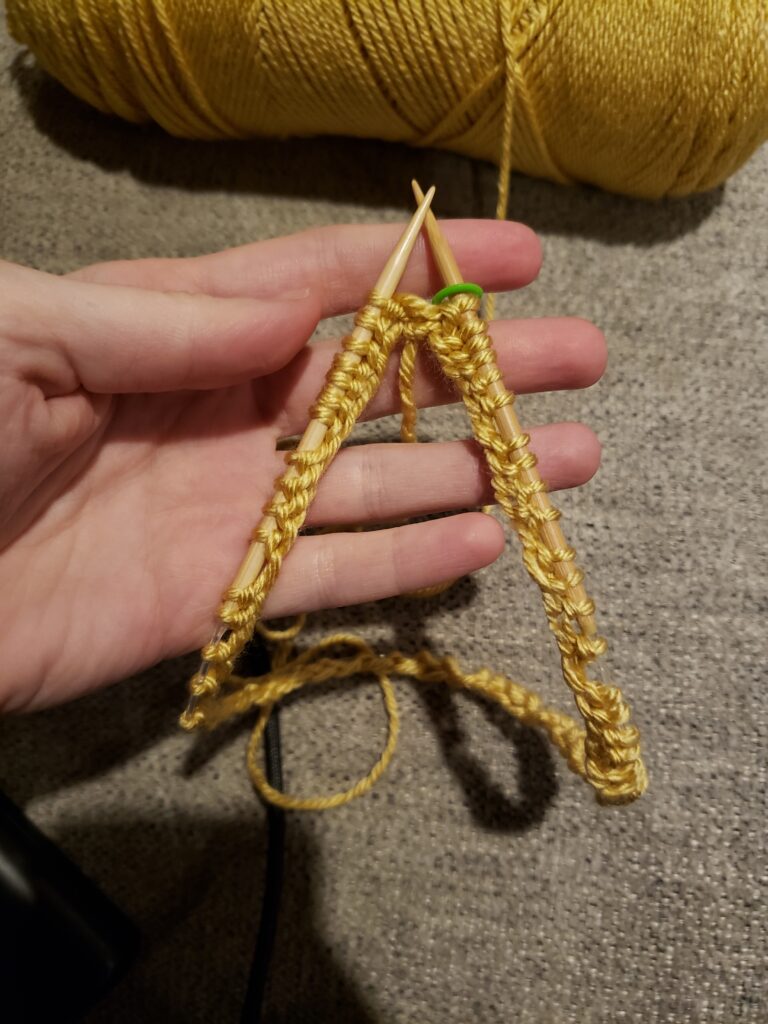

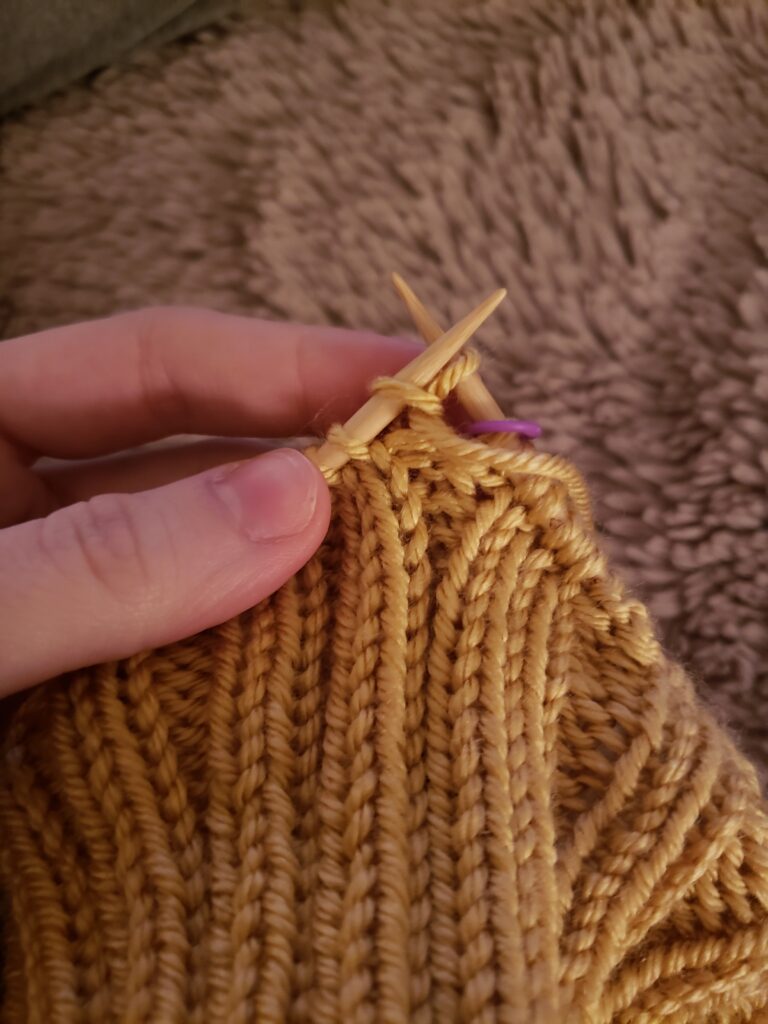

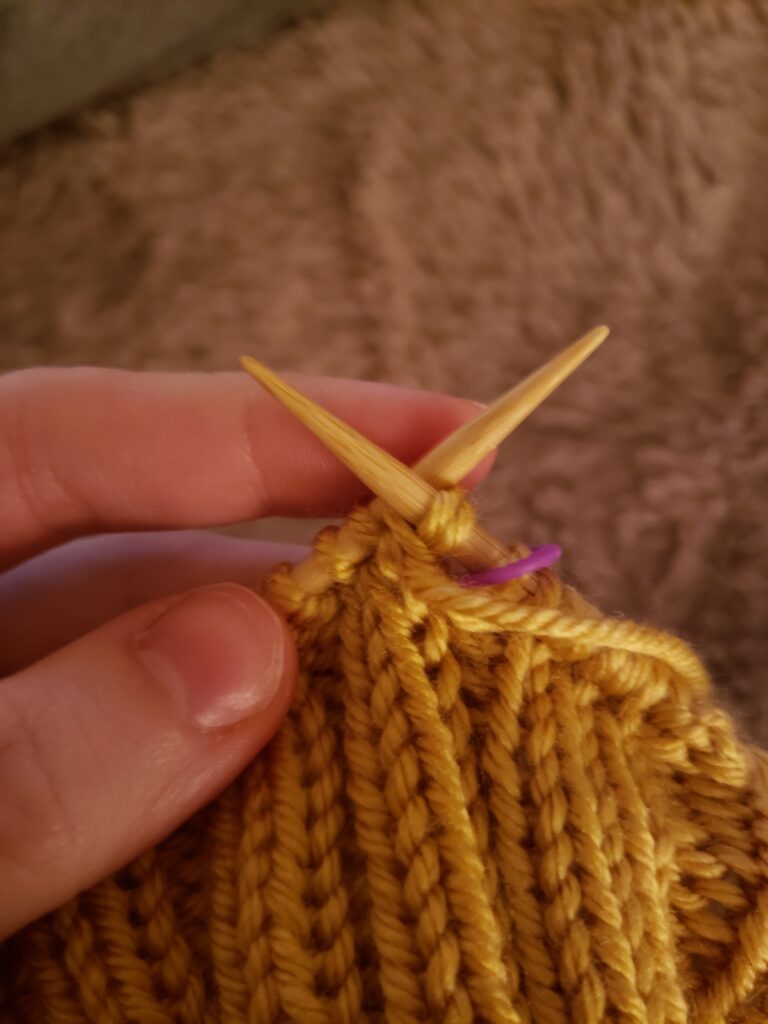

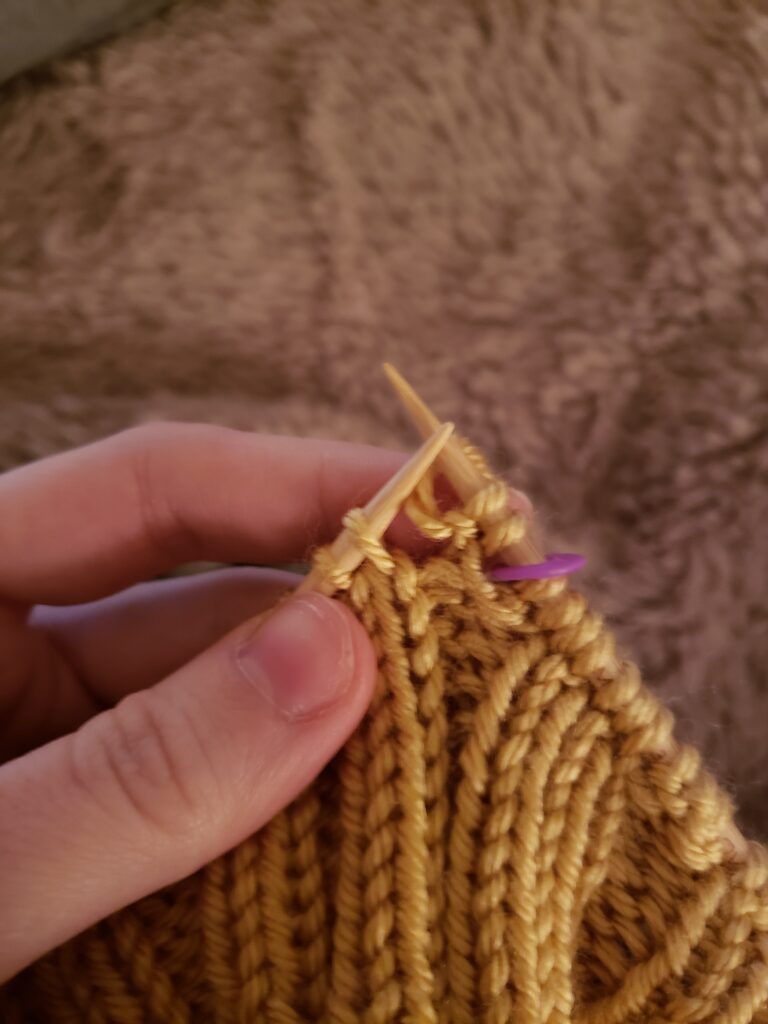

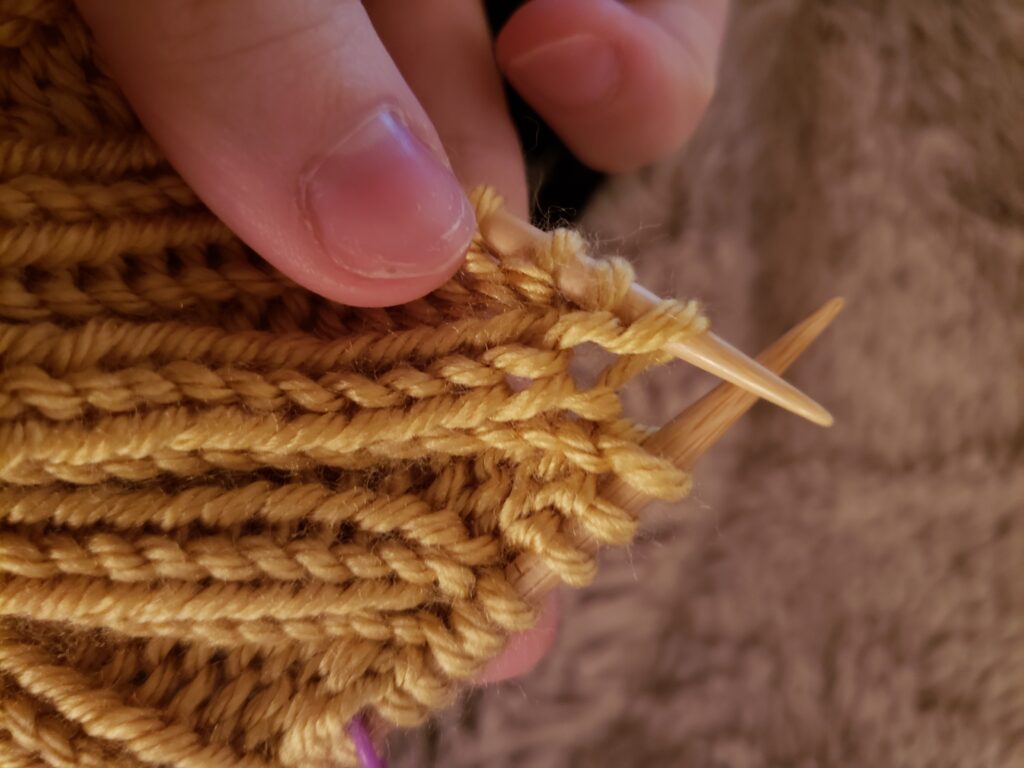

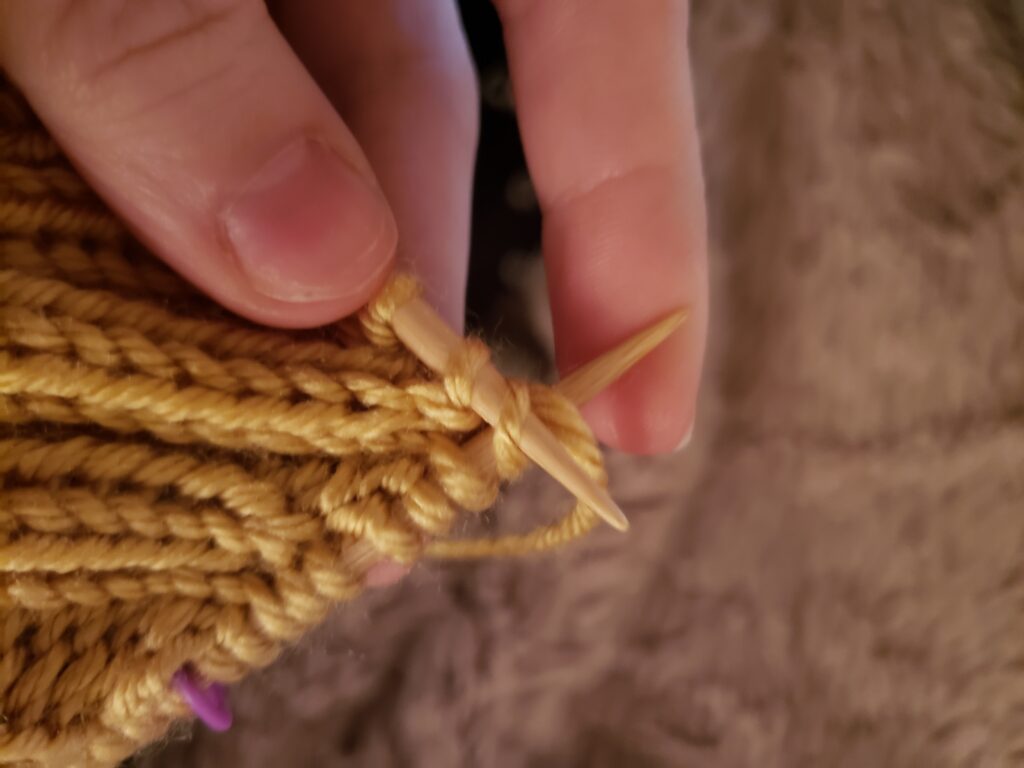

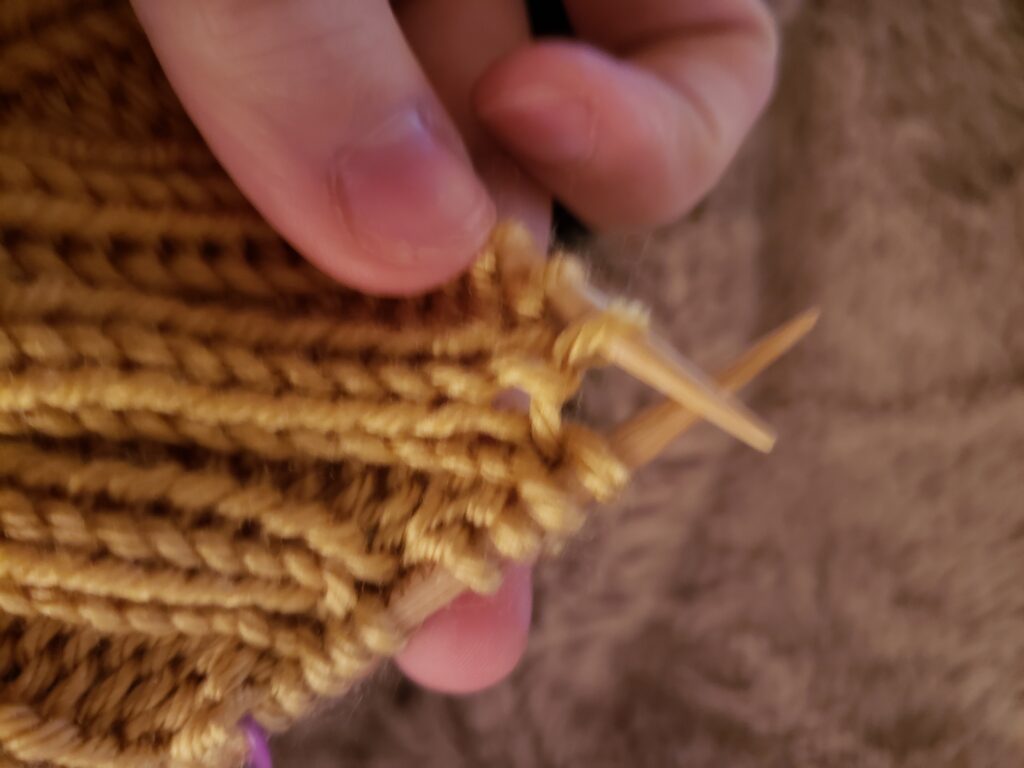

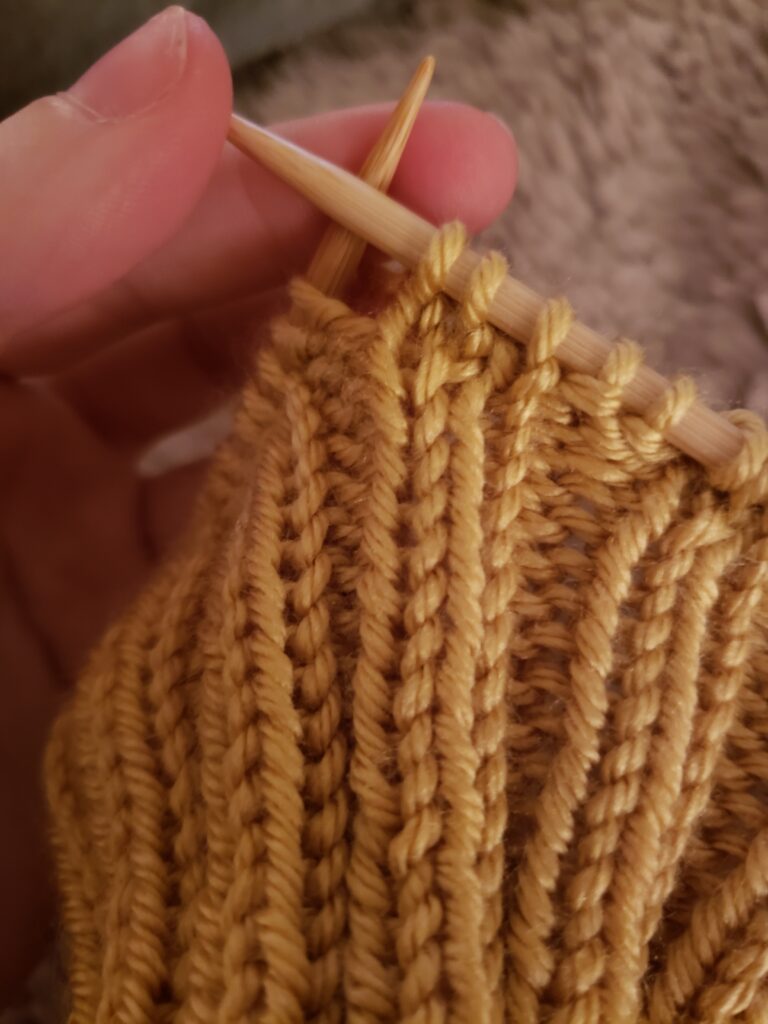

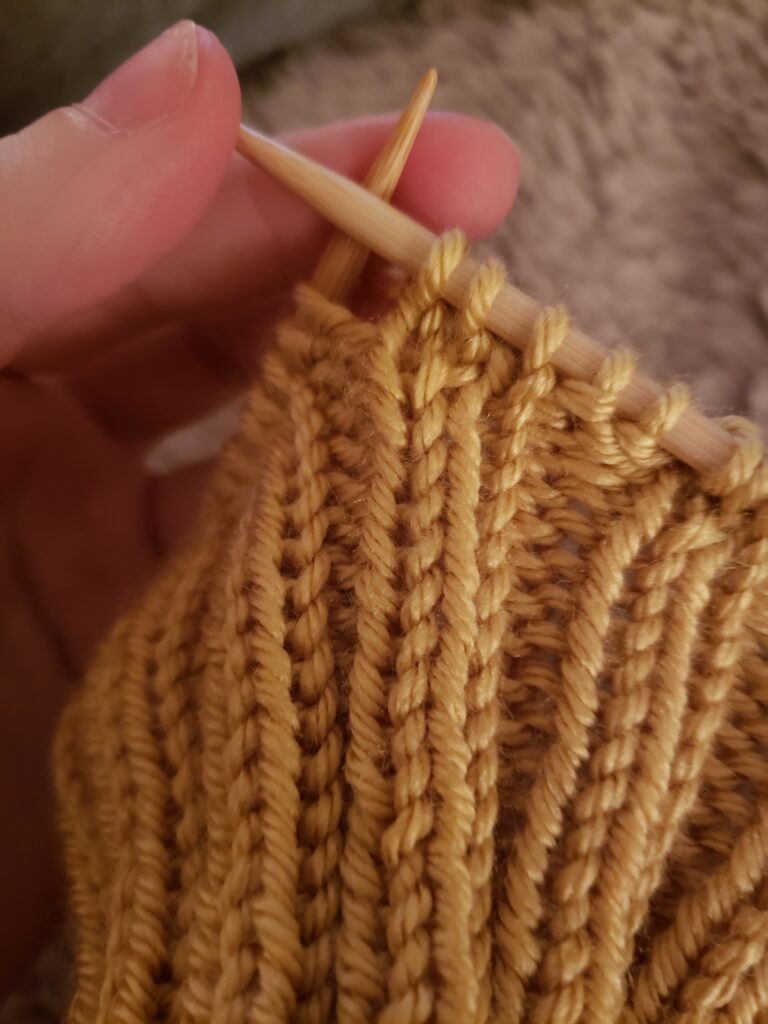

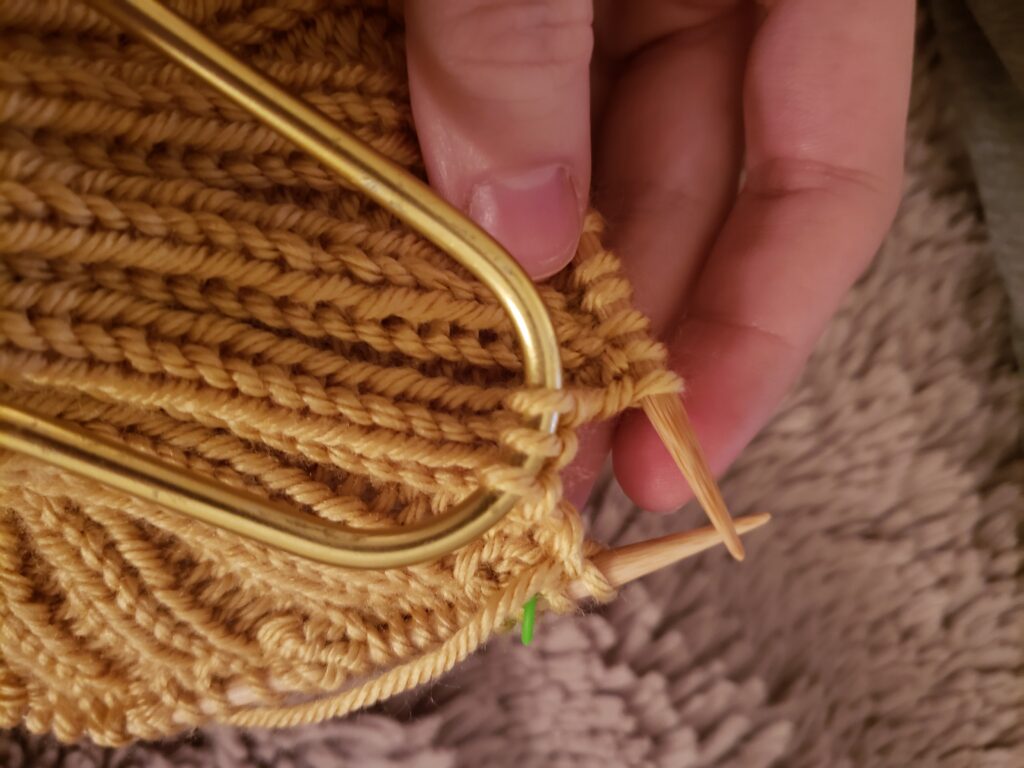

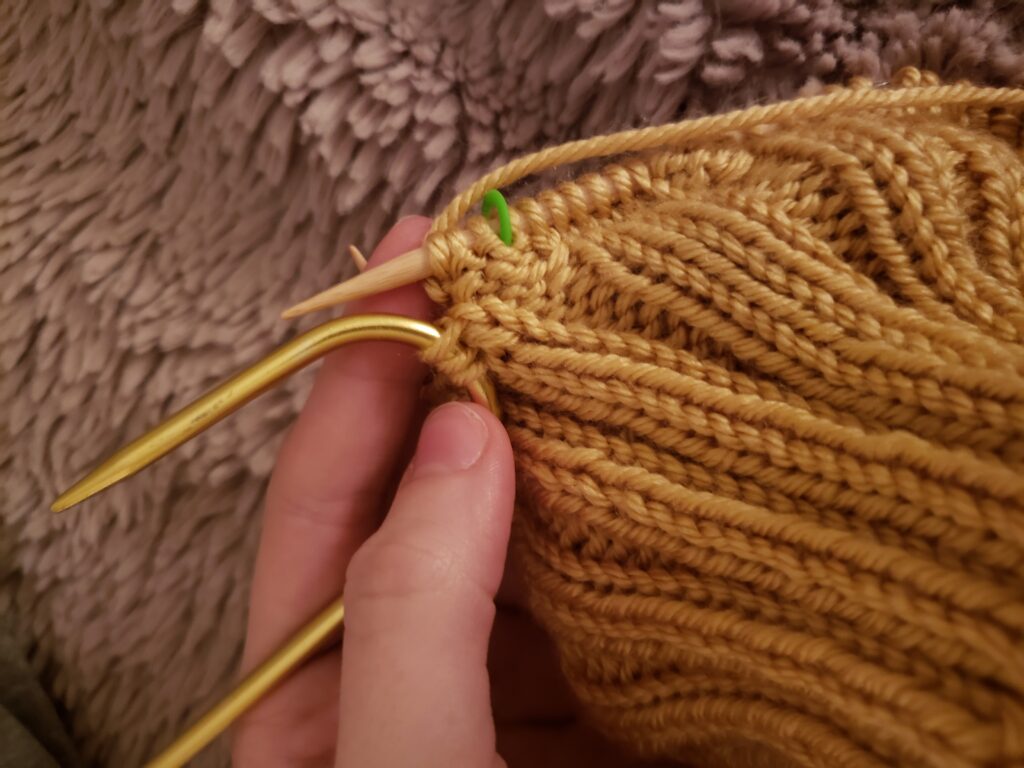

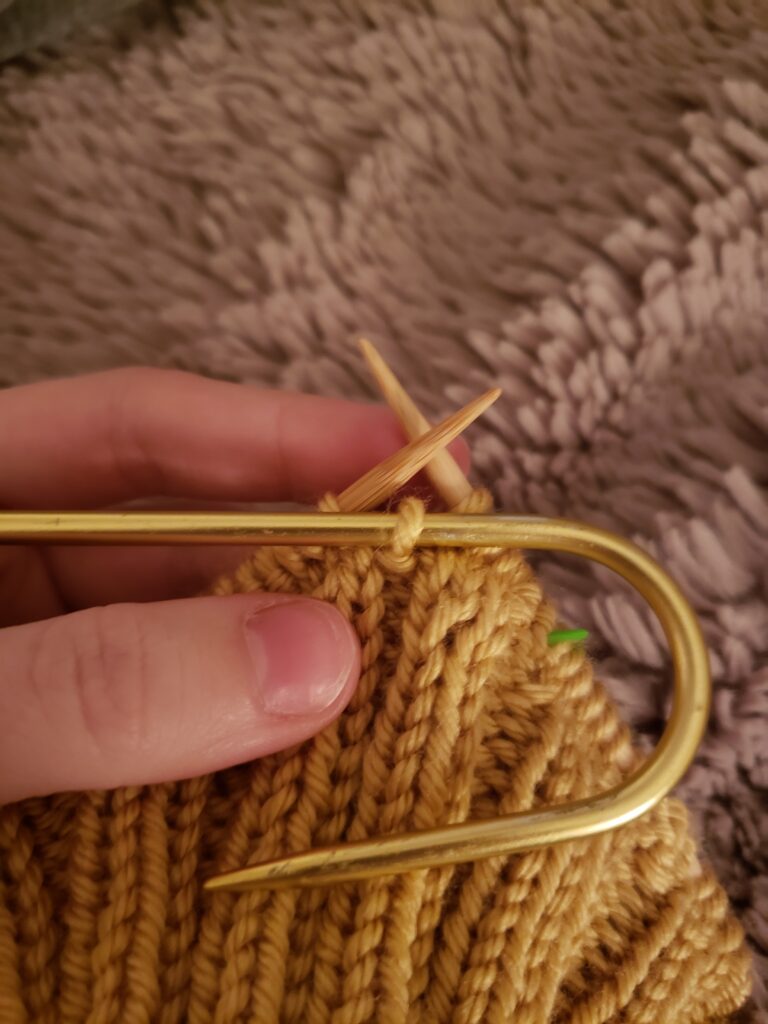

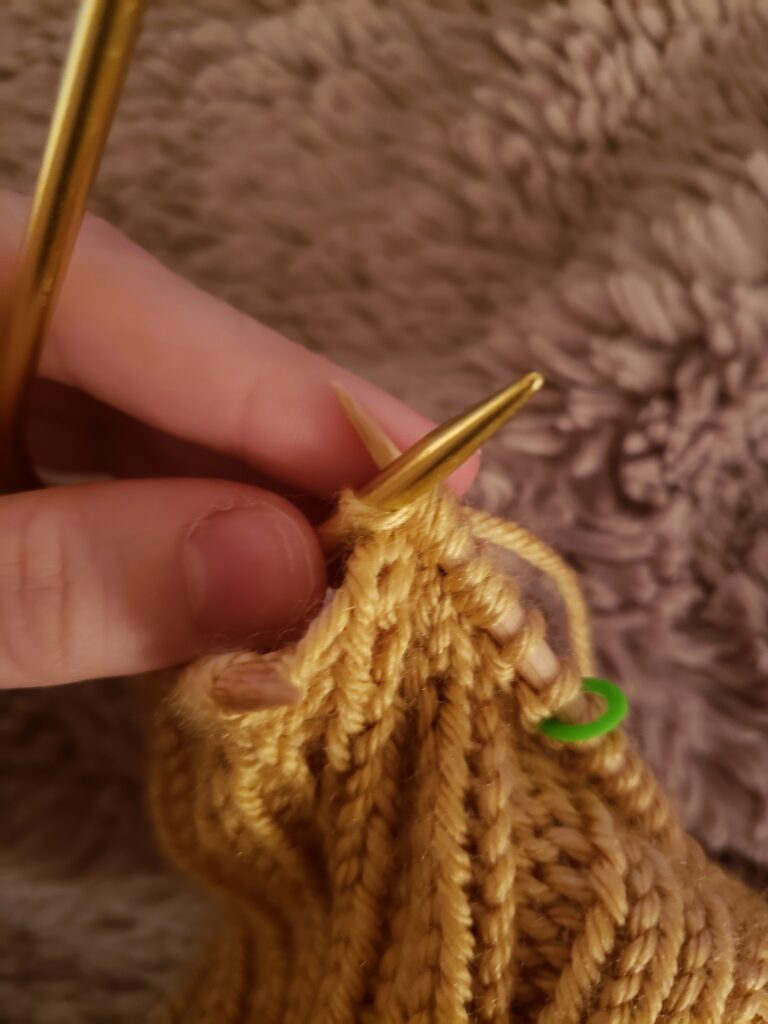

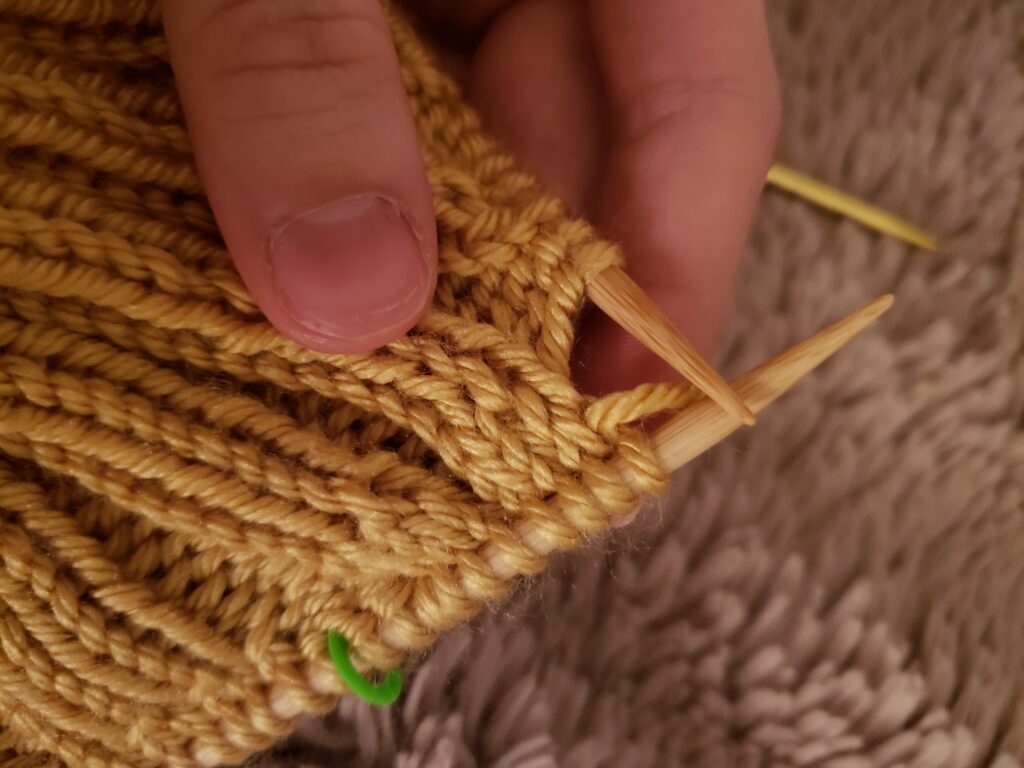

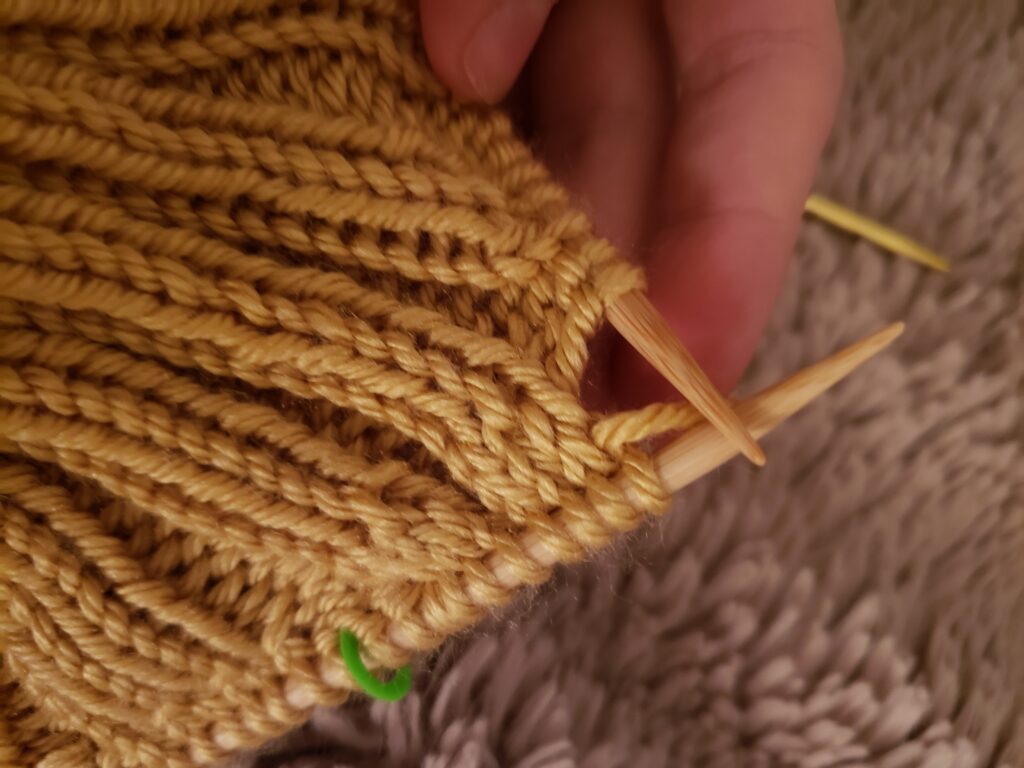

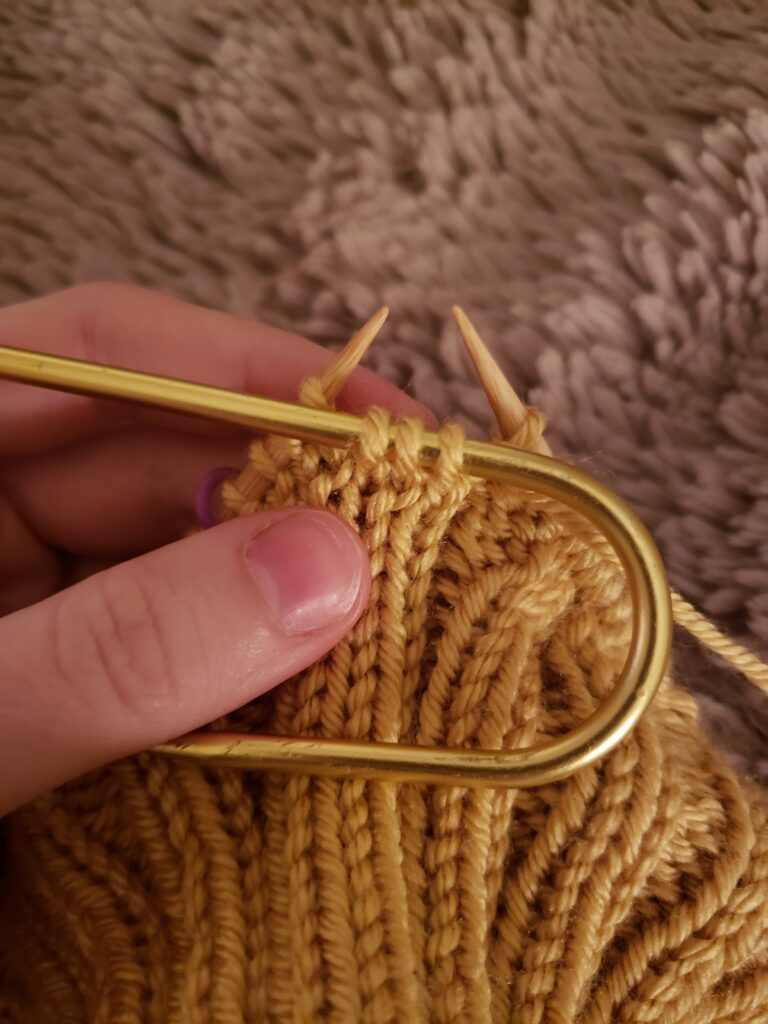

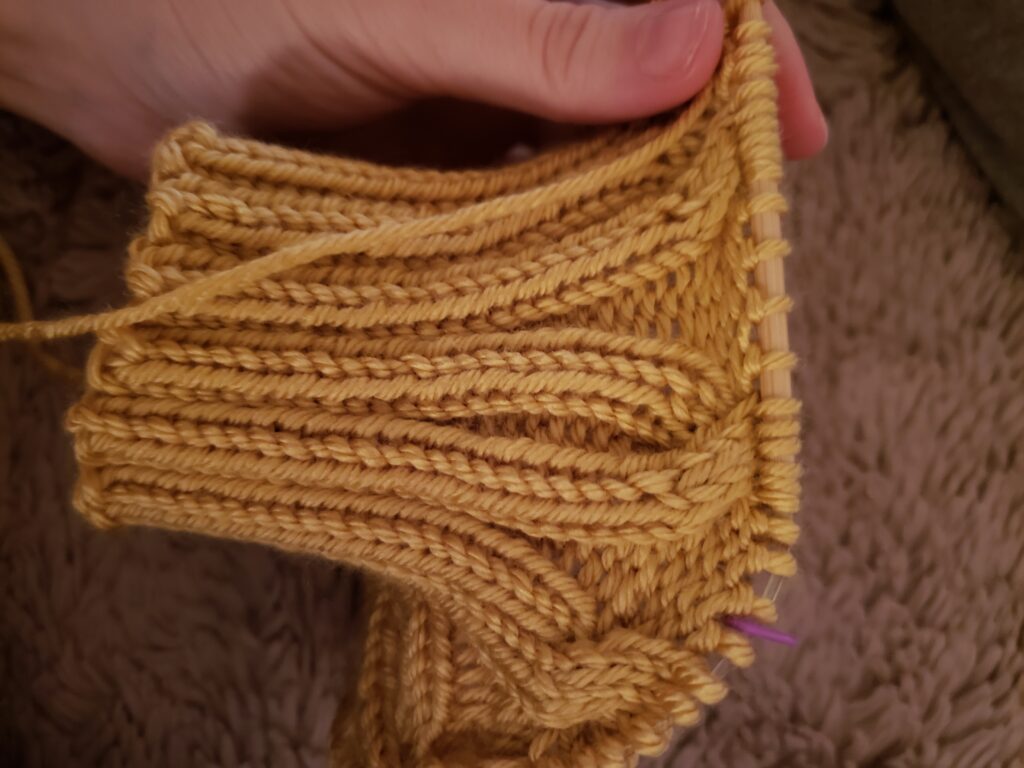

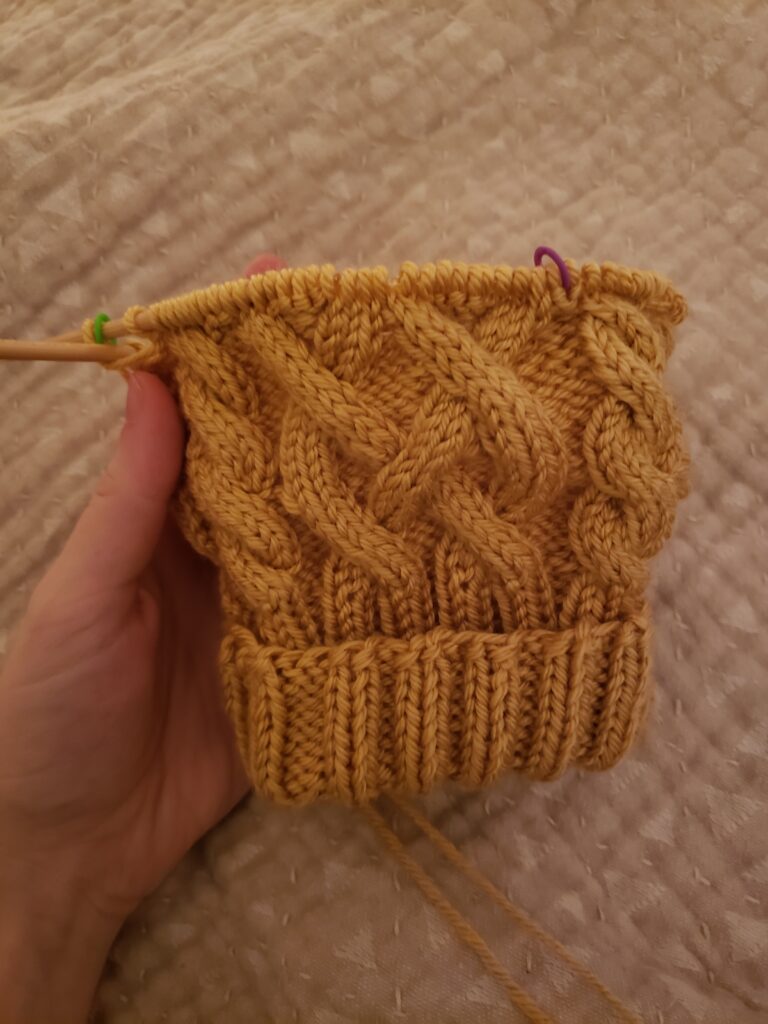

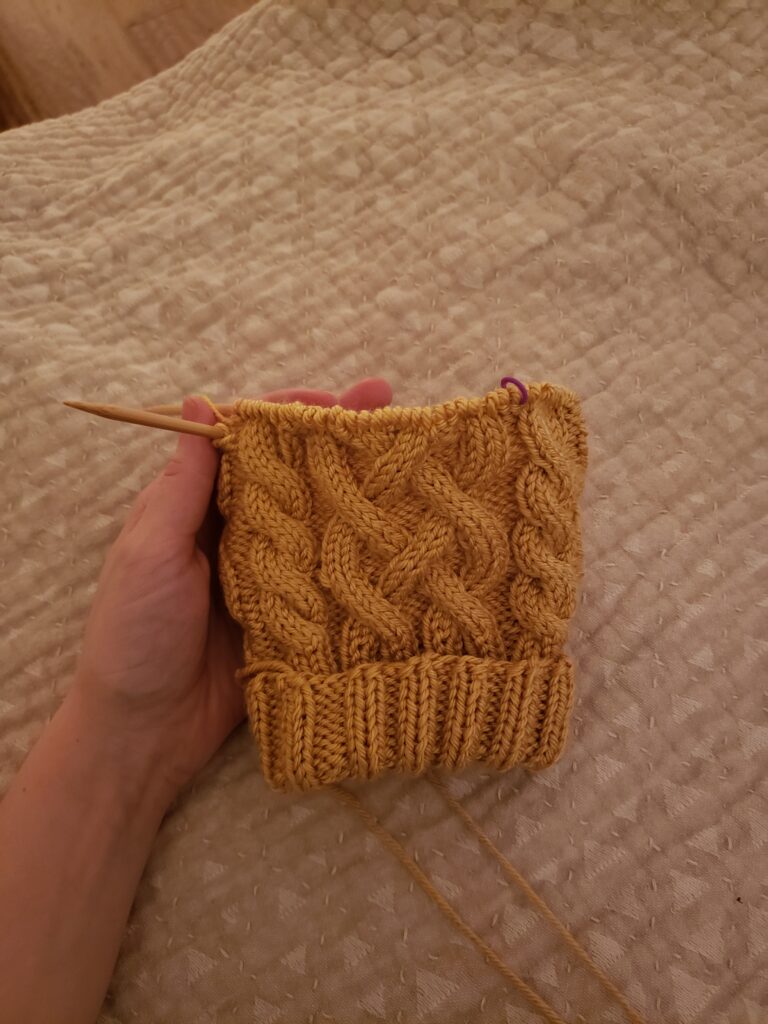

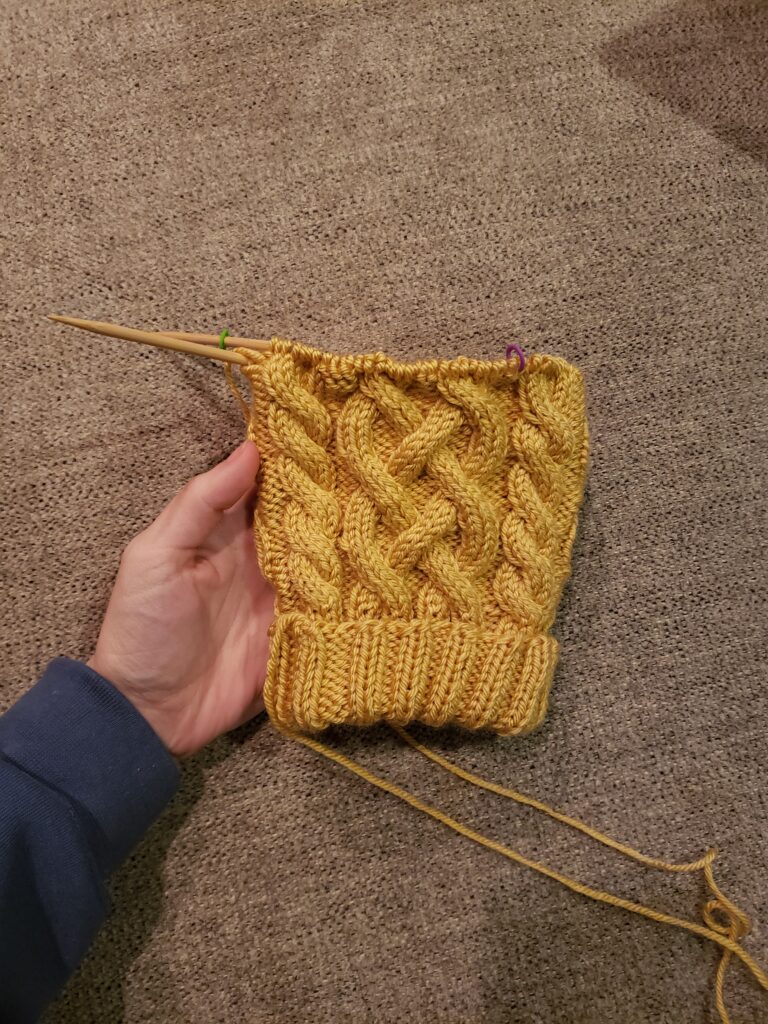

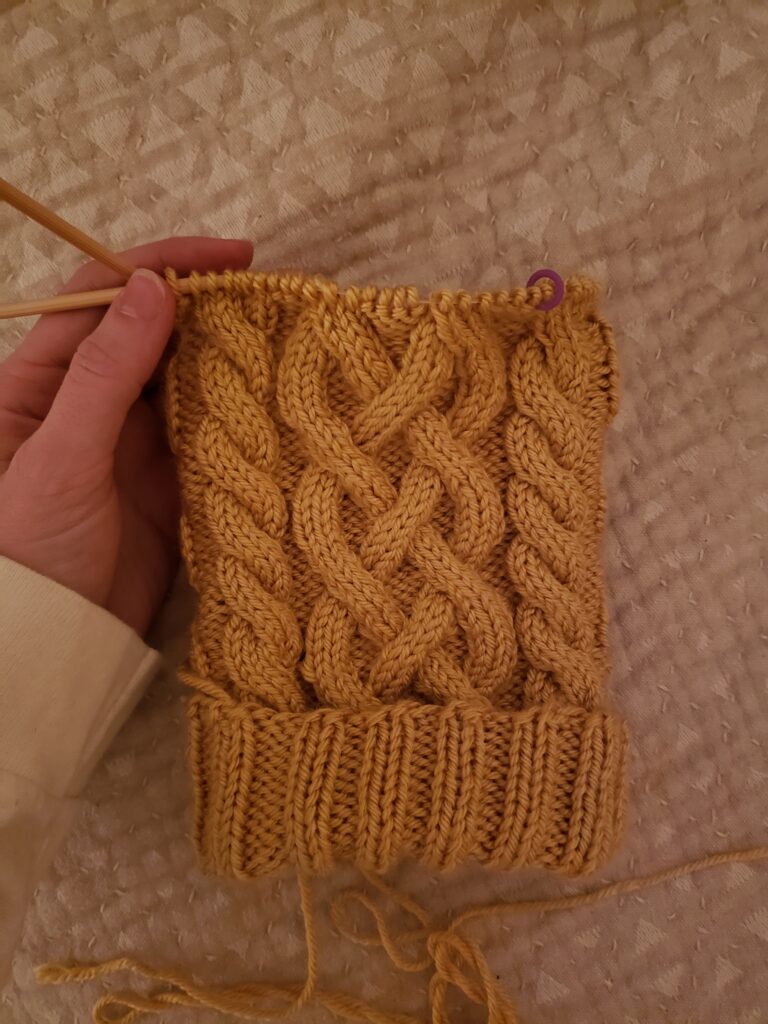

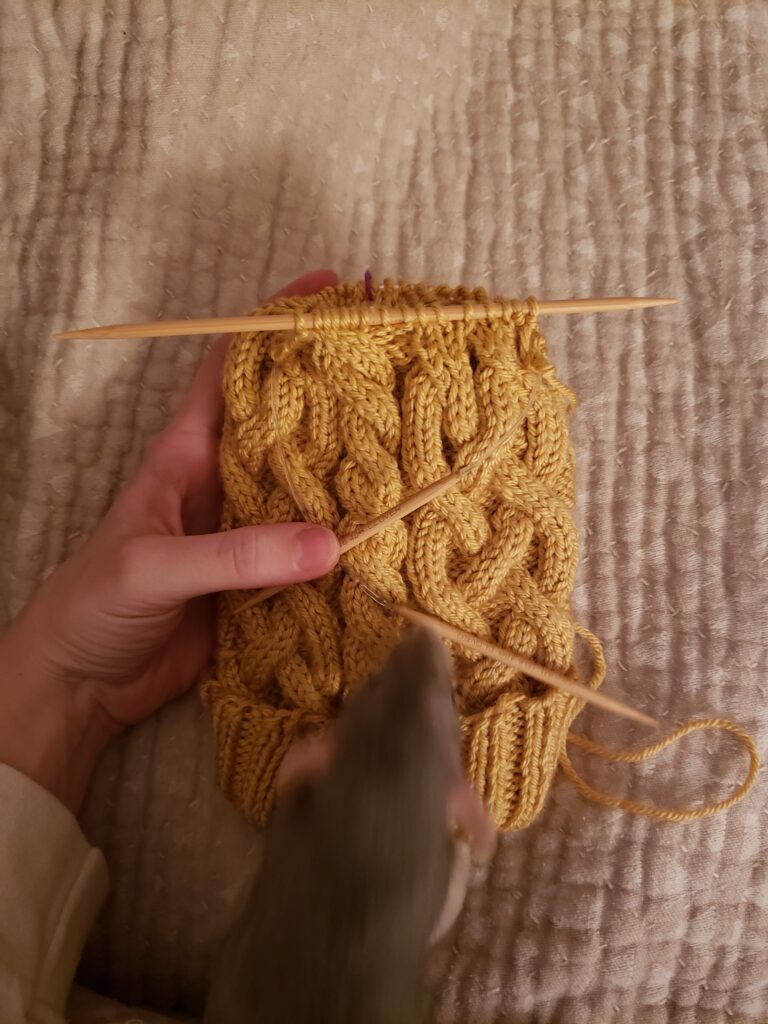

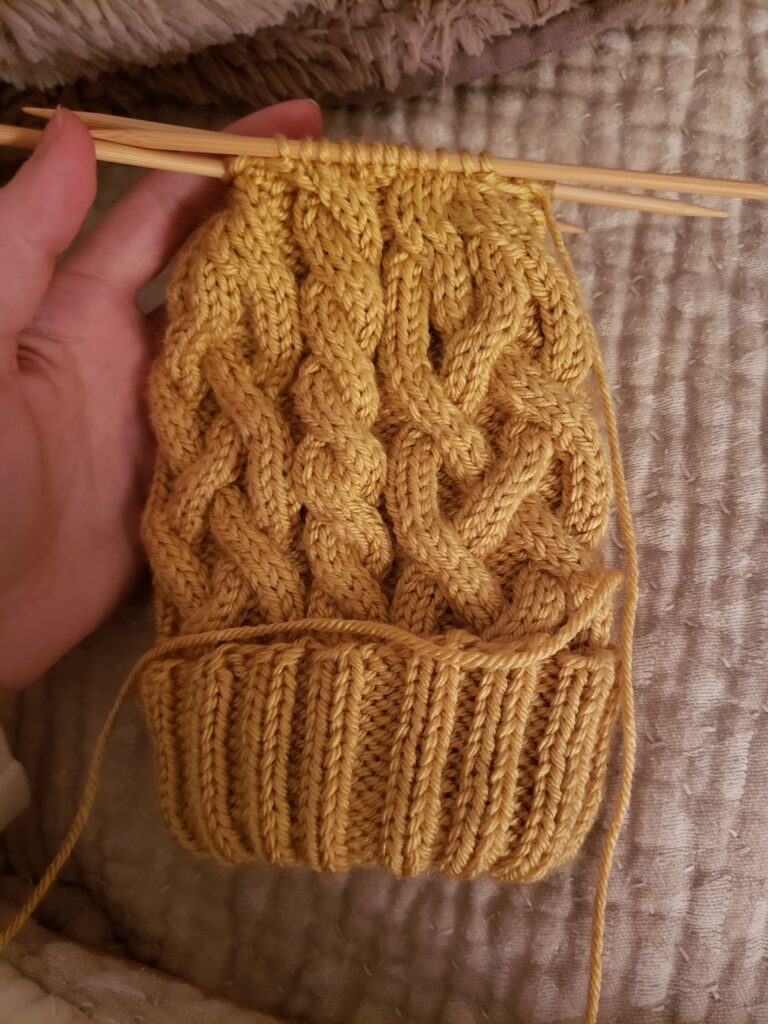

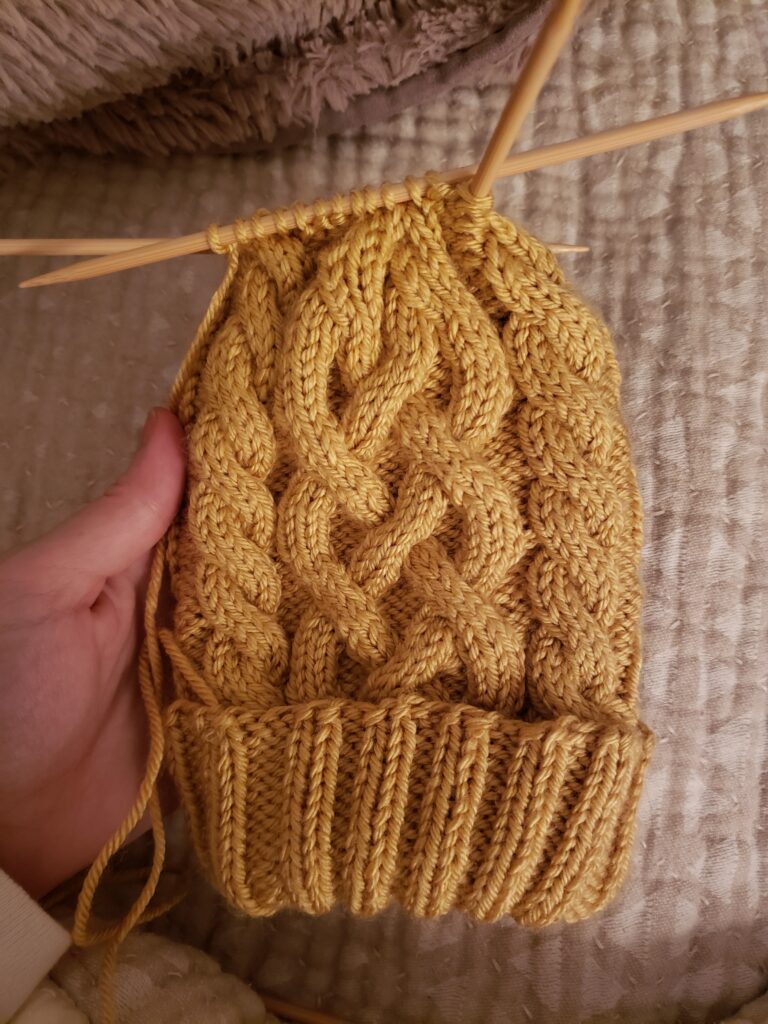

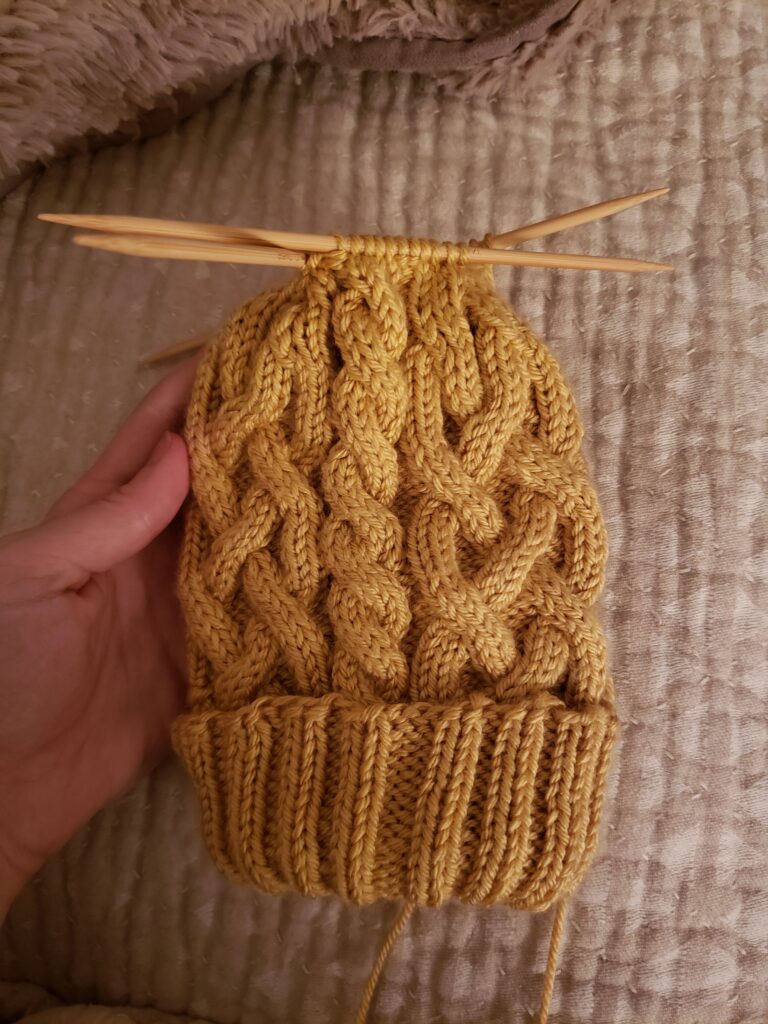

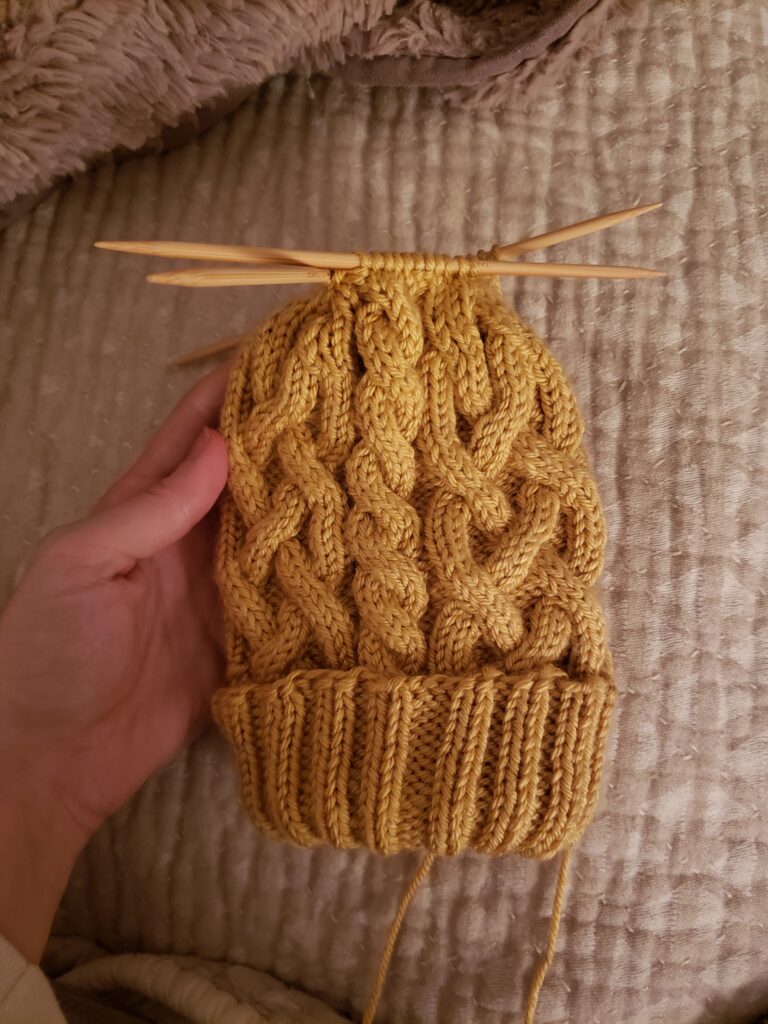

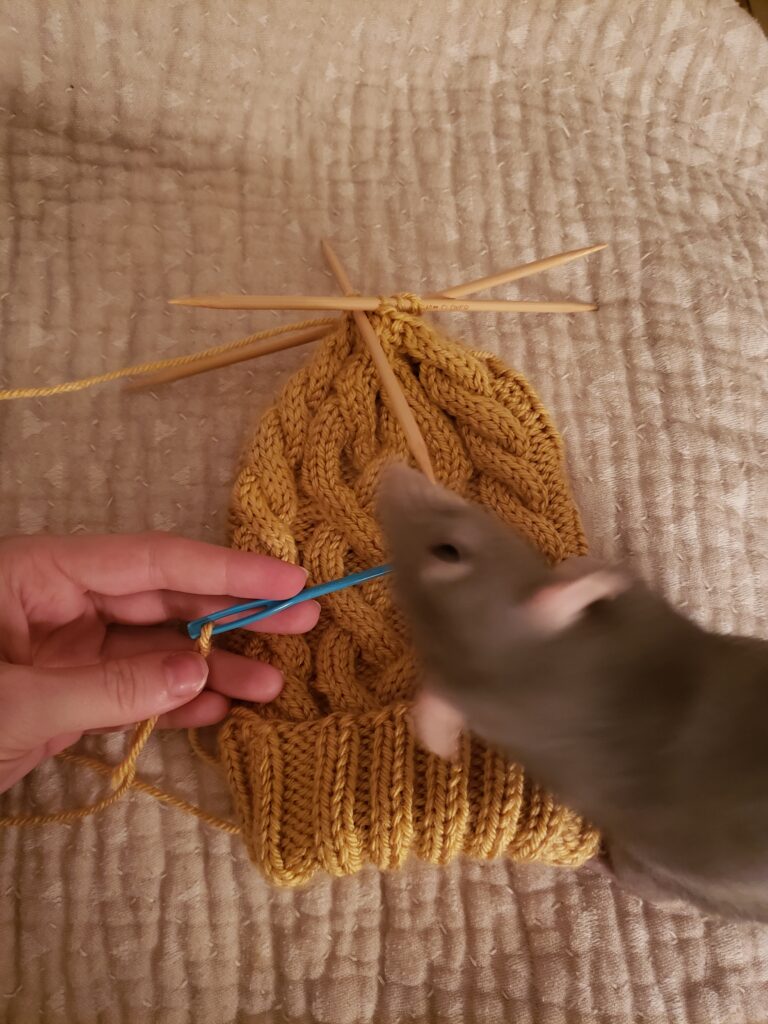

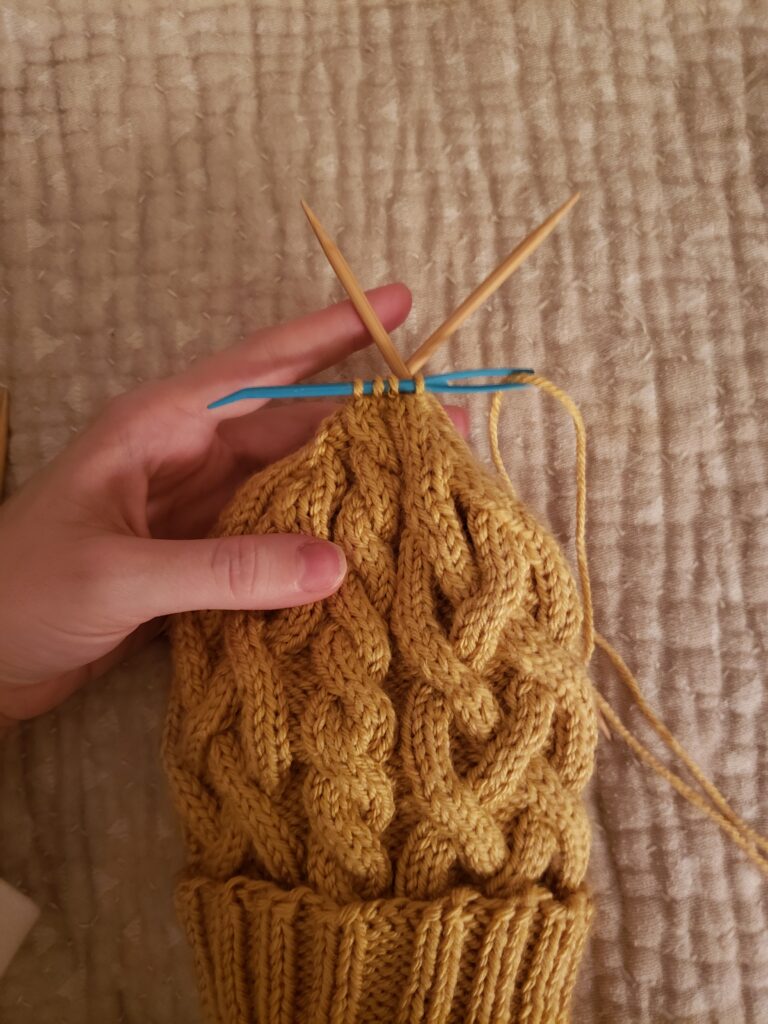

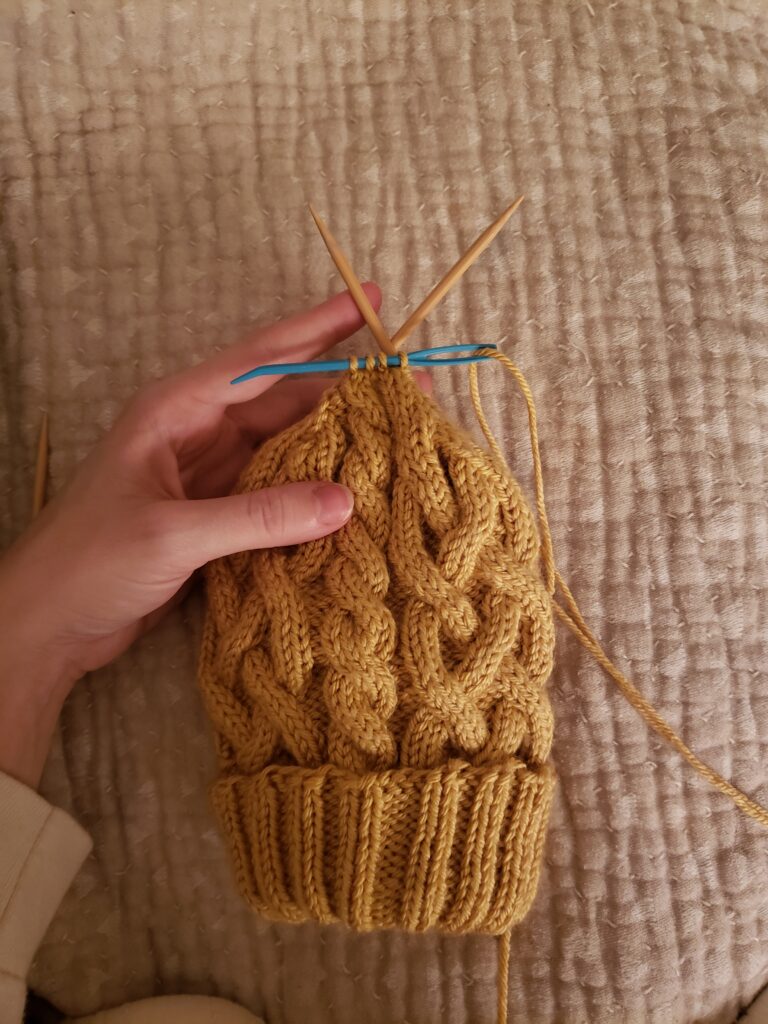

For our final project, I have decided to “play Rumpelstiltskin,” imitating as closely as I can Rumpelstiltskin’s act of turning straw into gold. Similar to the straw mentioned in the tale, yarn is commonplace, unimpressive, and inexpensive (mine cost $3). However, through the process of knitting the yarn into a garment (in my case, a hat), it transforms into something remarkable, beautiful, and much more valuable, like gold. Most of the time I spent knitting was between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m., which allowed me to experience the feeling of laboring through the night as Rumpelstiltskin does in the tale. I estimate that overall, this project took approximately 30 hours to complete, similar to the total time that Rumpelstiltskin would have spent spinning the straw over the course of three sleepless nights.

Pattern: “Traveling Cable Hat” from Purl Soho

Yarn: Caron Simply Soft Autumn Maize

Materials: Size 5 & 6 16” circular needles, size 6 double pointed needles, cable needle, stitch markers (3), darning needle, worsted weight yarn (approx. 80 yards)

Stitches used: Cast-on method of choice, knit, purl, k2tog, p2tog, ssk, c6f, c6b, left cross, right cross, bind-off method of choice

Photos of the process:

When people think of fairy tales today, they often think of the Disney versions that we grew up watching. Disney fairy tales are known for colorful animation, fun musical numbers, and above all a happy ending. And at first glance, the 2014 Cartoon Network miniseries Over the Garden Wall seems to follow these same tropes. It is animated, there are musical numbers, and I guess you could say it has a happy ending. But the animation is darker and more mysterious, the musical numbers are either folksy or sweeping and orchestral, and the final message of the show is really about death and dying, and the conscious choice to carry on living even in times of misfortune. I know what you’re thinking: This show doesn’t sound nearly as fun as a Disney movie. But after watching it many, many…many times, I have come to the conclusion that this show is a beautiful modernization of a Grimm fairy tale and can offer something to everyone, no matter their age.

Over the Garden Wall begins with two brothers, Wirt and Greg, wandering through a strange forest, which the narrator names “The Unknown.” They do not remember how they got to this forest or how to get home. In the first episode, they meet a girl-turned-bluebird named Beatrice who claims she can help them escape the forest, and the rest of the show follows their adventures trying to do just that while avoiding the mysterious antagonist known only as “The Beast.”

On the surface, Over the Garden Wall is similar to a lot of 19th century fairy tales. It involves two young children lost in the woods, reminiscent of “Hansel and Gretel” or “Little Red Riding Hood,” people cursed to take the form of animals, as in stories like “The Frog Prince”, and a mysterious woodsman, like in “Snow White.” The setting is hard to place but looks similar to the average person’s idea of Puritan America: farms, small towns, no technology. But the show manages to subvert traditional fairy tale tropes as well. While Wirt and Greg are clearly the Hero and Helper archetypes and the Beast is the obvious Villain, the other characters are much more complex.

One hilarious example of this is Sara, Wirt’s love interest. Throughout the show, Wirt refers to his unrequited love and laments the fact that he believes Sara likes another boy, Jason Funderberker, instead. He paints Jason as the stereotypical cool kid. But when we finally meet the two of them, Jason is nerdy and has a grating voice that immediately gets on your nerves, while Sara is clearly more interested in Wirt. Similarly, many characters blur the line between good and evil. We find out the Woodsman is helping the Beast, which is upsetting until we find out he is only doing so to save his daughter. We also learn that Beatrice, someone who has been our ally, is tricking the two boys, but only because she is trying to help her family escape a curse.

Many Grimm’s fairy tales are also rooted in religion, Christianity specifically, something Over the Garden Wall leans into. The Unknown itself is a type of Purgatory. The audience discovers this towards the end of the series when it is revealed that Greg and Wirt are actually from modern times. When hanging out with their friends on Halloween night, the two fall into a lake. As they sink to the bottom, they are transported to the Unknown. The purpose of the show is for Greg and Wirt to make a decision: do they continue to wander the Unknown and give into its temptations, or do they choose to return to the real world and continue living?

The Beast is a religious figure as well, more specifically a Satanic figure. He is the agent of death throughout the show. A terrifying monster who collects the souls of lost children. The Unknown acts as the Beast’s mechanism to trap people. Its forest is endless and the more you journey through it, the more hopeless you become until you finally give up. Most do not have the strength to outlast the Beast and he has clearly claimed many lives.

One life the Beast has allegedly claimed involves a character called the Woodsman. The boys meet the Woodsman in the very first episode. He tells them that his lot in life is to find the edelwood trees and grind up their branches to make oil to keep his lantern lit. Why? The Beast has trapped his daughter’s soul within the lantern, and tells him that keeping it lit is the only way to keep some semblance of her alive. Is this really living though? I’m not sure it’s a life many would choose. But the fear of loss is crippling for the Woodsman, and probably the

audience themselves, and the Beast plays on this fear even further by asking the Woodsman to lead him to the two boys. If he can do this, the Beast claims he will see his daughter again. A life for a life.

Greg is our symbol of optimism throughout the show while his brother slowly starts to lose the will to carry on. Seeing that Wirt is about to be claimed, Greg makes a deal with the Beast. The Beast has Greg do various complex tasks, clearly designed to wear him down. At one point, the Beast tells him, “I thought you’d give up,” and Greg responds, “Give up? I’ll never give up.” Greg’s unwavering optimism allows him to refuse to give in to the Beast and, by extension, death. He is too excited about life to want it to end any time soon, no matter how hopeless things seem. He is making a conscious choice to continue to live.

Eventually however, the Beast is able to trick him into staying still long enough for a tree to begin to grow around him, trapping him in the forest. When Wirt finds him, he is weak and seemingly close to death. While Wirt tries to save him, the Beast calls the Woodsman. Greg has turned into an edelwood tree at the perfect time: the Woodsman is running out of oil. The realization on the Woodsman’s part that he has been burning children’s souls is a heartbreaking one and shows the cruelty and manipulation of the Beast. When the Woodsman protests

that he did not know, the Beast replies, “And would it have mattered?” This touches on a chilling theme: the love that a parent has for a child or that Greg and Wirt have for each other, seems to overshadow any bad deeds. They are willing to do anything for each other, even if that means causing the deaths of others, at least that is the Beast’s idea.

The Beast finally tries to conclude his plan: he wants Wirt to take on the task of lantern-bearer, keeping Greg’s soul alive inside the lantern. On the brink of giving in, Wirt suddenly has an epiphany, and a funny one at that. His heroic and defiant words are, “Wait, that’s dumb.” If he agrees to be the lantern-bearer, he would be trapped in the Unknown as well. That is not what Greg would have wanted. Even in the face of serious loss, Wirt has to choose to continue living. He gives the lantern back to the Woodsman, and after choosing to live, escape is suddenly easy. He and Greg leave the Beast behind. Suddenly, the two wake up in the hospital, having been rescued from their near-death experience.

Classic fairy tales always have some sort of moral. This is why they were so popular. Children and adults alike could read them and get something relevant out of them. And the moral of Over the Garden Wall is clear. This show equates giving up to dying, and that death is a scary one, filled with monsters. So no matter what happens, you have to push through. Never give up, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. In short, be more like Greg. This is something Wirt learns to do throughout the show and it pays off. The two return home stronger, braver, and more prepared for the world ahead of them than ever.

Many finish this show and are stuck on one particular question. Was the Unknown ever actually real? And to that, I’ll leave you with the words of the Beast: Would it have mattered? Watch the show, explore the magic of this strange and beautiful world, see what you take away from it. And then hopefully, you’ll have your answer.