By: Taha Douhaj

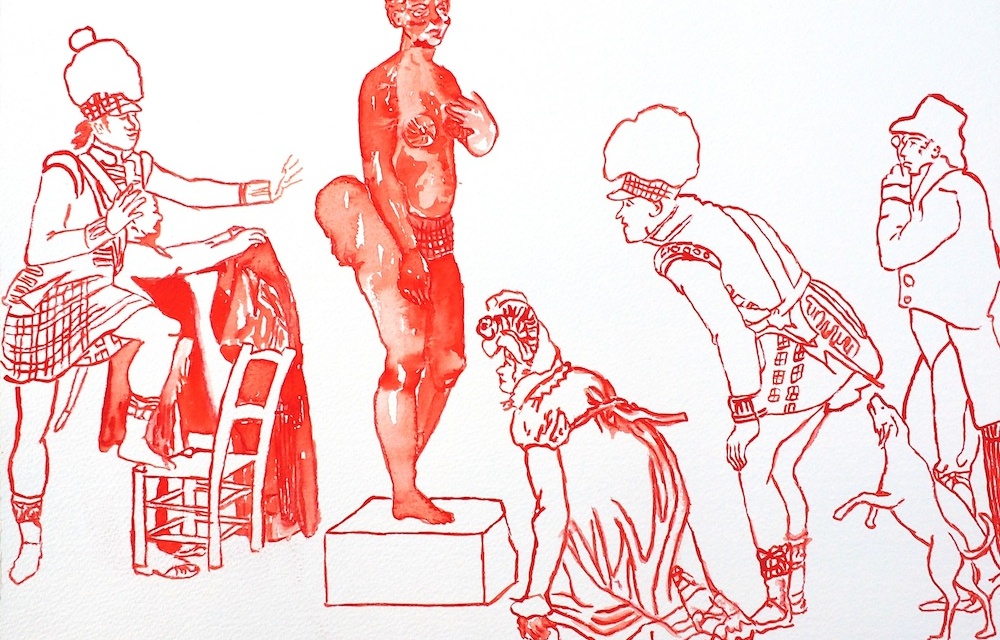

Rows of people talking and whispering amongst themselves, all one step closer, and one shilling poorer. They whisper and discuss in eager excitement about who or what they are about to see. It’s 1810 and in London, the Piccadilly circus is exhibiting what they call on pamphlets as the “Hottentot Venus.” A group of kids and adults alike squeeze and fight their way through a huddle of incoherent whispers. Rumors spread that if you spend one more shilling you can poke the exhibition. The lights start to dim and the curtain begins to flap signaling the unveiling of what the circus calls “The missing link between man and beast” (Imma 137).

Sarah Baartman was a Khoisan woman taken from her home in the cape of South Africa to become a circus animal due to having steatopygia, which caused a build-up of fat in her buttocks. Sarah would get on stage, and be put in a cage by an actor acting as her “trainer.” This trainer would then tell her to sit and stand as he did to the other circus animals (Gordon-Chipembere 10). This correlation of hypersexuality and beastification towards black men and women was sparked by Bartman and countless other exploited black bodies. This vaudevillian way of thinking is reflective of a racist synchronicity between animals and Africans, an idea that still persists in our modern-day society. Forever immortalized in the pages of stories and strips of celluloid in films, “the missing link between man of beast” occurs in subliminal means. Instead of paying a shilling to watch or poke Sarah Baartmann, we now pay $10.00 a month, and that’s if you want ads.

There was something peculiar that struck me about Baartman shows, in every ad Baartman shows were indiscriminate of age and welcomed children (Kelsey-Sugg 1). It was as if this hyper-sexuality and animal-fication of black bodies were something that must be embedded in minds of all ages, young or old. A social dogma is then created in which a correlation between black body and beast was seen as obstinate and true. Today not only is this hypersexualization and animalification seen in adult mediums, akin to porn or adult-themed films or texts; it is as well subtly ingrained in children’s fairy tales and Disney movies. This essay will uncover and delve into a phenomenon, in Disney Pixar animated fairy tale films, that have their black characters transform into animals for a majority of their screen time. Even with intentions of right full representations and a black crew and cast this phenomenon still exists in movies like The Princess and the Frog and new releases like Soul. In relation to the movie The Princess and the Frog anthropomorphic representation is used with racist iconography and caricatures that are explained by antiquated racist beliefs and origins that have still persisted in our modern-day media, but now occur through subliminal means. Therefore, if a light is shined on this unconscious phenomenon and its malicious origins, there can be a hopeful chain reaction from awareness to action.

Origins

“Some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as at present between the negro or Australian and the gorilla” (Darwin 236). In Charles Darwin’s 1871 book The Descent of Man Darwin’s theory claims Africans and aboriginal Australians are more closely related to apes than the Caucasians of the European continent. Darwin’s ideas and theories permeate through classrooms and lecture halls across the globe. The glorification of Darwin’s works signifies a universality of his ideas that is not only applicable to the world of academia, but as well as the cultural economy of a society, however as a society, no matter Darwin’s positive and progressive ways of thought, one must not ignore the perversions of ancient thought. In the world of academia African bodies have been related to animals as evidence of racist ideologies equating black bodies to being either subhuman or, as Darwin describes, “savages..with hideously perforated lips, nostrils, or ears, and distorted heads” (495). When multiple respected scholars and scientists use the idea of the Animification of black men and women in scientific journals, these correlations then seep into our entertainment and cultural spheres of influence.

Circuses and plays of the past would use black inferiority as a plot device and or as evidence. Sarah Baartman, as aforementioned, was a byproduct of scientific studies and experiments using the African continent as one big experiment to test the ideas of Black civilization and inferior to the civilizations of the West. When Baartman died in the house of S. Reaux, her animal trainer used in shows, the first on the scene to carry her exhausted 26-year-old body was first “a team of zoologists, anatomists, and naturalists”(Chipembere 10). European construction of African and Animal continued for years seeping into art and literature, “Europeans were seen to be in the most superior position and Africans in close developmental proximity to animals” (Imma 138). Art later embraced pervasive stereotypes of African Americans such as the Mammy, Uncle Tom, Black Buck/Brute, etc. To describe black men and women as either lazy, violent, and above all Animalistic. These stereotypes were formed, and some were even inspired by “discoveries” and exploitation of Sarah Baartman and others.

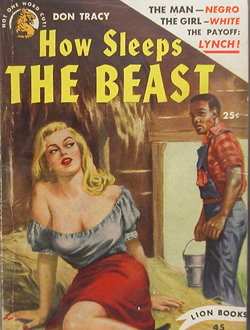

“How Sleeps the Beast” Tracy 1954

“The Black Buck” in the film “The Birth of a Nation” 1915

In films and racist cartoons and novels, black men and women are represented to have beast-like and animalistic tendencies. Like the “buck,” as represented in the film “The Birth of a Nation”, the buck is a symbol of the racist correlation between animals and Africans that was prevalent in American cinema (Bogle 37). One company that was a part of a cinematic boom in the early 20th century was Disney. Although Disney fairy tale films depict worlds of talking animals, these animals are still not separate from, “Darwinian concepts of “survival of the fittest,” in which only the fiercest animals survive” (Condis, 2015). However, a trend in old and new Disney movies is a piece of imagery that is symbolic “Disney films depict Black characters as having a deeper connection to the beast within them, thereby perpetuating racism” (Dundes and Streiff 2016). Every piece of art is filtered and processed through a primary perspective or gaze. Disney’s lessons on dominant presuppositions are reflections of Western society and ideals. By utilizing fairy tales as the base of their films a reflection of a company that embodies family and wholesome values. It is these inherent biases from outside society and dominating presence in cultural spheres that make Disney films not only influential but dangerous.

Disney’s representation of black characters through the years is seen as problematic and reflective of a past dominant Gaze of a racist zeitgeist. In old Disney films like Dumbo (1941) a group of animated crows are used to help Dumbo learn how to fly. These characters are dressed in stereotypical African American garb and speak in African-American Vernacular English (AAEVE), being portrayed as a group of caricatured black men. The leader of these black crows is named “Jim Crow.” This history of obviously racist characters was met with criticism in later years. In response to racial criticism Disney started to develop a film with the goal to have a female black lead (Enoch 6). However, racial stereotypes still persist and an anthropomorphic transformation that changes a black character for more than half their run time occurs in the film. Disney moved from obvious racist characters and moved to subtly depict them.

The Princess and the Frog

Although Disney tried to make The Princess and the Frog to dismantle previous notions of a racist past, this mission is absolved when the film is viewed through a critical eye. Tiana and other black characters are presented as animals. Not as beautiful swans (The Swan Princess 1994) but as swamp-dwelling creatures like frogs, crocodiles, and horse flies lathered in mucus. Louis, the crocodile, recalls a memory in which he tries to join a band and is met with utter disgust and fear, there is an inherent disgust interpreted with these creatures.

When Tiana first discovers the prince as a frog she instinctively beats the frog with a book in utter revulsion. These animals are not met with love, like Snow White and other woodland creatures, but black characters–as these creatures–are treated as subhuman and must be either exterminated or met with fear. Tiffany Tyantan Enoch, a media scholar at the University of South Carolina notes that “Tiana spends more time as a frog throughout the course of the movie (57 minutes of the film’s 97-minute running time) than she does as a human being—let alone as a princess” (Enoch 10). Disney’s first black Princess is an animal for more than half of her run time. This assumption of black people and animals are a reflection of broader historical and cultural contexts. This subhuman representation of black men and women compared to white elites is a motif that reinforces ideas of black inferiority in the eyes of a white-dominant gaze that elicits control and power. Her runtime makes her Disney’s first animal princess and this fear of putting a black woman on screen is scary to the company, by putting a “stand in” for her there is an attempt to save face. It’s important to note that Tiana is molded to be the amalgamation of two black Jim Crow media stereotypes: The Jezebel and The Mammy.Although Disney tried to make The Princess and the Frog to dismantle previous notions of a racist past, this mission is absolved when the film is viewed through a critical eye. Tiana and other black characters are presented as animals. Not as beautiful swans (The Swan Princess 1994) but as swamp-dwelling creatures like frogs, crocodiles, and horse flies lathered in mucus. Louis, the crocodile, recalls a memory in which he tries to join a band and is met with utter disgust and fear, there is an inherent disgust interpreted with these creatures. When Tiana first discovers the prince as a frog she instinctively beats the frog with a book in utter disgust. These animals are not met with love, like Snow White and other woodland creatures, but black characters–as these creatures–are treated as subhuman and must be either exterminated or met with fear. Tiffany Tyantan Enoch, a media scholar at the University of South Carolina notes that “Tiana spends more time as a frog throughout the course of the movie (57 minutes of the film’s 97-minute running time) than she does as a human being—let alone as a princess” (Enoch 10). Disney’s first black Princess is an animal for more than half of her run time. This assumption of black people and animals are a reflection of broader historical and cultural contexts. This subhuman representation of black men and women compared to white elites is a motif that reinforces ideas of black inferiority in the eyes of a white-dominant gaze that elicits control and power. Her runtime makes her Disney’s first animal princess and this fear of putting a black woman on screen is scary to the company, by putting a “stand in” for her there is an attempt to save face. It’s important to note that Tiana is molded to be the amalgamation of two black Jim Crow media stereotypes: The Jezebel and The Mammy.

The Jezebel stereotype is a Jim Crow-era stereotype that portrays the victim in the otherness faced by black Americans. Sarah Baartman was the original Jezebel, a victim of adverse sexualization and animalization, “the Jezebel is representing wild animals by using Black characters—particularly, Black women—creates an “otherness” that divides them from civilized society and is represented by the “Jezebel” archetype” (Enoch 14). Promiscuous and lacking self-control of one’s sexual proclivity and others is the Jezebel. As if he is programmed by a gaze of sexuality, Prince Naveen responds to Tiana as if she were a “Jezebel.” After fleeing from a group of alligators, Prince Naveen and Tiana are stuck in a hollow tree and forced to interact. This confined space has Naveen tell Tiana, “Well, waitress, looks like we will be here for a while. So, we might as well get comfortable” (The Princess and the Frog, 35:35-35:45). Tiana constantly refuses Naveen’s sexual advances and is played off as a joke throughout the film as if her “No’s” would transform into “Yes’s” in the blink of an eye.

Blood sweat and tears are what make up the Mammy stereotype. A pre-Civil War/slavery stereotype of the Black maid or help, that finds solace in aiding whites then her own liberation. From Vaudeville stages to being the first film shown in the White House: The Birth of Nation. The hardworking servant of a white family is a trope still seen today. Tiana is one of the only princesses whose hard work and labor are done through voluntary servitude and ambition. One scene that strikes this trope to its core, is in the first act of the film in which Tiana prepares for her work and waits tables at dinner, this dinner rush means that Tiana must take the load of three waitresses. In true Mammy fashion, although sleep-deprived and angry, Tiana saves face and hides her true feelings and pretends to be happy, “Tiana’s multiple jobs are not presented as a consequence of oppression and racial disparity, but rather as a sign of character development and a way to achieve the American dream” (Gregory, S.M., 2010). These stereotypes and lack of physical/virtual representation of a black face to the face of a green frog are detrimental. When little girls watch a film and eagerly look for a movie that is representative of them, a problem arises when an animal then acts as a substitute for that representation.

Disney’s dominant and powerful gaze has the ability to portray a beauty standard reflective of a zeitgeist and for a black woman to be that princess and figurehead for said beauty standard is just rectifying a past wrong. There is a subconscious association between black characters and animals, seen in films like Soul 2020, Brother Bear 2003, and Emperors New Groove 2000 have black or minority characters turned into animals. “The continued depiction of Black characters as animals (e.g., frogs) … reinforces harmful stereotypes and prejudices, thereby promoting the idea that Black people are subhuman and undeserving of the same rights and dignity as white people” (Enoch 8). If these racist correlations between African and Animal exist even now but occur through subtle and subliminal means; the problem is not gone but now is hidden.

The Gaze

Is this bestialization of carnal representation of black bodies a voluntary practice or is it a mere remnant of a racist past? Now this animalistic representation is a tenant of something more symbolic, something more appalling. When creators like Oprah Winfrey act as, not only voice actors but consultants of the The Princess and the Frog and these correlations still exist then what can be the solution? Again when black writers and producers exist in movies like Soul and this correlation still persists there is a problem that is being understated.

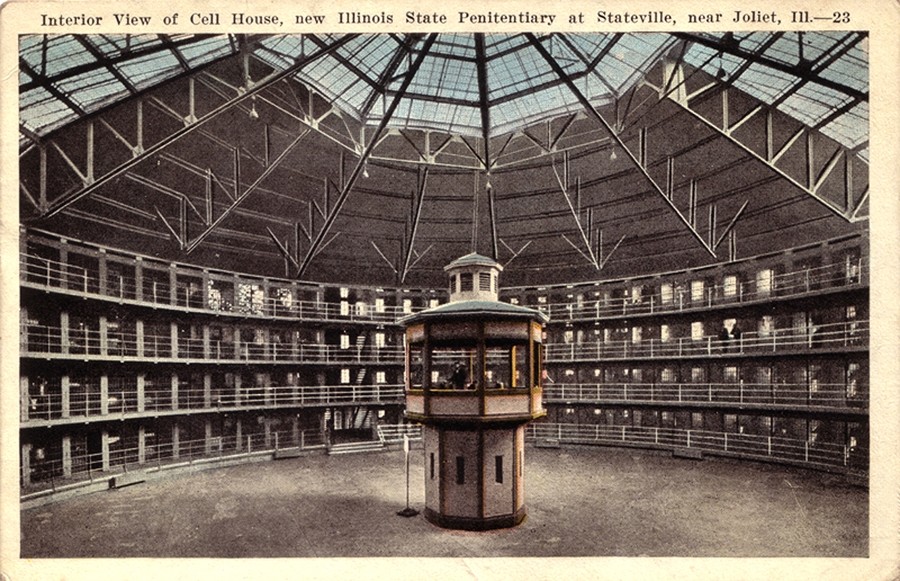

Drawing on Micheal Foucault’s Panopticon analogy, an examination of how external and internal forces contribute to the oppression of the black minority. Micheal Foucault, a 20th- century French philosopher, examines the “gaze” of society and how surveillance and observation function as mechanisms of power within disciplinary institutions. Foucault elucidates this power in his analogy of prisons. Describing a design of a prison called the panopticon. Foucault elucidates how the panopticon’s design, featuring a central watchtower enabling continuous monitoring of inmates, embodies a power mechanism reliant on perpetual surveillance. This surveillance instills a sense of visibility and control, prompting inmates to internalize the sensation of being observed and adjust their conduct to align with expected standards. Foucault contends that the panoptic structure, characterized by the omnipresent gaze of the observer, extends beyond the physical confines of the prison to infiltrate various societal domains. He further suggests that even if the watchtower were to become tinted and inside is no observer, the power of the gaze still persists and permeates every cell block. This internalized power shapes individuals’ behavior, disciplining them to adhere to societal norms even without direct oversight. Even when no one is in the tower, inmates still feel the power of the gaze and structure their lives around the gaze of someone not even there.

To utilize this idea within media literacy black oppressive stereotypes and anamorphic representation exist within the black creators, because of an innate/inmate programming. This internalization of the dominant gaze can lead to self-objectification and internalized oppression, wherein individuals come to see themselves through the lens of the dominant culture and internalize negative stereotypes about their own identities. This animal-fication of black characters is a byproduct of generations of programming from a dominant disciplinary gaze, and creators still act within the realms of this gaze. When no one is watching these creators act within the confines of the gaze shackled to a domination that lies dormant beneath the pages of frames of a piece of art. The impact of the dominant gaze extends far beyond explicit acts of censorship or control, infiltrating the very essence of artistic expression and perpetuating cycles of oppression. It underscores the need for critical engagement with the power dynamics inherent in storytelling and the importance of dismantling oppressive structures to foster authentic and empowering narratives. By acknowledging the pervasive influence of the dominant gaze and working to dismantle its hold, we can strive towards more inclusive and equitable representations in media.

Conclusion

When starting this analysis there was a meager amount of information on the topic. If a light can be shown on this phenomenon and a spotlight on a racist past one can expand their lens of media literacy and view art through another more critical lens. Because of the lack of information on the phenomena, there exists a problem of unawareness that can drive this problem forward and this subconscious correlation between a minority and animals will linger in cultural spheres. If these antiquated disciplinary gazes continue to define us, we will not be free but will continue to be prisoners disciplined by an invisible eye. By first being aware of the origin and history of malicious black representation, and understanding a phenomenon that is a remnant of said history, one can be informed. If enough regular viewers can be aware of these racist souvenirs of the past a critical eye can be formed that can be used for all media; nevertheless, awareness does not stop at the viewer, but to future artists who can be aware of the very gaze they work under. A chain starting from awareness to action can be directed. Let the sins of the past die and let us be aware and truly evolve into a society no longer shackled by the ghosts of the past, but guided by new beacons and horizons. No longer guided by spotlights from watchtowers but now by the lights of our own flashlights. If society cares to move forward, a reflection from the past is necessary: Baartman’s people, the Khosian say “When the moon dies every month, let the sin in me die with it. When the moon is reborn each month, let the good in me be reborn with it.”

Works Cited:

Bogle, Donald. “Toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, and bucks: An interpretive history of

Blacks in American films.” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001.

Condis, Megan. (2015). “She Was a Beautiful Girl, and All of the Animals Loved Her: Race, the

Disney Princesses, and their Animal Friends.” Gender Forum, No. 55, pp. 1-12.

Darwin, Charles. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. Vol. 2. D. Appleton, 1872.

Dundes, L., and Streiff, M. (2016). “Reel Royal Diversity? The Glass Ceiling in Disney’s Mulan

and [The] Princess and the Frog.” Societies, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 35. Retrieved from: doaj.org/article/cbcbd23633b442c3bf32f5fca278ba07

Enoch, Tiffany Tyantyan. Animal Representation of Race in The Princess and the Frog.

Diss. University of South Carolina, 2023.

Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism.” The Information Society Reader. Routledge, 2020. 302-312.

Gordon-Chipembere, Natasha, ed. Representation and black womanhood: the legacy of Sarah

Baartman. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Gregory, Sarita McCoy. (2010). “Disney’s Second Line: New Orleans, Racial Masquerade,

and the Reproduction of Whiteness in The Princess and the Frog.” Journal of African American Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 432-449.

Imma, Z. (2011). “Just Ask the Scientists”: Troubling the “Hottentot” and Scientific Racism

in Bessie Head’s Maru and Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy. In: Gordon-Chipembere, N. (eds) Representation and Black Womanhood. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Kelsey-Sugg, Anna, and Marc Fennell. “Sarah Baartman Was Taken from Her Home in South

Africa and Sold as a ‘Freak Show’. This Is How She Returned.” ABC News, ABC News, 17 Nov. 2021, www.abc.net.au/news/2021-11-17/stuff-the-british-stole-sarah-baartman-south-africa-london/100568276.

Musker, John, and Ron Clements. The Princess and the Frog. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2009.