By Luke Ridder

Fairytales are known to be universal. Their appeal extends beyond age or nationality and the tales themselves reflect emotions, dilemmas, and characters that anybody can relate to. The same is often said for art, the universal language. Therefore, it is no wonder that art and fairy tales have become so inseparably intertwined. A union of two ubiquitous forms of human expression, creating one beloved experience. In other words, a symbiotic relationship in which each partner elevates and benefits the other. In order to demonstrate this relationship, we will explore the transformative effects of illustration, highlight art and artists that have benefited from fairy tale inspiration, and detail how fairy tales transformed the animation industry.

The oldest and most common fusion of art and fairy tales is found in illustrated stories. A staple of nearly every childhood and for good reason, as the benefits of illustrations and fairy tales themselves in developing literacy, creativity, and emotional expression among children are widely documented. As said by Einstein, “If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be very intelligent, read them more fairy tales”.Words on a page to a child do not have sound or meaning, it is only through memorizing the definition given by another where they can extract anything from them. This can be an arduous process for everyone involved, and it requires the child to draw knowledge from an outside source. However, illustrations are able to expedite this process dramatically, for while the letters of the word “ice cream” mean nothing to a child they will undoubtedly recognize a drawing of a bowl of ice cream. Allowing a child to draw on their own knowledge in this way will significantly strengthen and expedite their literary abilities. As is described in the article How illustrations affect parent-child story reading and children’s story recall, “Exposure to information both verbally and pictorially may result in the construction of memory representations in both modalities that then provide redundant retrieval routes” (Greenhoot et al.) This benefit applies especially to fairy tales, as their fanciful topics may initially leave a child lost. An illustrated tale however will not only aid their understanding of major plot points, characters and setting, but greatly increase their retention and enjoyment of the tale itself. Having the visual aspect to the tale stimulates the mind further, making the experience more engaging for a younger audience. This will ultimately foster a greater love for reading as well as an active imagination. An important factor in a child’s development that often gets overlooked is imagination. A child’s imagination is not merely their source of entertainment, it is often their reality and method of reacting to and experiencing the world around them. This is visible especially in kindergartners and preschoolers as their most common form of social interaction involves role-play or pretending. This is suggested in a Journal titled Emotions in Imaginative situations where it states, “Vygotsky (1925/1971) discussed emotion and imagination not as two separate processes but, on the contrary, as the same process” (Fleer et al.) If a child’s ability to express themselves is closely linked to their imagination, one must supply ample stimulants to strengthen that ability. The mind is often called a muscle, and like any other muscle it must be trained in order to keep it strong and healthy. With the emotional appeal of fairy tales and the inspirational powers of illustration, these illustrated stories serve as a perfect exercise for children to develop their emotional literacy in order to maintain healthy relationships in the future.

With the influence illustrated fairy tales have had on countless young minds, it is no wonder that so many artists eventually draw inspiration from these beloved tales. There are so many works of art that greatly benefit from their fairytale roots, however two in particular stand out. Over the Garden Wall, a short animated series created by Patrick McHale, and The Witcher, specifically the video game adaptations based on a series of novels by Andrzej Sapkowski. Over the Garden Wall features two brothers who are seemingly lost in the woods, trying to find their way home. The series originally aired throughout October up to Halloween, and for good reason because it is chock full of spooks and scares. In this lies both the show’s genius and its relation to fairy tales because, considering it is technically a kids show, it pulls no punches with its dark themes and violent insinuations. Examples of this are Adelade the witch who attempts to transform the brothers into her slaves by stuffing their heads with wool or The Beast, a very clear anthropomorphization of death, who feeds on despair of those lost in his woods. While one might think this would deter younger audiences, it is in fact quite the opposite. As has been proven by the Grimm’s fairy tales, children love scary stories. Children often connect with the vulnerability of the protagonists of these tales and are able to experience the harrowing encounters vicariously through the characters. Kids are attracted to this experience as it is a way for them to process fear in a safe setting. It is also this attraction which allowed the show to exist in the first place. Because while the show is quite dark for younger audiences, the precedent set by scary fairy tales and how successful they are with children allowed the show to push through the sterilization of Cartoon Network.

The Witcher series on the other hand is set in a fantasy world, one which is immensely inspired by fairy tales. The story follows Geralt, a monster hunter for hire who travels from place to place trying to earn a living. The monsters and creatures of this world mainly come from folklore and legend, like the Striga, a creature directly inspired by a Roman Zmorski fairytale in which a cannibalistic, monstrous prince is born of an incestuous union between two siblings. The author even creates his own renditions of popular tales such as Beauty and the Beast and The Little Mermaid. These versions are more gritty and offer more mature and realistic morals and interactions. This realism is only amplified by the video game adaptation of the story, as the interactive elements allow the audience to be one step closer to experiencing the world’s first hand. Immersion is something that is often strived for in fairytales, visible through the non specific characters and settings that allow readers to place themselves in the shoes of the characters. Video Games are the logical next step, you are in direct control of the adventure.

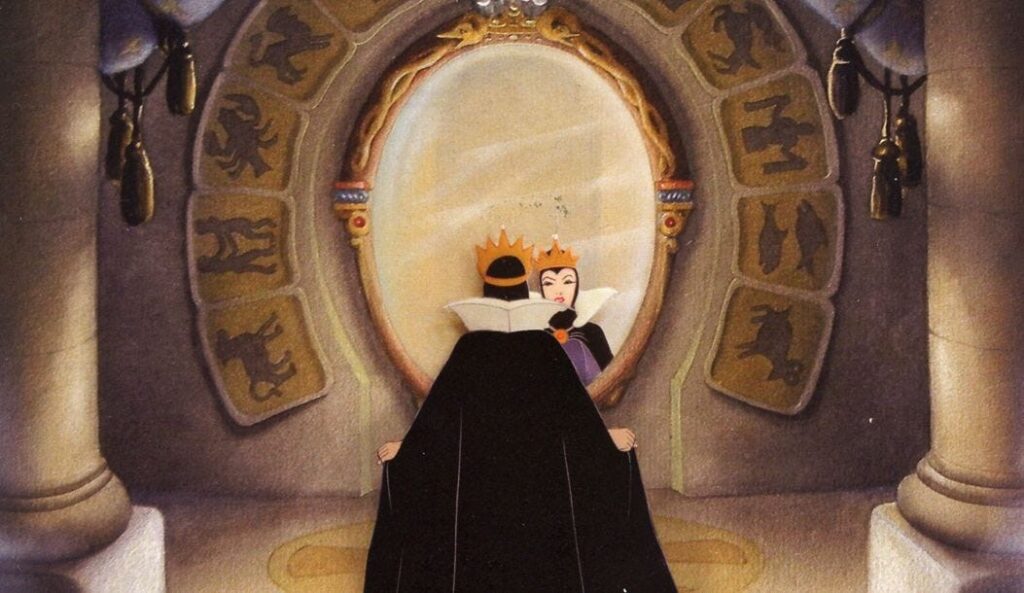

Over The Garden Wall and The Witcher both utilize animation for storytelling, an artform whose success can be directly traced to fairytales. Specifically, Disney’s first full length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, which revolutionized the animation industry. The choice to depict a fairytale was effective for numerous reasons, the first and most important was the previously discussed universality of the tale. Especially during the thirties, every generation was familiar and fond of fairy tales. This made the film appeal to an audience of all ages. For children it would be a more engaging version of the tale they loved, for adults they could be transported back to their childhood years if even for a moment. This began the family movie tradition that is the backbone of animated films to this day. Prior to Snow White, Disney was producing mainly slap-stick style shorts geared towards a younger audience. While these shorts were impressive in regards to the animation, it was not enough to engage a large audience. They lacked the drama and serious tones that Snow White brought to the table. In a recounting of Snow White’s Hollywood premiere, provided by the article Wow, We’ve Got Something Here, the effect of such a tone shift becomes evident:

As the film deepened to darker tones–the Queen transforming into a hag–the atmosphere changed, as though individual audience members were wired together, experiencing the film through a series of shared emotions (Pierce).

Giving the film a serious tone was key to engaging the audience. It created a story with stakes in which the audience could root for the characters. The emotional moments with Snow White were particularly moving thanks to the expressiveness the animation captured. Regular films at the time would have to be carried by the realism of their actors, animation however requires no such realism. The separation from reality ironically allows the audience to be fully absorbed in the moment as they are not thinking about the nuances of the performance. While the film benefited greatly from it’s serious tones, it is also important to mention how its light hearted nature also added to the film’s success. At the time of its release, the country was in the midst of the Great Depression. With the spirits of the masses at an all time low, the whimsical and comedic moments offered by Snow White were the perfect medicine. It not only served as a distraction from the harsh realities families face, but the fairy tale promise of a happily ever after inspired hope. Something desperately needed by many at the time. All in all, Disney undoubtedly revolutionized the animation industry with the success of its film Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. A success that was gained with the aid of the universality, drama, and hope provided by the fairy tale source.

Works Cited

Fleer, Marilyn, and Marie Hammer. “Emotions in Imaginative Situations: The Valued Place of Fairytales for Supporting Emotion Regulation.” Mind, Culture and Activity, vol. 20, no. 3, 2013, pp. 240–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2013.781652.

Greenhoot AF, Beyer AM, Curtis J. More than pretty pictures? How illustrations affect parent-child story reading and children’s story recall. Front Psychol. 2014 Jul 22; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4106274/

Pierce, Todd James. “Wow, We’ve Got Something Here: Ward Kimball and the Making of ‘Snow White.’” New England Review (1990), vol. 37, no. 1, 2016, pp. 123–36, https://doi.org/10.1353/ner.2016.0022.