An Analysis by Julia Pratt

Fairy Tales and Gender Based Violence: An Analysis of Childhood Acculturation by Fairy Tale Motifs

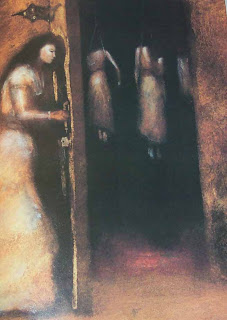

Mahurin, Matt. “The Predator Archetype.” Living in the Forest. July 12, 2013.

Abstract:

Scholars such as Marcia Lieberman, Sandra M. Gilbert, and Susan Gubar have commented on the prominence of the patriarchal voice in fairy tales, but there is less scholarly conversation about the influence that this voice has on the young children who are exposed to the tales. A lack of understanding about the patriarchal narrative in fairy tales poses a danger to the children who absorb the story, as it acculturates children to a society that condones female suppression as valid and expected. Patriarchal acculturation of children poses a dangerous threat to women- a threat that can be seen in steady upwards trends in gender based violence. My research has shown that fairy tales perpetuate patriarchal cycles of abuse in the way that they describe romance and adhere to strict motifs. In particular, depictions of women in fairy tales influence cycles of gender based violence because they perpetuate antiquated depictions of women as helpless, enforce motifs of men as saviors, and have produced a vision of “happily ever after” that convinces young girls that the ideal life is one that is lived under the thumb of a male counterpart. For the purpose of this project I will analyze the romantic relationships between characters in the fairy tales Briar Rose, Snow White, and Bluebeard, and explore how they both support and stray from my thesis that fairy tales promote norms that influence cycles of violence towards women. The investigation of this topic will bring to light some of the subconscious beliefs that fairy tales have ingrained in our minds about how relationships and behaviors should be conducted. This understanding is significant because the commonality of domestic violence, though increasing, is consciously ignored and minimized by greater society. In order to bring an end to gender based violence we must begin to analyze how the cycle itself is created and established, beginning when we are children.

Project 3:

Fairy Tales and Gender Based Violence: An Analysis of Childhood Acculturation by Fairy Tale Motifs

Gender based violence, as defined by the World Health Organization, encompasses any violence that does or could result in physical, sexual, or mental harm to women (WHO, 1). A harrowing 2018 study emerged on the subject of gender based violence which revealed that 1 in 3 women have experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner or loved one (WHO, 1). In the wake of this evidence, vital questions must now be asked and answered: how does our society acculturate children to think about women, and how does said acculturation inform the trends of abuse? Despite their easy reading facade, fairy tales carry dark undertones that acculturate our children to antiquated gender roles that can be very harmful and discriminatory towards women. Fairy tales perpetuate patriarchal cycles of abuse in the way that they adhere to strict motifs and expectations of women. In particular, depictions of women in fairy tales influence cycles of gender based violence because they perpetuate antiquated depictions of women as helpless, enforce motifs of men as saviors, and have produced a vision of “happily ever after” that convinces young girls that the ideal life is one that is lived under the thumb of a male counterpart. We as a society face an urgent call to search ourselves for patriarchal influences that condone such violence and put an end to their circulation. This paper will analyze the romantic relationships of protagonists in the fairy tales Briar Rose, Snow White, and Bluebeard, and explore how the descriptions of these relationships perpetuate norms of patriarchal abuse.

The first tale discussed in this analysis will be Briar Rose. This tale is a reiteration of Sleeping Beauty, and is one of the many hundreds of tales told by the Brothers Grimm. In this version of the tale, a king and queen give birth to a beautiful daughter, and invite the entire kingdom to a great feast so that the Wise Women of the land can bless their child with many good qualities (Grimm, 130). However, they do not have enough golden plates for all thirteen wise women, and so they decide to only invite twelve (Grimm, 131). The thirteenth crashes the celebration in anger and disrupts the ceremony, placing a curse on the child that on her fifteenth birthday she will prick her finger on a spindle and die (Grimm, 131). Luckily, the twelfth fairy had not yet blessed the child, and so she changes the curse so that when the child pricks her finger she will not die, but instead fall into a 100 year long slumber (Grimm, 131). All of this comes to pass, and the entire kingdom falls asleep, only to be rescued by a wandering prince 100 years later on the last day of the spell’s term (Grimm, 132). The prince kisses Briar Rose’s lips, she wakes up along with the rest of the palace, is promptly engaged to him, and they all live happily ever after (Grimm, 133).

The tale of Briar Rose perpetuates the stereotype of women as being helpless in the way that it describes her clueless character. First, it is important to examine the positive female attributes that the Wise Women bestowed upon Briar Rose: “one conferred virtue on her, a second gave her beauty, a third wealth, and on it went until the girl had everything in the world she could ever want,” (Grimm, 131). These are characteristics that are often positively attributed to women in fairy tales, and all of them serve to capture the attention of men. Scholars Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gumar remark that attributes such as these dismiss female autonomy and position women lower than the male characters in terms of sense and intellect, as male characters are rarely simply reduced down to their looks in the same way that female characters are (Gilbert, 390). Aside from this, Briar Rose’s character remains clueless to the events taking place around her, and she is clearly unaware even at age fifteen of the curse that has been placed on her. This suggests that no one told her of her fate, meaning that she was not entrusted with any sort of personal responsibility by her parents to protect herself. Even nuances like this leave young readers to assume that she was not entrusted with her own destiny, and serve to condition children to believe that she was not worthy of control.

Male heroism underlines this entire tale of a spellbound young woman. A wandering prince steps on her sleeping spell, and after a non-consensual kiss between him and Briar Rose, the day is reported to have been saved. Marcia Lieberman’s renowned article “Some Day My Prince Will Come” speaks on this phenomenon in which fairy tales condition young girls to wait for a male prince to swoop in and provide a happily ever after for them, and her assertion holds true in Briar Rose as well. Yet, perhaps the most irresponsible part of this narrative is that Briar Rose was about to be freed from her spell not by the kiss of a prince, but by time: “It so happened that the period of one hundred years had just ended, and the day on which Briar Rose was to awaken had arrived,” (Grimm, 132). This princess had served her due time and was about to be freed by no one other than herself, and yet the prince’s non-consensual interference earns him ample praise as well as her hand in marriage. This story supports the patriarchal norm that men can do whatever they want to women’s bodies and circumstances, regardless of whether or not they are asked to, and still be praised. This message teaches young girls in turn that their position is as quiet and helpless damsels who are in need of a male savior- a mindset which no doubt has a hand in the perpetuation of gender based violence against women.

The second tale discussed in this analysis will be Snow White. In this Brothers Grimm rendition, a queen wishes for a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of a window frame (Grimm, 95). She gives birth to this child, and promptly passes away, leaving her husband to remarry to a beautiful yet proud woman (Grimm, 95). While conversing with her magic mirror, Snow White’s stepmother finds out that she has been surpassed in beauty by the child, leading her to send a huntsman to murder Snow White in the woods (Grimm, 96). He lets her escape however, drawn to pity by Snow White’s beauty, and the girl runs until she finds a group of friendly dwarves who agree to provide her shelter so long as she cleans and cooks for them, to which she agrees (Grimm, 98). Not long after, her stepmother’s mirror alerts the woman to Snow White’s existence with the dwarves, and so she sets out three times to kill her (Grimm, 98). She nearly succeeds twice, but both times the dwarves save her (Grimm, 99). On the third attempt Snow White falls asleep as if dead with a piece of poison apple stuck in her throat, and it is only after her assumed corpse is given by the dwarves to a wandering prince as a gift, that the apple is jolted from her throat and she breathes again (Grimm, 101). At this turn of events, she and the prince marry, the queen is forced to dance to death in red hot iron shoes, and they all live happily ever after (Grimm, 102).

The tale of Snow White is also an active perpetuator of patriarchal violence against women because it not only depicts women as helpless and in need of a male savior as in Briar Rose, but it also enforces the idea that a woman’s “happily ever after” is found by living a subservient life to men. While scholars Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar have done fascinating research centered on the ways that the patriarchal voice in this story pits Snow White and her stepmother against each other to compete for the beauty and status dictated by men (Gilbert and Gubar, 389), this analysis will focus solely on Snow White’s individual character and her relationship to the surrounding male characters in the story. Snow White is described as being exceedingly helpless, with the Grimm Brothers utilizing words such as “unsuspecting” and “foolish” to paint a picture of her character (Grimm, 101). While her intellect and judgement is severely lacking, there is ample description of her beauty, graciousness, and tenderness (Grimm, 101), all of which stress to young readers that physical attributes are desirable for women to strive for, while intellect and common sense are not.

Similarly to Briar Rose, the tale of Snow White also glorifies male heroism not only in its descriptions of the dwarves’s valiant efforts to save Snow White, but also in the prince’s mishap with her casket that credits him with saving her life. Each time that Snow White falls victim to her own foolishness or naivete, the dwarves come in and save her, so enamored by her beauty that they cannot bear to let her die (Grimm, 101). When they are unable to be heroic themselves and revive her, instead of mourning her lost life and moving on, they instead gift her corpse to a complete stranger on the promise that he will “honor and cherish her as if she were his beloved,” (Grimm, 101). After Snow White is accidentally awakened she is immediately proposed to by this prince, who claims to “love her more than anything else on Earth,” (Grimm, 101). In this tale, the same theme arises as in Briar Rose where a rudely awakened woman finds herself engaged to a man she doesn’t know yet who claims to have saved her, and it is expected for her to take it in stride with beauty and grace. The fact that Snow White develops “tender feelings” (Grimm, 101) for this prince on the moment of her awakening not only sends a message to young women that they owe men their lives and bodies for any action of kindness shown to them, but also that “happily ever after” is only found after becoming engaged and entering under her husband’s jurisdiction. The voice in this tale therefore perpetuates cycles of gender based violence because it describes an ideal world in which women have no control over their intellect, decisions, or destinies- an ideology that ingrains in both young boys and girls alike that their gender roles are set in stone and absolute.

The third and final tale in this analysis will be Bluebeard. This tale, narrated by Charles Perrault, describes the story of a young woman who marries an extremely rich man with a blue beard. She at first thinks him hideous for his beard and is suspicious about the disappearances of his previous wives, but after enjoying a week-long party thrown at his mansion, she finally accepts his proposal and they are married (Perrault, 189). After some time, Bluebeard has to leave on business and gives her the keys to every room, warning her to not enter the smallest one lest she face the dire consequences of her disobedience (Perrault, 189). She promises not to open the door, but is overcome by curiosity and does so anyway, only to discover a blood bathed room filled with the corpses of his previous wives (Perrault, 190). In her shock she drops the key, which is then covered in a blood stain that cannot be removed (Perrault, 190). Bluebeard returns home unexpectedly that night and confirms her disobedience after seeing the stain on the key, and he gives her a few moments to say her prayers before he kills her as punishment (Perrault, 191). Before he can do so however, her brothers arrive in the knick of time and save her from her fate by killing Bluebeard themselves (Perrault, 192). She then inherits his entire fortune, remarries, and lives happily ever after (Perrault, 192).

This tale, in the same fashion as the first two, perpetuates the idea that women are helpless and reliant on male heroes to save them from their mishaps. Not only is Bluebeard’s wife helpless to save herself from his wrath, but she is also helpless to control her own curiosity at his orders to not look in the room. Perrault states that: “she reflected on the harm that might come her way for being disobedient..but the temptation was so great that she was unable to resist,” (Perrault, 190). This quote normalizes the misogynistic idea that women are not in control of their decisions or impulses- a notion which, for centuries, has fueled the perpetuation of patriarchal society. This tale could have been one which condemned Bluebeard’s- and consequently the patriarchy’s- violent and unacceptable actions towards his wife, and could have endeavored to showcase a young female character who saves herself and stars as the heroine in her own story. Instead, not only does Perrault never condemn the immorality of Bluebeard’s murderous tendencies, but he also shifts all praise for the happy ending to his wife’s valiant brothers, crediting them for saving their sister’s life by murdering her husband. This perspective yet again heaps glory onto male characters who arrive at the last minute to save the damsel in distress, and it also acculturates young boys to believe that righteous anger is justifiably expressed by violence- a belief that perpetrates much of the domestic gender based violence against women today (WHO, 1).

Bluebeard does not just glorify male heroism by having the woman’s brothers save her at the end of the day, nor does it just perpetuate the idea that women are helpless, but most terrifyingly of all, through Bluebeard and his wife’s conversation, it teaches young men that it is just to harm women for not being obedient to their desires. Perrault presents a dangerously misogynistic moral at the end of this story which can be reduced to the statement: “women succumb to the fleeting pleasures of curiosity and pay the price for it,” (Perrault, 192). There is no moment of respect or remembrance in honor of Bluebeard’s previous murdered wives, and they are therefore quickly forgotten. Their stories are drowned out by the fast-forwarded ending of the tale, in which Bluebeard’s surviving wife gives away her entire inherited (and dare it be said, earned through suffering?) fortune on commissions to her brothers and marriages for her sister and herself (Perrault, 192). Once again, the story ends with a marriage between the main female character and a “worthy man” (Perrault, 192), further instilling into children that the only thing a woman needs to be happy is a man to control her every move. These three tales influence cycles of gender based violence because they perpetuate antiquated depictions of women as helpless, enforce motifs of men as saviors, and acculturate both young girls and boys alike to believe that “happily ever after” is lived under the thumb of a male counterpart. The tales Briar Rose, Snow White, and Bluebeard all feature helpless female characters who eventually meet men who have little to no part in their liberation yet take all the credit for it, and each of these women are successfully married off to their male saviors and live happily ever after. For centuries these tales have been told to children as bedtime stories and in gatherings, and through their communication have successfully perpetuated the patriarchal voices that they uphold. The consequences of the unaltered and uncondemned broadcasting of the patriarchal voice are harrowing increases in gender based violence against women, a lack of self esteem and self belief in young women, and a pervasive cultural idea that women are destined to be subservient to men (Lieberman, 384). These tales acculturate both young boys and young girls to see the world through a patriarchal lens, and until their role in popular culture is reevaluated, we will continue to face the same cycles of gender based violence against women.

Works Cited:

Brothers Grimm. “Briar Rose.” The Classic Fairy Tales: Second

Norton Critical Edition, edited by Maria Tartar, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

130-133.

Brothers Grimm. “Snow White.” The Classic Fairy Tales: Second

Norton Critical Edition, edited by Maria Tartar, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017. 95-102.

Gilbert, Sandra M.; Gubar, Susan. “Snow White and Her Wicked Stepmother.” The Classic Fairy

Tales: Second Norton Critical Edition, edited by Maria Tartar, W.W. Norton & Company,

2017. 387-393.

Lieberman, Marcia R. “‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the

Fairy Tale.” College English, vol. 34, no. 3, 1972, pp. 383–395. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/375142. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021.

Perrault, Charles. “Bluebeard.” The Classic Fairy Tales: Second

Norton Critical Edition, edited by Maria Tartar, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

188-193.

“Violence against women.” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, March 9, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.