By June Lee

Female villains have always been an exciting subject in literature and general theater. The female antagonists’ character development and manipulation strategies, ranging from evil stepmothers in fairy tales to femme fatales in Shakespearean plays, have continued to draw attention throughout the centuries. However, much depends on what is shown through different types of media. This paper examines the effect of media on the interpretation of “Hansel and Gretel” and “Macbeth.” Both stories involve close adversaries who manipulate one another. Nonetheless, they differ in their communication medium – written literature or live stage performance. This analysis will clarify how women are depicted as villains depending on the medium used. It will also contribute to understanding whether there are any specific relations between narratology, gender, and its role within interpretative practice concerning literature and drama.

The antagonist of the fairy tale, “Hansel and Gretel,” is an old, wicked witch who deceives and manipulates the children in order to devour them. This story mainly revolves around the ordeal experienced by these young ones. From this device, the readers are mainly meant to identify with the kids and see nothing in the witch but pure evil. In line with this description by the Brothers Grimm, “Just then the door opened, and a very old woman walking on crutches came out” (Brothers 56). Her unnatural appearance is described initially through this image of an older adult who is physically disabled and later enhanced by her tricks and malicious plans. From the story’s detail, one can see how the narrative’s perspective determines what is considered evil. We see her feeding, locking up, and attempting to cook Hansel, whilst overworking little Gretel—all from their point of view, increasing the terror and demonstrating her wickedness (Brothers 63-75). Such kind characters who pretend to offer help but harm you are familiar in fairy tales because they teach children a moral lesson about strangers.

On the contrary, Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” is a much more complicated and exciting evil character. This character is considered “witchlike” similarly in the children’s story of Hansel and Gretel. However, this woman cannot be compared with a simple witch because aside from being just wicked, she also has to deal with her deep innermost thoughts: the thought about what she wants and what follows after it. Right away, it becomes clear that she plans something – “Glamis thou art, and Cawdor, and shalt be/ What thou art promised’ (Shakespeare 1. 5). Her manipulation of Macbeth is neither passive nor innocent but very active, well-planned, and leading to his downfall.

Throughout Shakespeare’s narrative, Lady Macbeth becomes less malicious as she begins to go mad from grief over her many sins. The complexity portrayed here typifies Shakespeare’s morally convoluted world, an environment in which villains are not simply wicked but motivated by pride, ambition, and terror inherent in every person. There are two tales that both have female oppositions who use manipulation to achieve their goals. However, the character of Lady Macbeth is depicted in a complex manner, considering the effects of her drive and manipulation while an outright evil witch is portrayed “Hansel and Gretel.”

The particular form of media employed directly affects how readers or viewers portray and perceive these characters. For instance, within the written story of “Hansel and Gretel,” readers see things only from one side, forming an image of the witch without being offered reasons for or understanding her behavior. On the other hand, the theatrical account of Macbeth reveals a different side to events through navigating the speaking and acting characters of Lady Macbeth and others, with some complexity portraying motivation that leads to the gradual downfall on her part. Comparing these textual portrayals of female villains reveals that the nature of the work—conventional literature compared to stage production—has dramatically impacted how we interpret their persona and lies, insulting simpler interpretations in the former case.

Scholars have examined how female criminals are depicted in literature, especially regarding how and reinforces reading against such backdrops. In her thesis on witches in Literature, Haesler observes that witches are usually described as “simple evil old women” in written texts (Haesler 29). The conventional picture derived from this is inherently limited since it follows some guidelines of the patriarchy, but not all of them, for it does not delve into the characters’ thoughts and motivations.This point by Haesler is evident in the witch’s character in “Hansel and Gretel.” It was noted before that she appears like your typical bad guy who is very controlling and manipulates others while always showing her true colors and evil plans for them both. Unlike Lady Macbeth, this portrayal results primarily from a single viewpoint the text adopts within a conventional fairytale framework.

Theater provides an avenue through which one can know the complexity of a character since, in drama, sometimes a variety of different things are done or said by various people (McCall 187). A good case study for this is the character of Lady Macbeth. McCall’s paper analyzes the reasons behind this statement. By analyzing other witches first before comparing them to Lady Macbeth, one can conclude that her evil nature encompasses many factors, such as relentless determination towards her goals, which causes so much harm or even death, always feeling troubled deep down inside because she cannot control everything like she used to, and finally, tragedy occurs.

However, even though she is evil, some scholars view Lady Macbeth’s character is that of a strong feminist. The character is an evil woman full of ambition and intelligence, contradicting the conventional gender theories about Macbeth or the stereotype of women only utilizing sex appeal to achieve their goals. From these scholarly opinions on other female villains, we can see how stories have been influenced by what we see or read about women and their mischief in media forms.

The witch is portrayed as entirely wicked in “Hansel and Gretel” because of the simple narrative point of view adopted in most children’s literature and societal norms; however, this could not work with theatre script, which took another approach into considering several issues concerning motivation and conflicts within Lady Macbeth. It illustrates that different forms of media can significantly shape how people perceive and analyze female villains’ nature, whether they are considered evil characters or pitied for the tragic fate they bring upon themselves. Thus, analyzing the primary written materials alongside some additional guidelines reveals one crucial fact – women evildoers cannot be similarly seen in all classical books or plays due to formatting in literature.

Apart from analyzing written materials closely and integrating other authors’ opinions, examining visual media may also show the impact of such media on the interpretation of female villains in “Hansel and Gretel” and “Macbeth” primary texts.

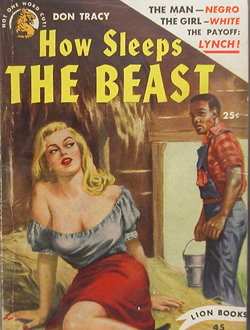

Diverse portrayals become apparent when analyzing different pictures portraying the evil female characters in these stories. For example, in most illustrated versions of “Hansel and Gretel,” the witch appears as a repulsive old woman with highly emphasized ugly characteristics that create terror and disgust and emphasize her as an utterly lousy character. These images reinforce how the text presents the identity of the witch, like every other, who is feared because of her difference – seen mainly through the innocent eyes of some children. For instance, an animated version would show the witch “as a scary old hag, with her nose covered in warts and heinous look on her face” (Brothers Grimm, Animated Film). This standard portrayal strengthens the idea that witches are pure forms of evil that lack any positive attributes.

However, the way Lady Macbeth appears in different theatre performances tells a different story altogether because it is not easy to determine the character of Lady Macbeth due to the immoral nature found in most of Shakespeare’s work. Liverpool Everyman Playhouse’s production portrays her as an intelligent temptress, showing hints of royalty behind an attire that spells sophistication. This portrayal is inconsistent with other productions, where Lady Macbeth comes off as callous and insensitive. The costume, lighting, and setting details bring out another aspect of change in character whereby she changes from being just ambitious like any other woman into someone now haunted by guilt and going insane with madness. For example, when she manipulates Macbeth in one of the scenes, her courage and ambition are brought up through intense soliloquy while highlighting the emotional chores she engages in herself. Stage-wise, it portrays how cunning she can be (Digital Theatre+, “Macbeth,” Act 1, Scene 7).

In addition, the physicality depicted when Lady Macbeth is in action brings out interesting details on her state of mind and motivation that otherwise would have given a straightforward picture. For example, in one production, there were long pauses, grimaces, and trembling fits, in this case rightly taken to imply that she is mad with guilt and has come to pieces (Digital Theatre+, “Macbeth”, Act 5, Scene 1).

Visual media dramatically influences people’s views and opinions about evil women characters from books or plays. It depends on what kind of media was taken – did they prefer stills from a comic book about “Hansel Gretel,” or maybe they used special effects during their work on “Macbeth” which could not convey everything by words alone but provided additional information for better understanding of the role? All these differences depend on specific properties inherent to the mediums through which female villains are represented and determine complex audience reactions ranging from fear/hatred towards the witch character in “Hansel and Gretel” to admiration/pity for Lady Macbeth herself.

In conclusion, the portrayal of evil women in drama and fiction depends much upon what kind of media is used. This essay has investigated how different factors such as narrative mode, stagecraft, and iconography affect our understanding when comparing two classic texts – “Hansel and Gretel” and “Macbeth”. It follows that written literature most times uses a very plain linear female villain character. Stage performances on the other hand can avail to the development of complex female villains. Additionally, this is enhanced by visual media that reveal more about these characters’ nature through numerous symbolic representations. These results are important for understanding the ways through which media constructs gender and morality in literature and art. In conclusion, one must take into account the communication channel employed in a given story so as to understand and judge correctly the role and character of female villains therein depicted.

Works Cited

Brothers Grimm. Hansel and Gretel. BompaCrazy. Com, 1975.

Brewer, David. “Macbeth.” Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse Theatres, Everyman&Playhouse, 11 June 2011, www.everymanplayhouse.com/whats-on/macbeth-2011.

Digital Theatre+. “Macbeth.” Act 1, Scene 7, Act 5, Scene 1. Digital Theatre+, 2018. https://education.digitaltheatreplus.com/he-explore-digital-theatre/shakespeare-early-modern

Haesler, Jóna Kristín Óttarsdóttir. Witches in Literature. The changes of the witch figure throughout history. Diss. 2021.

McCall, Jessica. Monsters and Villains of Movies and Literature. ABC-CLIO, 2019.

Merino Calle, Beatriz. “Disney Witches and Feminism.” The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairytale and Fantasy Past. Ed. Tison Pugh. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020. 11-23.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth: A Tragedy. Mathews and Leigh, 1807.