By: John Omiya

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales.”

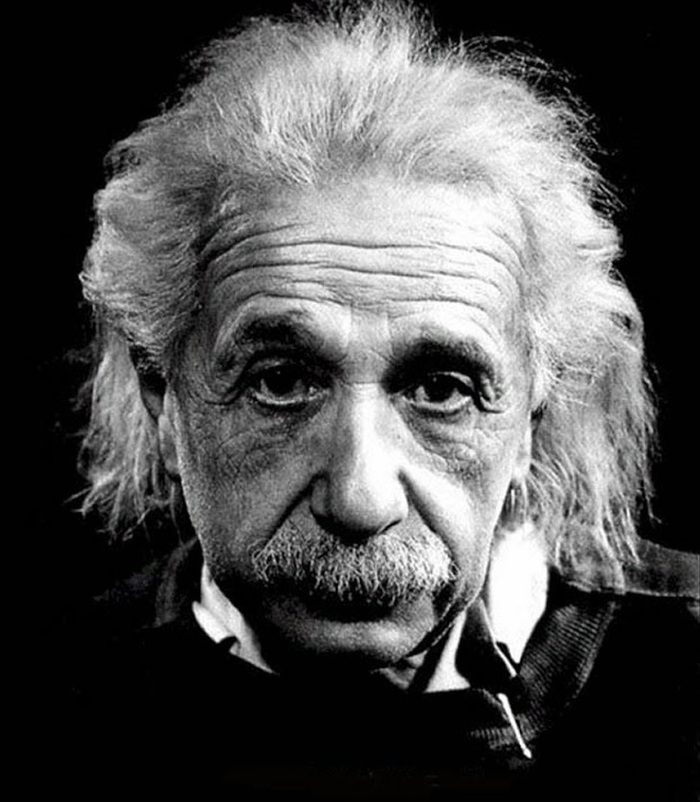

Albert Einstein

Fairy tales are a cherished part of childhood for many people. These stories, often featuring magic and fantastical elements, have been passed down through generations and have become a beloved part of many cultural traditions. Aside from their ability to entertain and captivate young audiences, fairy tales may also have a profound effect on neurological development. Einstein believed that these fictitious tales play a pragmatic role in the neural development of children. A study conducted in Iran supports Einstein’s hypothesis, indicating statistically significant data regarding a positive direct correlation between intelligence and childhood fairy tales (Sajedi et al., 2018). Another study in Greece indicated the same data, with children preferring classical fairy tales over modern ones (Tsitsani et al., 2011). Einstein’s hypothesis about fairy tales and intellect is plausible because the trends of these studies indicate a deeply rooted correlation between neurological development and characteristics of classical fairy tales.

A study conducted in 2019 revealed differences between expository and narrative genres in brain development (Aboud et al., 2019). The study utilized 62 participants between the ages of 8 and 10. The children read a total of 5 narrative passages and 5 expository passages that met adequate statistical parameters in terms of difficulty and length. Between each read, the children were scanned by MRI to detect regions of brain activation. The article indicated that the fairy tale genre significantly aids in the development of the angular gyrus, superior temporal sulcus, lingual gyrus, and temporal lobe in comparison to the expository genre.

The angular gyrus lies in the rear region of the posterior parietal lobe and plays a significant role in determining the meaning of visually perceived words, memory retrieval, and attention. The visual perception of words develops as a direct result of reading fairy tales, leading to greater literacy. Some fairy tales, such as “The Three Little Pigs” offer repetitive, rhythmic, patterned language, such as “little pig, little pig, let me in,” or “I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house down” (Jacobs, 1890). This phonological characteristic of some classic fairy tales contributes to language development because it offers a unique, recognizable pattern to words. Further supporting this claim is a journal from 2021 that indicates the development of these phonological skills demonstrates a strong correlation to early reading and writing development (Milankov et al., 2021). Fairy tales, therefore, boost intelligence because they greatly aid in the acquisition of developmental literary skills. Memory retrieval and attention, on the other hand, work synergistically, with attention generating sensory queues for memory traces (engrams) to be stored within the mind. The imagery oftentimes described in these magical tales requires its reader to utilize sensory imagination, amplifying the necessity for attention. Subsequent reading of the same fairy tale oftentimes leads to the same image generation, aiding in memory retrieval. Fairy tales such as the Grimm’s “Snow White” state, “…white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as ebony…” to aid in the visualization of the character (Tatar 95). This example doubles down on its application of imagery, employing visual aids such as snow and blood to further drive specificity. Further evidence to support the linkage between narrative genres and greater proficiency in memory retrieval is shown in The Impact of Pleasure of Reading on Academic Success which provides sufficient evidence for a positive correlation between reading and comprehension (Cupp et al., 1990). Finally, the angular gyrus deals with the processing of social queues, often regarded as the theory of mind.

The lingual gyrus primarily deals with basic and higher-level visual processes. The visual processing unit of the lingual gyrus deals with the recognition and naming of different visual stimuli, such as letters and words. Consequentially, the lingual gyrus plays a crucial role in the development of literacy. Reading fairy tales aids in the development of the lingual gyrus because fairy tales present literary material with unique characteristics such as phonological patterns, resulting in increasing levels of literacy. The narrative nature of fairy tales also entails the usage of common or everyday objects and actions, allowing for the development of foundational, frequently used words, further boosting literary and intellectual development. It is also important to note that the lingual gyrus plays a secondary role in analyzing logical conditions. While the correlation between reading fictional fairy tales and the development of logical conditions seems counter-intuitive, fairy tales present a unique landscape for this process to develop. Because fairy tales utilize Propp functions as a scaffold to build their narrative, each fairy tale follows these functions to an extent, leading to a logical, patterned, sequence of events. It is no wonder, therefore, why fairy tales contribute to higher levels of development of the lingual gyrus. The temporal lobe works synergistically with the lingual gyrus by forming a bridge between literacy and meaning.

The temporal lobe deals primarily with language comprehension and emotion association. Within the temporal lobe lies the hippocampus, a structure of the brain that is crucial for all memory formation, with its surrounding structures required for memory storage. Fairytales are often either read or told, each contributing a unique stimulus to the temporal lobe. Auditory and visual memory are processed in separate areas, indicating that fairy tales play a twofold role in processing sensory development. Unlike the lingual gyrus, the temporal lobe plays a crucial role in both auditory and visual language recognition. The temporal lobe plays an additional role in creating bridges between memory and emotion, relaying complex ideas to visual and auditory stimuli. This linkage promotes greater memory formation and retainment because the incorporation of an emotional aspect to memories imparts greater interconnectedness of hippocampal neurons. For example, “Little Red Riding Hood” evokes emotions of fear and terror of the bestial nature of wolves, whilst “The Little Mermaid” evokes emotions of tragic pity. These emotions assist in the recollection of the entire story, giving additional context to the fairy tale. Furthermore, emotional development is a crucial part of developing social skills that contribute to intelligence.

The final region of the brain that is stimulated and developed to a greater extent by fairy tales is the superior temporal sulcus. The superior temporal sulcus deals primarily with spoken language processing and social processing. Phenomes, words, sentences, and phonological cues stimulate the superior temporal sulcus. Fairy tales include all these cues, oftentimes averaging a greater quantity of phonological cues compared to expository writing. Fairy tales, therefore, play a specialized role in language processing because they are powerful stimuli that assist in the development of fundamental language processing skills. Social processing, on the other hand, presents a much more fascinating implication of fairy tales because the theory of mind is largely involved in this process. The theory of the mind describes the capacity of a person to understand another person’s mental state. Given that fairy tales are synthesized the human mind and tell stories about relatable protagonists, they allow us to peer into the minds of both the characters and the writers themselves. This characteristic of fairy tales and many other forms of narrative literature offers a special stimulus for the development of the theory of mind, leading to higher levels of intelligence because the theory of mind is required for successful social interactions.

With the regions of the brain that are especially stimulated and developed by fairy tales established, it would be appropriate to turn and apply this hypothesis to “Little Red Riding Hood” because the study in Greece supporting Einstein’s hypothesis indicated that the classical version of this tale was preferred among most children (Tsitsani et al., 2011). This study introduces the perspective of Bruno Bettelheim, an Austrian-born psychologist of the 20th century, to explain why children would prefer the harsh, classical version of “Little Red Riding Hood.” The study explores ideas from Bettelheim’s “The Uses of Enchantment” to explain that fairy tales are a particularly special genre of literature that exploits characteristics of the developing mind, such as animism, to provide coping mechanisms for children’s inner stresses and anxieties (Bettelheim, 2010). Facts use fiction as a disguise, much like the wolf of “Little Red Riding Hood,” to lower the “guard” of children, promoting a more effective delivery of the message. Bettelheim explains that the maturity of a child’s mind is not ready to handle the utterly complex structure of society or the sciences, but fairy tales provide the same message through magical means that are more understandable to the child’s mind. The magic that fairy tales possess, therefore, is a necessary quality for children to

Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood” stimulates all regions of the brain previously explained. “Little Red Riding Hood” incorporates phonological components during the final exchange between Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf disguised as her grandmother. The exchange between the two characters involves many single-syllable words, such as “Grandmother, what big ears you have!” or “Grandmother, what big eyes you have!” that isolate the phonemes (individual sounds) of words (Tatar 17). This characteristic of “Little Red Riding Hood” aids in the development of the angular gyrus and lingual gyrus because the single syllable repetition acts as a powerful stimulus for word recognition. Word recognition, in turn, promotes higher levels of intelligence because word recognition is a foundational component of literacy. “Little Red Riding Hood” stimulates language processing of the superior temporal sulcus through hidden innuendos, such as the promiscuous nature of the exchange between Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf at the end of the tale. There are other hidden innuendos such as Little Red Riding Hood having a “good time” on the longer path. Detection of these innuendos requires higher forms of language processing because they require the reader to derive interpretations beyond the surface of the text. The superior temporal sulcus is also stimulated through the social commentary of the fairy tale. The wolf of “Little Red Riding Hood” symbolizes the predatory nature of certain men, providing information that grows the theory of mind. At the same time, the animism of the wolf creates an understandable medium for children, as Bettelheim describes. “Little Red Riding Hood” demonstrates its potential in intellectual development because its linguistic characteristics and content provide a stimulus for neural development while maintaining an interesting story for children.

While it is fascinating to see the complex relationship between fairy tales and neurological development, it should be no wonder why the two are deeply interconnected. Fairy tales are the product of the immensely complex human mind; therefore, fairy tales tell a story about human nature. As organisms that have benefited greatly from intellectual evolution, humans have developed a method that allows us to develop our highly advanced linguistic abilities and sociability. Fairy tales have maintained continuity over the past millennia because they describe human nature, which will exist as long as humans do.

Works Cited:

Bettelheim, B. (2010). The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales. VINTAGE Books.

Cupp, G. M., Dyer, P. A., Morrison, T. F., & Tracz, S. M. (1990). The relationship between Pleasure reading, textbook reading & academic success. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 23(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.1990.10849955

Jacobs J, English Fairy Tales (London: David Nutt, 1890), no. 14, pp. 68-72.

Milankov, V., Golubović, S., Krstić, T., & Golubović, Š. (2021). Phonological awareness as the foundation of reading acquisition in students reading in transparent orthography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105440

Sajedi, F., Habibi, E., Hatamizadeh, N., Shahshahanipour, S., & Malek Afzali, H. (2018). Early storybook reading and childhood development: A cross-sectional study in Iran. F1000Research, 7, 411. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.14078.1

Tatar, M. (2017). The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, criticism. W.W. Norton et Company.

Tsitsani, P., Psyllidou, S., Batzios, S. P., Livas, S., Ouranos, M., & Cassimos, D. (2011). Fairy tales: A compass for children’s healthy development – a qualitative study in a greek island. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(2), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01216.x