Rapunzel and Beauty Standards

Since the 1400s, skin color and physical appearance have been used as points of justification for harm and oppression. White-skinned Europeans labeled themselves as saviors, and having white skin became associated with the values of civility, justice, and good. This process of course labeled Black people, indigenous peoples, and people of color as savage as well as lesser than, on the basis that their skin wasn’t white. In other words, white people and the appearances of white people became the accepted standard. One way in which this system mainly exhibited itself was through the concept of beauty. White women became the direct definition of beauty, on the basis that they were white and possessed European features—which white men were attracted to. On the other hand, Black women were deemed ugly as well as forced to aspire to have the appearance of white women. Black women were harmed, as well as harmed themselves, because their beauty did not fit into these racialized standards. Even today, this system of beauty still prevails and one way it has asserted itself is through fairytales like Rapunzel. Rapunzel informs us that beauty standards uphold white supremacy by idealizing white womanhood through representations of gold hair. These standards are harmful to Black women because they damage Black women’s self-perception and undermine their beauty.

Both the Grimm’s version and Friedrich Schulz’s version of Rapunzel tell us that Rapunzel’s long blonde hair is what makes her beautiful. In the Grimm’s version it states, “Rapunzel grew to be the most beautiful child under the sun…Rapunzel’s hair was long and radiant, fine as spun gold” (Grimm 490). It is emphasized here that her hair was so beautiful that it could be equated to gold. Another thing we can take from this quote is the part where it states that she was the most beautiful. We can safely infer that her hair is what made her “the most beautiful child under the sun”; in other words, she is so beautiful because she possesses this hair— realistically because she is a white woman. It is widely known that white women are the main beneficiaries of natural blonde hair. In terms of the beauty that is promoted within this tale, any woman that had hair that wasn’t like Rapunzel’s would be deemed ugly. Friedrich Schulz’s version says something similar when mentioning Rapunzel’s hair. The tale reads, “Rapunzel’s hair was the most beautiful part of her. It was thirty yards long, and she did not mind having such heavy hair. It was blond just like the finest gold and woven into braids and tied with beautiful ribbons” (Schulz 486). Here also, we see the emphasis that is placed on her blonde hair: it is the one thing that truly makes her “beautiful”. Another thing which is emphasized in both the Grimm’s version and Schulz’s version is the length of Rapunzel’s hair. Both make sure to include this detail when discussing how beautiful the hair made her. The length is praised just as the blondeness is praised; short hair or shorter hairstyles would also be deemed ugly by this standard. In idolizing Rapunzel’s beauty, through her long and blonde hair, the tale essentially racializes the idea of beauty. Women who don’t naturally possess this type of hair, Black women to be specific, are considered ugly by this Rapunzel standard. The beauty of their hair is negated because it does not fit the standard.

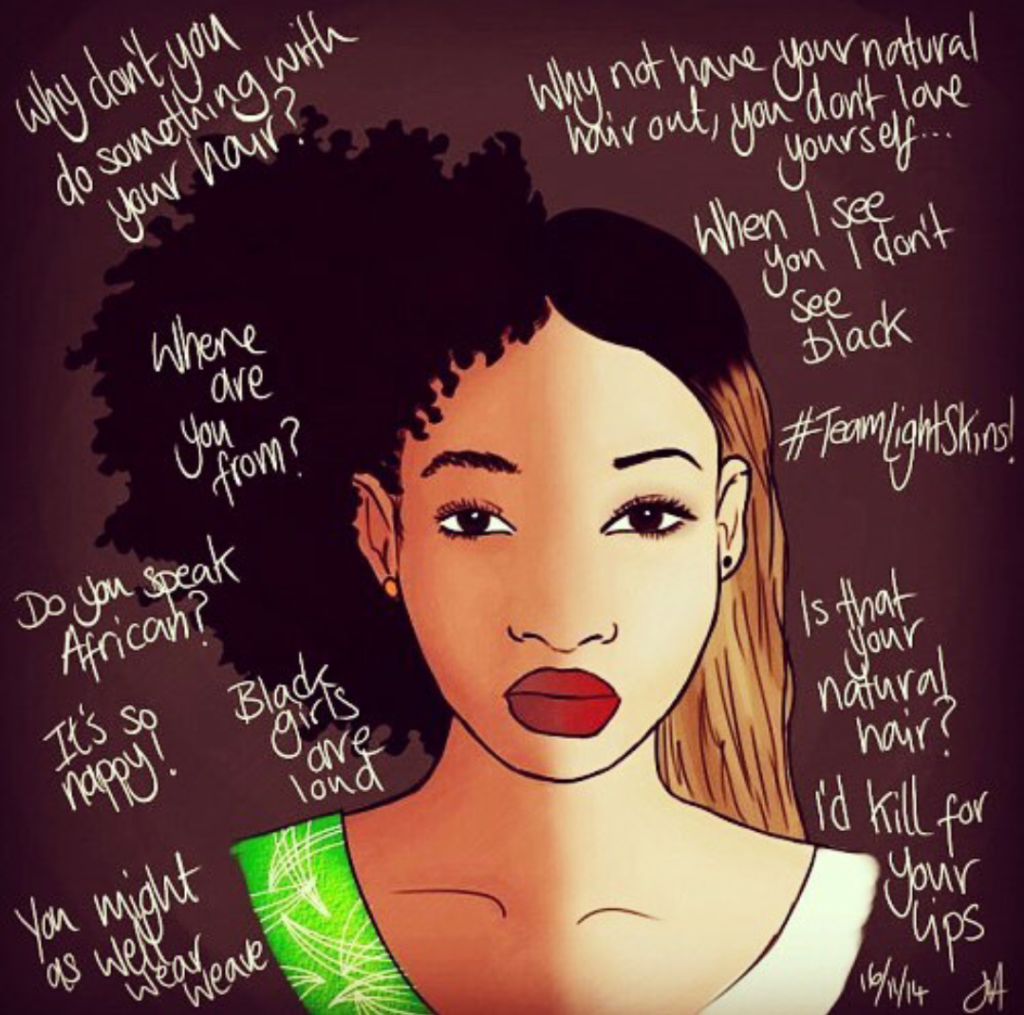

Beauty standards harm Black women by damaging their self-perception. For example, in an article titled “Hair as Race: Why ‘Good Hair’ May be Bad for Black Females”, author Cynthia L. Robinson shares how many Black women feel about their hair. In the article, one of the women that Robinson is interviewing states, “And [my sister] said the same thing. She would rather have white people’s hair. It’s just so much easier…It’s not anything against our color. It’s just that, I just don’t like Black hair. Because for me personally, when I do press it, it doesn’t stay pressed. It just kinks right back up” (Robinson 369). Although the Black woman being interviewed mentions that she dislikes her hair because of how difficult it is to manage, we can still see how much she has internalized beauty standards. She explicitly says, “It’s just that, I just don’t like Black hair”, while she has Black hair herself. She is unappreciative of her own hair because she idolizes how easy it is for white women to manage white hair and have their hairstyles deemed acceptable by society: she wishes she had the hair of white women. Along with the idea of hair, beauty standards also encompass skin color. Beauty standards form a skin color hierarchy in which white woman are placed at the top, and all other races exist beneath them: Black women are at the bottom, because they have Black skin. In an article titled, “The Beauty Ideal: The Effects of European Standards of Beauty on Black Women” author, Susan L. Bryant talks about the effects that this hierarchy has on Black women. She states, “Black women who do not meet the established standards of European beauty are more likely to be unemployed than those who have more of the preferred European physical characteristics” (Bryant 84). She goes on to mention that there is a correlation between employment and attractiveness. This idea of employment basically tells Black women that they are unemployed because they are unattractive, causing Black women to think this as well. In the larger scheme of things, this idea is damaging to Black women’s self-perception because it is further telling Black women that they are unattractive because of their skin color; to put it bluntly, they are ugly because they are Black.

Beauty standards also harm Black women by undermining their beauty. For instance, in an article titled, “Images of Women’s Sexuality in Advertisements: A Content Analysis of Black- and White-Oriented Women’s and Men’s Magazines” author Christina N. Baker shows how Black beauty is undermined within popular magazines. Within the findings of her article she states,

Similar to previous findings, images of Black women in mainstream media were still

uncommon. This means that the mainstream image of sexuality and beauty is still highly

associated with Whiteness. Another aspect of this is that even though there are very few

Blacks in mainstream magazines, the ones who are pictured often have European-like

physical features. This confirms and emphasizes the racial hierarchy of sexual

attractiveness in mainstream society. (Baker 26)

This quote emphasizes the larger idea of whiteness and European features being the standard within society as I alluded to earlier. This quote also mentions the main way that this undermining of Black beauty occurs, through representation. The first thing which Baker mentions is that Black women are rarely present in the “mainstream media”. The second thing that she mentions is that the Black women who are shown appear to have “European-like physical features” (Baker). So, not only are Black women un-represented but they are also misrepresented. This means that they are always portrayed in conversation with whiteness, never as just themselves which undermines the individual beauty of said Black women. In Cynthia L. Robinson’s article, a similar point is made within the conclusion. She says, “Problematic for many Black females is the unfeasibility of fitting African hair textures into European hairstyle choices. Unstraightened, the shorter, tightly coiled, or kinky hair textures can be difficult to comb, style, and manage. Yet, it is the kinkiness that allows the creative diversity of popular Black hairstyles that, ironically, makes bad hair particularly good for unstraightened styles” (Robinson 372). Though this article is talking about hair, it still alludes to the fact that racialized beauty standards undermine the beauty of Black women. Here specifically it mentions that the diverse hairstyles that are unique to Black women are only possible with “bad hair” or hair that doesn’t fit the standard. However, these hairstyles and hair types are unappreciated, as well as deemed unacceptable, because the straight and wavy hairstyles—of white women—are deemed beautiful.

In retrospect, beauty standards are a tool that have been used to uphold ideas of white supremacy which continually cause harm to Black women in particular. These beauty standards cause harm to Black women by damaging their self-perception and undermining their beauty. Rapunzel and other classic fairytales have been used throughout the late 20th century and early 21st century to push the agenda of beauty standards. Nowadays television, films, and mainstream media are used to propagate these ideas. Through similar hiring practices like the ones described within Susan L. Bryant’s article, lots of actresses on screen are white or possess features that make them appear within great proximity to whiteness. Blackness and Black beauty are left out of the conversation of beauty and oftentimes Black beauty is put down by these same racist images within the media.

One example of a modern television show that has perpetuated these messages is the sitcom Martin, that features an all-Black cast, starring Martin Lawrence. It is a comedy which focused on the daily experiences of Martin and his girlfriend Gina, a light skinned Black woman. However, when we take a closer look at the interactions between Martin and Gina vs Martin and his neighbor Pam, a brown skinned Black woman, we can see the ways in which racist ideas of beauty are encroached upon viewers. Martin was not only married to Gina but also constantly praised her looks, hair, and overall beauty. Whenever Martin saw Pam, he would constantly berate her: often mentioning her darker skin and comparing her physical appearances to beasts or wild animals. This was a running gag throughout the 5 seasons of the show. By putting Gina on a pedestal for her lighter skin and European-like features, Martin perpetuated racist beauty standards as well as degraded Pam, a dark-skinned Black woman for simply not fitting the standard.

In general, beauty standards cause immense harm to Black women but an analysis of them begs the question of are Black women the only ones who are suffering from them? By relegating people to beautiful or ugly and judging their worth solely off this standard are we not damaging our own perception? Are we not forcing ourselves to only look at what is external as opposed to seeing both the external and internal qualities of each other? This outward bias forces us to judge each other incorrectly and undermines our own individual humanity. We are all unique, a world with only one way of viewing things lacks the capacity to progress.