By Amy Carlyle

Fairy tales seek to communicate themes and messages to readers, using people and magic as metaphors for idea we can apply to our own lives. Often intended for children, fairy tales rely on simplicity and repetition; they should be brief and easily understood, and often, their motifs and components are quickly recognizable. Film and television projects aim to take stories, often with the same structures and traits, and deliver them neatly to audiences. Through analyzing common fairytale tropes and classifications, we can identify generalization in media where the pursuit of a simple, clear narrative sacrifices the complexity that real stories and people innately offer. To demonstrate this, I will examine the life of Diana, Princess of Wales, and subsequent projects about her life produced after her death in 1997.

The constant media attention surrounding Diana, even long after her death, memorializes her life story and transforms it into fairytale, ascribing to it different classic fairytale identifiers. Cliff Skelliter, a museum curator, organized a traveling exhibit commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Diana’s death. On the media coverage of her life, he said: “There is a lot of connectors to what feels like a fairy tale. We love fish-out-of-water stories because they act as a way for us to project ourselves easily into the character” (Roberts).

Diana’s story is complete with uses of Propp’s functions. She exemplifies Counteraction and fights back as she begins to dress to her own standard, not the crown’s, in response to how Charles treats her. Reconnaissance, Delivery, and Trickery come into play as the tabloids devour everything they can about Diana, spying on her to get information, publishing that information, and using fragments of truth to manipulate her into interviews such as her famous sit-down with Martin Bashir (Vargas). Throughout this time, of course, Diana experiences significant Struggle. Instead of a happily-ever-after, complete with Propp’s Solution and Wedding, Diana’s life was tragically cut short.

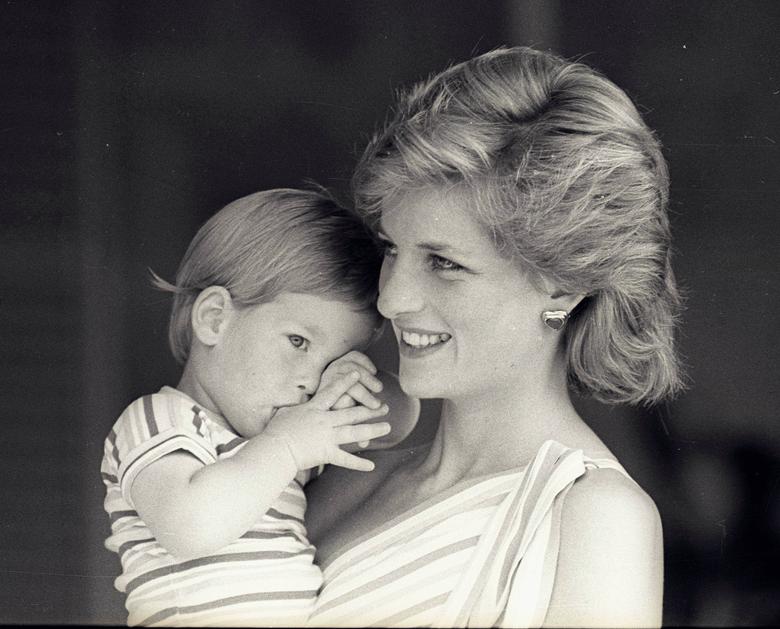

In addition to the plot of Diana’s story containing fairy tale components, the people in her life are also often reduced into their most obvious part for the screen. For example, critic favorite Spencer trims the excess off of the royals so audiences have easier characters to follow. The filmmakers characterized “Charles as a careless and unloving husband, the royal family aloof and controlling, and Diana as a romantic innocent, loving mother, betrayed spouse and forever, triumphantly, the people’s princess” (Roberts). In making the characters so clear cut, these characters are becoming stereotypes of who they were or could have been. Charles’ actions towards Diana and others remain true, but the royals’ family dynamic and marriage were certainly more complicated than what can be communicated in ninety-minute film, and while Diana often comes out on top in these narratives — the people’s princess, a victim to the cruelty of the monarchy — she too becomes merely a character over time. Diana has been cast as a protagonist in her own life’s tale, her community categorized into those who celebrated her and and those who betrayed her.

Commodifying Diana’s story into a fairy tale allowed her story to remain a fixture in the global public memory for longer. Fairy tales are made concise and brief over time as they are passed down by generations — often orally, especially centuries ago. Diana is survived by how writers and producers have chosen to represent her; audiences remember her most potent interview phrases that are repeated in every documentary and book chronicling her, leaving her less iconic moments to be forgotten. Despite the new works that are produced about her, like the recent Broadway musical Diana or film The Princess, moments are re-aired and repeated. “It’s all, rather, frustratingly stale: the same familiar footage. The same acknowledgments of Diana’s cultural influence on Britain and the world. The same vaguely voyeuristic exposés of her struggles … The same celebrations of her as a mother and humanitarian” (Hampson).

In addition to extending her social shelf life well beyond her death, the fairy tale dramatization of Diana’s life allowed her story to reach more people. Her youngest son, Prince Harry, said in the documentary Diana, Our Mother, “…I was thinking to myself, how is it that so many people that never even met this woman, my mother, can be crying and showing more emotion than I actually am feeling?” (Vargas). The narrative of Diana in media promotes an adult emotional attachment to Diana reminiscent of children’s attachments to Disney princesses, attachments founded on inspiration and awe. “When somebody like Diana comes along, all these women who were around the same age, now in their 60s and 70s, projected themselves onto this young lady and forged this strong bond,” said Skelliter about exhibit patrons (Roberts).

The consequence of building this narrative and making a fairy tale of Diana is the reductive nature of what her character becomes. In retelling Diana’s life this way, the audience views a whole person through a two-dimensional lens. On this, Roxanne Roberts wrote for the Washington Post:

The story of Diana started like a fairy tale and ended like a Greek tragedy: a handsome prince, a beautiful princess, then fame, betrayal, reinvention and a fatal car crash 25 years ago in Paris … While Charles has calcified into a state of permanent suspension, Diana has been transformed into an archetype, a symbol of resilience and redemption. She is Everywoman, or what every woman wants her to be.

(Roberts)

This phenomenon is complicated by the fact that a substantial number of projects covering Diana have come out after her death, and aside from family input sought only out of courtesy, Diana and those who actually knew her have little to do with them. Diana’s story is taken out of her own hands as others, in her absence, decide for her how best to tell it. On a documentary relying on recordings of Diana to convey her story, Hampson wrote: “It is right somehow – and moving – that she tells her own story, her real feelings, against the images the world created and consumed. Everyone has had a say about Diana, even now her sons. Twenty years later, we should let her have the last word” (Hampson).

With the benefits of establishing Diana’s life as an essential pop culture narrative, storytellers also risk reducing her into what can be made into a spectacle for profit and viewership. To take the full story of Diana’s life — all 36 years — and extract only the most quintessential moments and characteristics to pass on through stories limits the scope of how well the world can truly know her. As Roberts wrote, she becomes more symbolic than anything else, as did the other royals, with Charles a disloyal husband and Camilla a villain. Diana did not necessarily fit in with the family she found herself surrounded by, but her struggles became impersonal: the public knows only the moments others found worthy of sharing, and as audiences forget the specifics of those moments, we hold onto only the emotions we had while watching. She becomes no longer a person with her own unique experiences, but a figure emblematic of the feelings audiences may have about their own circumstances. She becomes a vehicle for understanding theme in another director’s or writer’s plot, just how fairy tales can educate or caution us about something.

The glamorized and dramatized depiction of Princess Diana in media forces her story into the established fairy tale molds. Without her voice represented to its fullness, Diana is simplified into a character and her memories, both struggles and celebrations, are transformed into plot points. In selectively retelling her life experiences this way, the media reduces her personhood to make it more consumable for audiences, in turn underreporting the nuances of her circumstances and the details that made her a complete person. In memorializing Diana as a globally beloved princess denied her happily ever after, her life has been converted to fairy tale, a story that can be passed down for years to come but never with the full truth and substance she carried.

Works Cited

Remembering Princess Diana: Her Life in Photos. Reuters. 29 Jul. 1981.

Garber, Megan. “Diana, Princess of Tales.” Columbia Journalism Review, https://archives.cjr.org/the_kicker/diana_princess_of_tales.php.

Hampson, Sarah. “A Troubled Fairy-Tale: Princess Diana Remembered 20 Years Later .” The Globe and Mail, 23 Aug. 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/a-troubled-fairy-tale-princess-diana-remembered-20-years-later/article36064254/.

Michel, Uli. Remembering Princess Diana: Her Life in Photos. Reuters. 23 Jul. 1986.

Peralta, Hugh. Remembering Princess Diana: Her Life in Photos. Reuters. 9 Aug. 1988.

Roberts, Roxanne. “Princess Diana Died 25 Years Ago but Endures as a Role Model for Women.” The Washington Post, 28 Sept. 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2022/08/20/princess-diana-death-anniversary/.

Vargas, Chanel. “How Prince William and Prince Harry Reacted to Their Mother’s Death.” Town & Country, 30 Aug. 2022, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/tradition/a10372852/prince-william-prince-harry-talk-about-princess-diana/.