By Garett Collins

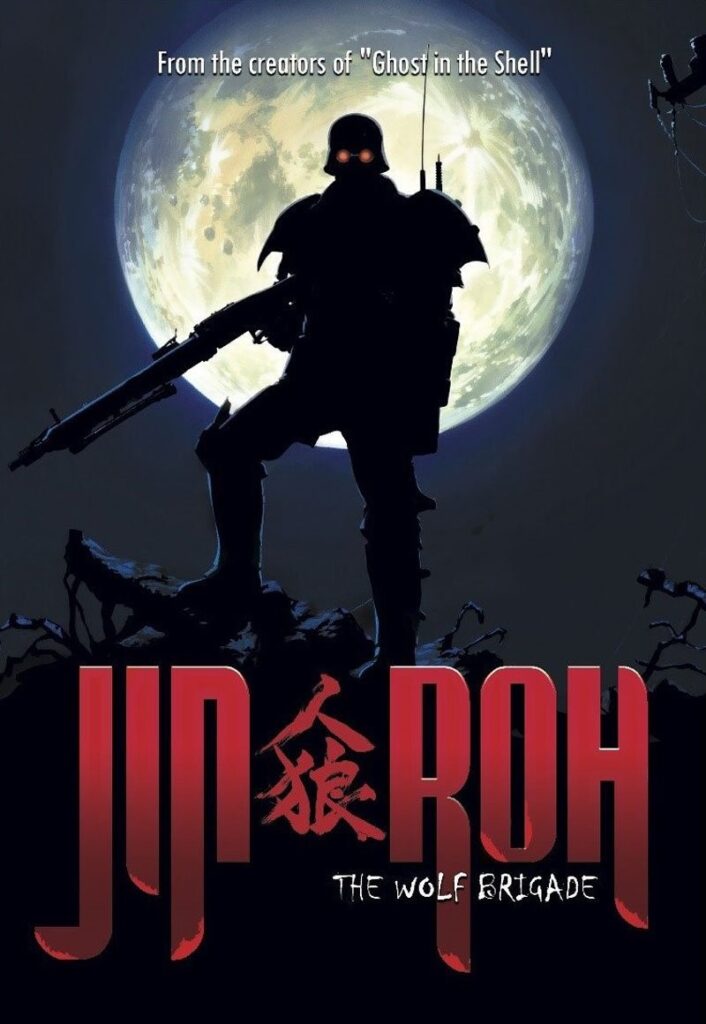

The tale of Little Red Riding Hood has, since its earliest literary conception in 1697 at the hands of Charles Perrault, become inexorably linked to the concept of fairy tales as a genre. Enduring in a near-universal capacity for its timeless morals, the story of a little girl and a voracious predator has appeared in numerous derivations across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Traditional fairy tale derivations of the little red riding hood archetype were often directed at children, utilizing the anthropomorphic “wolf” to symbolize the vast unknown, and the concept of the dangerous stranger. In this way, the wolf often represents temptation, desire, and broadly speaking, all that is evil. The “red hood” in turn represents innocence, order, and the concept of good. While the fairy tale medium proved sufficient to convey the binary predator-prey relationship central to many iterations of ATU (Arne-Thompson-Uther index) 333 to its intended audience, the natural limitation of such a narrative choice is that the story cannot effectively present its morals without defining the predator and prey figures as fundamentally opposite, incompatible entities. The practical result of this literary structure is that it cultivates an extremely linear, simplified interpretation of the message. Fairy tales often carry the connotation of being exclusively for children because of this genre-defining simplicity, however, the dissemination of fairy tale archetypes, including the Little Red Riding Hood template, into broader types of media has allowed such stories to become more accessible to adult audiences, resulting in more complex and introspective interpretations of fairy tale elements. Both Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade and Perrault’s Little Red Riding Hood serve to cultivate virtues and contextualize macroscale fears such as fear of the unknown and loss of control by reflecting elements of their native cultures, however, Jin-roh is particularly significant in that it challenges the notions of definitive systems of values by presenting them to adults as ambiguous and multifaceted things, in turn forcing its audience to confront their perceptions of morality on a personal level as opposed to the definitive, linear depiction of morality present in Little Red Riding Hood, which was specifically designed to appeal to children.

The Rashomon effect is the concept that eyewitness accounts are innately unreliable or incomplete, and that the perception of any event is impacted by the observer’s frame of reference. This idea is apparent both in the narrative structure of much of modern media, with notable plot points being depicted from multiple perspectives to recontextualize the greater scope of the subject, and on a metatextual level due to its implication that the reception of a work is inherently affected by the audience’s frame of reference. This latter point manifests both on an individual and cultural level. In their 2013 paper discussing the applications of the Rashomon effect on Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade, Pauline Greenhill and Steven Kohm of the University of Winnipeg assert that the movie presents a postmodernist perspective on the ambiguous nature of truth, storytelling, and a nonlinear concept of justice by manipulating the audience’s preconceived notions about the little red riding hood type story to continually subvert their expectations as more layers of the story are slowly revealed (Greenhill. 90). In this way, Jin-roh forces its audience to confront the notion that there simply is no definitive concept of truth, or binary systems of good and evil. This narrative decision itself is the product of the predominant global sentiments during its production in 1998, stemming from a post-World War II Japan wracked with the destruction and subsequent reconstruction efforts that heavily influenced several successive generations, and global tensions at the end of the Cold War; both of which contributed to the popular deconstruction of the hero and villain archetypes and helped cultivate morally ambiguous characters.

In stark contrast to the multifaceted reality depicted in Jin-roh, Perrault’s Little Red Riding Hood instead thrives on the extreme simplicity of its plot to convey an objective understanding of truth. There is a wolf, who is evil. There is a girl with a bright red coat who is innocent, and who does not know the danger of speaking to wolves. The short story, totaling only two pages from start to finish, is accompanied by a “moral” which states the author’s precise intention and, in doing so, functionally eliminates any narrative ambiguity the story might have otherwise contained. Perrault expressly states that his fairy tale targets “young girls, pretty, well bred, and genteel”, and was meant to teach them that wolves can wear many faces, and that if they were not wary the wolves would devour them (Perrault. 44). This absolute description made the story more consumable for younger audiences and proliferated in the collective consciousness because it presented eternally-relevant lessons that all children should be acquainted with; such as the value of skepticism, and that good little children should listen to their parents. The wolf is made to be scary, alien, and venomous to frighten children into internalizing values that will serve them as they develop, and the subtextual references to obedience and punishment for disobedience endeared the story to parents.

Even tales that are defined so clearly by the author are, however, subject to change alongside the society that observes them. Time and the analysis of many geographically and temporally varied cultures has given rise to many alternative interpretations of Little Red Riding Hood. Cynthia Jones, a specialist in French literature and artistry, posits that the strangeness that Perrault’s wolf was meant to represent was the seductive allure of the eponymous Little Red Riding Hood’s own innate animalistic nature, which she dubs the “anima”. The wolf’s consumption of the little girl would therefore represent the shedding of her purity (Jones. 130). Her red coat, which has become integral to the archetype, was also first described in Perrault’s version as a possible symbol of the young girl’s innocence, literally shrouding her from the darkness of the world but ultimately incapable of protecting her from the wolf’s jaws. Jones’s analysis is particularly significant in that it implies that the wolf and the girl are facets of the same individual. Still notably incompatible elements, as evidenced by the destruction of one to feed the other, but with significant implications for the later development of the story archetype. Maria Tatar, recognized as the preeminent authority on the matter of fairy tales and myth, expands on this principle in her lecture The Big Bad Wolf Reconsidered by charting the progression of Little Red Riding Hood-like tales through various mediums, demonstrating the profound effects of broadening fairy tales from exclusively child-oriented subjects into media designed for adults. One common avenue by which this transition is explored in adult media is through the rise of erotic film, Tatar explains, observing the predator-prey dynamic that serves as the focus for much of that narrative niche (Tatar. 31:10). Though sexual expression is considered a definitively adult act, such stories are not notably different from those fairy tales and books made for children, in that they present their story in a traditionally superficial way. Because the audience engages with these types of media with a specific intention in mind, social education in the case of children and sexual gratification in the case of adults, the narrative is better served by presenting itself in the most direct, comprehensible way, providing a notable example of traditional “wolf” and “red hood” archetypes being adapted providing a distinct benefit for heavily divergent audiences. This reflects the notion that audiences and their social and cultural niches shape media.

Tatar does, however, expand on the inverse notion that media can affect and reflect society as well. Peter Paik of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee discusses the effect of using the visual medium of animation to magnify the emotional impact of Jin-roh’s plot. Hiroyuki Okiura, who directed the movie, is largely known for utilizing a grounded, hyper-realistic style of animation. Immaculately detailed set pieces frame each shot and characters move through them with a sense of realistic weightiness, and expressions are depicted proportionally to their stimuli. With the exception of a singular scene occurring in the latter half of the film, “Jin-Roh would have worked just as well as a live-action thriller of political conspiracy and inter-governmental espionage” (Paik. 110). Why, then, was the movie produced as an animation? Animating the story in such an intimate, meticulously real manner allowed Okiura to achieve a sort of hyper-reality where his characters were made more tangible than if they were portrayed by living, breathing humans. Fully animated characters have the additional benefit of disconnecting the roles from visible, possibly recognizable actors, shifting the focus from the characters themselves toward what the characters represent.

Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade is a story of monsters, certainly, but it reminds its viewers that not all monsters are external. The story revolves around an elite counter-terrorism operative, named Kazuki Fuse, struggling to come to terms with his role in a chaotic post-World War II Japan. After witnessing a little girl commit suicide-by-bombing during an anti-government riot, Fuse begins to question his role as a “wolf” and is overcome by guilt for what he views as his greatest failure. It is not until he meets Kei Amemiya, who claims to be the young terrorist’s older sister and appears in a cherry red coat, carried over from Perrault’s rendition and the later adaptation by the Brothers Grimm, that he apparently begins to come to terms with himself. The pair bond over their shared strangeness in a society that was never really their own, and what seems to be the first flicker of love begins to bloom. As the story progresses, however, it is revealed that Kei was planted by a rival police faction to incriminate Fuse in a political scandal that would destroy his organization. Betrayed, Fuse falls into what appears to be Kei’s trap. After a brutal confrontation, Fuse takes Kei and flees back into the tunnels where the young terrorist had killed herself, pursued by the remains of his opponents. Only upon entering the tunnels is it revealed that Kei had been coerced into incriminating Fuse, and that the latter had known for some time, having been instructed by his own superiors to bring the rival faction there. What follows is a brief but spectacularly bloody and tense slaughter at Fuse’s hands. Kei, broken both by the guilt of her own actions and the sudden realization that she had apparently been used by her mark and the man she grew to love, doesn’t resist when she is taken out of the city to be executed. Fuse at first resists this notion arguing that her death would serve no purpose, but is firmly denied as his superior places a gun in his hand. They embrace one final time as Fuse pulls the trigger.

Jin-roh is largely unique in that both of its main characters are simultaneously the “wolf”, and the “red hood”. Fuse is, by nature of his position in a paramilitary organization known for its brutality, presented as a predator and a monster, yet he refused to fire on the young terrorist despite her attempt to murder him. Kei, at first appearing as an innocent third-party, agreed to manipulate Fuse’s apparent weakness to reduce the punishment for her own criminal history. Fuse’s final act of killing Kei, the wolf ultimately devouring Little Red Riding Hood, serves a sort of absolution of the latter’s sin. In pulling the trigger, Fuse rendered his own humanity and fully accepted his nature as a wolf while also letting Kei die as a casualty of war, rather than a perpetrator of violence. Written for a primarily Japanese adult population still intimately aware of the incredible potential for human violence in the wake of World War II and the difficult reconstruction that followed, Jin-roh embraces the notion that people have within themselves the capacity to be both predator and prey, perpetrator and innocent, good and evil, and that finding the balance between these forces is what defines the human condition.

Perrault’s Little Red Riding Hood is a simple story. It’s definitive, linear narrative and clear accompanying moral were ideal for reaching his intended audience of young children. To most effectively teach his young audience the danger of strangers with silver tongues and the importance of obeying one’s parents, it is logical to present the wolf as a foreign entity that could attack Little Red Riding Hood. Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade, by contrast, thrives on the complexity of its narrative to keep its audience off balance and unsure of what is come in a way that feels uncomfortably like the ever-shifting nature of real life. It rejects the notion of a singular perception of truth, and forces its observers to confront the fact that “the wolf” is not simply a foreign entity that can avoided or escaped, but an intrinsic presence in all people. The choice Jin-roh presents is not in whether a person is a “wolf” or a “red hood”, but rather how they choose to balance those two facets within themselves. Because Jin-roh was geared toward adults and the murky, complex, and ambiguous ponderances they have likely encountered, it was able to push the theme in uncomfortable and deeply introspective ways that would not have had the same potency and impact under different genre constraints or contemporary experiences.