Grob, Virginie. Aurora, Belle, and SnowWhite. 2011, Deviant Art.

By: Katelin Dunagan

Fairy tales are so popular because of their similar themes, tropes, and character types. Readers feel comforted knowing who the real heroes and villains are, unlike in the real world. They root for princes to save their passive, delicate maidens and despise evil queens for being wicked. However, these classic fairy tale archetypes can affect more than just a person’s grasp of a story being told. Fairy tales have distinct psychological effects on those who read them; they affect people’s personalities and interactions with others, expectations and expressions of behavior, and even views on social status and class.

Fairy tales affect readers through each story’s characters. These characters maintain roles that are easy to understand. Each character serves a specific purpose to either aid or obstruct the heroine in the story. Russian fairy tale expert, Vladimir Propp, classifies these character types as dramatis personae. The dramatis personae types include the following: a villain, donor or provider, helper, princess (sought-after person), and her father, dispatcher, hero, and false hero. Using the Grimm’s “Cinderella” to demonstrate this model, characters can be organized into their dramatis personae with the main villain being the stepmother, the princess being Cinderella, the donor or provider being Cinderella’s father, the helpers being the birds, the hero being the prince, the dispatcher being the king’s announcement, and the false heroes being the stepsisters (Tatar 160-166). Essentially, every fairy tale contains character types that fit into the dramatis personae framework, and “Cinderella” is just one example of this.

Cinderella. Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske, RKO Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, 1950.

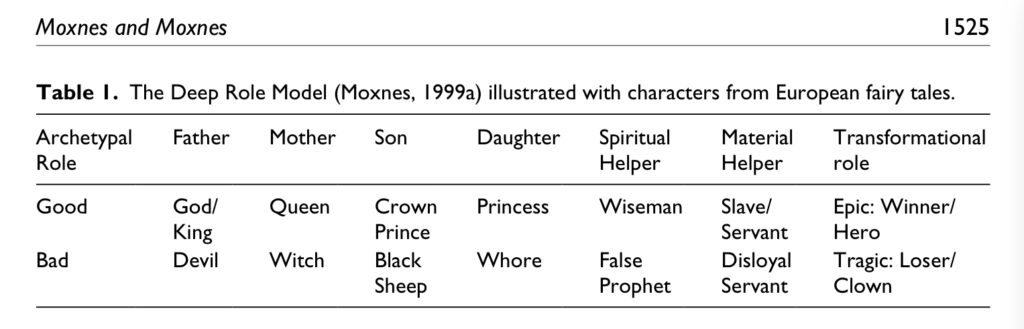

Propp’s dramatis personae structure is also a just singular representation of the many classifications of fairy tale characters into types. Based upon these different structures of classification, psychologists have been interested in the connections between character roles and human behavior. Psychologist Carl Jung contributed to these ideas, “proposing that it was primarily unconscious fantasies and symbols that steered human actions,” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1522). Inspired by Jung’s archetypal views, Paul and Andreas Moxnes created a study that examined the connection between fairy tale roles and group work.

Their study involved developing fourteen roles representing, “14 fairy tale characters” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1526). These roles are based upon seven archetypal roles, with a good and bad version of each role. The good and bad versions or “deep roles” are “a subset of seven instinctual archetypal roles split into antithetical components portrayed as four primary family roles plus three supplementary roles, each split into a good and bad part” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1525). For example, under the archetypal role of “Mother,” they created the deep roles of “Queen” and “Witch” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1525). The “Queen” corresponds to the good part of “Mother” and contrasts perfectly with the bad part, the “Witch.”

Moxnes, Paul & Moxnes, Andreas. “Are We Sucked into Fairy Tale Roles? Role Archetypes in Imagination and Organization.”Organization Studies, vol. 37, num. 10, 2016, pp. 1519-153.

After developing the fourteen roles, Moxnes & Moxnes had each participant assign everyone in their group to one of the roles. They determined how similar each person’s assignments were to the rest of the group. They found that their “quantitative observations strongly suggest that group members attribute fairy tale roles to fellow group members in a non-random fashion far more often than would be expected by chance alone” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1535). The study surpassed the threshold of chance and found that many participants identified a group member as the same character type chosen by other members of their group. While this is not confirmation that every person in a group identifies others as fairy tale characters, it supports the idea that people are affected by fairy tale character types, even if it is on a subconscious level.

This is important information for those involved in fields where teamwork is key. Character types can parallel stereotypes that brand people as one thing or idea. It can be difficult to share or contribute high-quality work if someone is branded as the “Witch” on their team. That person becomes controlled through “projective identification” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1534). This is a psychological concept where the stereotyped person, “becomes a character in the group that is created by the group and controlled by the group” (Moxnes & Moxnes 1534). They can subconsciously mirror the behaviors that their peers project onto them and act as the group sees them. Understanding how fairy tale roles impact a group can help keep harmful stereotypes from causing negative consequences such as projective identification.

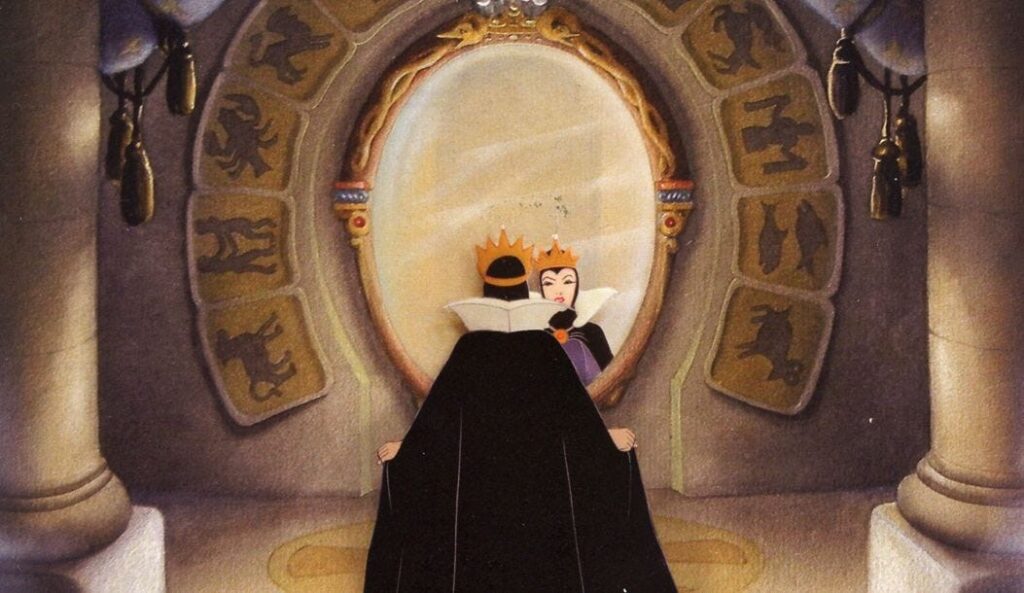

It has been determined that there is support for fairy tale characters influencing people’s views of one another but how does this apply to people’s views of themselves? For young women specifically, fairy tales often set unrealistic expectations of purity and selflessness. In both “Cinderella” and “Snow White,” the heroine, “endures her plight virtuously, seemingly without hostility or even complaint. Her salvation and happiness rest on winning the love of a prince, who has the power to rescue her” (Bassen 238). This communicates the idea that women shouldn’t have autonomy or express their negative emotions towards others.

This is problematic for young women facing coming-of-age conflicts comparable to those portrayed in these tales. These stories perpetuate unhealthy standards of emotional expression for a group that already, “consciously or unconsciously equate asserting themselves with being selfish and unlikeable” (Bassen 248). Women shouldn’t be afraid to be advocates for themselves or to strive for success. Unfortunately, this issue stems from conflict in relationships between mothers and daughters as well as patriarchal influences. Bassen describes this saying, “Unconsciously, many women believe that the only way they can retain their mother’s approval and love is to remain dependent, a carbon copy or a narcissistic extension who denies any wish to separate, compete, or surpass” (249). In essence, to keep their mother’s approval, daughters believe they must not be more successful, desirable, or free-thinking.

Through recognition of the mother-daughter opposition, one can prevent harmful habits from seeping into other relationships as well. An imbalanced mother-daughter relationship can affect that daughter’s eventual interaction with a partner. Bassen notices this behavior in some of her psychological patients as they became afraid of their partner’s anger, stemming from their relationship with their mother (249). Fairy tale readers must understand that “Snow White” and “Cinderella” handle coming-of-age and mother-daughter conflict poorly. They dismiss natural emotional responses to situations and reinforce outdated concepts of how women should behave. However, they do demonstrate that mother-daughter conflict has occurred for centuries and that it is an issue most women will face at some point in their lives. With the appropriate lens, one that highlights the shortcomings of these tales, there is a lot to be gained from reading these stories. As long as one is not negatively influenced in their perception of themselves.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Directed by David Hand, Perce Pearce, Larry Morey, Wilfred Jackson, William Cottrell, and Ben Sharpsteen, RKO Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, 1937.

The last way fairy tales psychologically influence readers is through ideologies and social structures. In “Beauty and the Beast” by Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont, there are very distinct social classes present that play a major part in the tale’s wish fulfillment. Beauty’s family, “are an upwardly mobile merchant family,” that has fallen upon hard times and is forced to farm and lower their status (Rucki & Ortiz 43). Eventually, Beauty meets the Beast, and throughout the story, they form a partnership that leads to marriage. Notice, that Beauty’s family do not start as peasants or farmers originally, which makes Beauty’s eventual rise in class more acceptable. She was once close to the class she would rise into, so it is more acceptable for her to marry into nobility with the Beast.

Beaumont is using his 18th century, aristocratic perspective, to structure his tale according to the class system he wants to uphold. He does this by incentivizing the virtues he deems appropriate. For example, Beauty, when compared to her sisters, is, “…neither prideful nor social. She is kind, loyal, self-sacrificing…” (Rucki & Ortiz 42). She contains the virtues Beaumont believes women of status should have and therefore she is rewarded with a rise in nobility. He is influencing his readers to accept and understand this structure as the social rule.

Beauty and the Beast. Directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1991.

This tale is a very effective piece of persuasive propaganda because it will be read by the exact demographic Beaumont intends to reach. The upper aristocratic women he believes should embody more virtuous, selfless behaviors. It can also be dangerous; it is an example of conditioning readers to do as the author wishes. They may not realize this is what is occurring because it is in the form of a fairy tale. This kind of conditioning influences readers and familiarizes them with a “correct” social structure, in this example, it is the structure Beaumont supports.

It is evident that fairy tales have profound psychological effects on readers. Through their archetypal characters, fairy tales shape perceptions of self and others and reinforce outdated behavioral expectations. They influence readers concepts of social structure by leveraging happiness and wish fulfillment. Only through critical examination of these tales, can valuable insights be pulled from the stories without negative consequences. While fairy tales continue to enchant and captivate audiences, it is essential to approach them with a discerning eye, mindful of their ability to shape beliefs and attitudes in both subtle and significant ways.

Works Cited

Bassen, Cecile R. “Happily Ever After: Depictions of Coming of Age in Fairy Tales.” Psychoanalysis and Women Series, edited by Tognoli Pasquali, Laura & Thomson-Salo, Frances, Karnac Books, 2014, pp. 237-254.

Beauty and the Beast. Directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1991.

Cinderella. Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske, RKO Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, 1950.

Grob, Virginie. Aurora, Belle, and SnowWhite. 2011, Deviant Art.

Moxnes, Paul & Moxnes, Andreas. “Are We Sucked into Fairy Tale Roles? Role Archetypes in Imagination and Organization.”Organization Studies, vol. 37, num. 10, 2016, pp. 1519-153.

Rucki, Shelia M. & Ortiz, Lisa. “Hegemonic Systems and the Politics of Happiness: The Fairy Tale as Ideology.” Perspectives on Happiness: Concepts, Conditions, and Consequences, vol. 121, 2019, pp. 1570-7113.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Directed by David Hand, Perce Pearce, Larry Morey, Wilfred Jackson, William Cottrell, and Ben Sharpsteen, RKO Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, 1937.

Tartar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales (Second Edition) (Norton Critical Editions). W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.