By Peter Cooper

When observed from the perspective of a modern viewer, original fairy tales are to say the least odd. Gruesome violence and sexual allusions are certainly seen as oddities, and a great many of the ideas are very very much outdated. Why then do we tell our children these stories? Simply because we were told them as children? Well in part yes, we tell our children these stories because it is tradition, and in the words of Donald Kingsbury, “Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems. Throw away the solution and you get the problem back. Sometimes the problem has mutated or disappeared. Often it is still there as strong as it ever was.” (Kingsbury 179). However in our age, we have new problems, a new culture, a new reality, the stories that became our fairy tales don’t address some of the problems we haven’t forgotten. This exercise therefore is to take the formula of the fairy tale, and adapt it to the context of the modern day to prove that the fairy tale, though a phenomenon most associated in the past, is not necessarily exclusive to stories of a bygone age. Fairy Tales and their similarities are the result of the shared purpose of explaining adult problems to children, and therefore can

be recreated to regard modern issues due to the consistency of the nature of childhood.

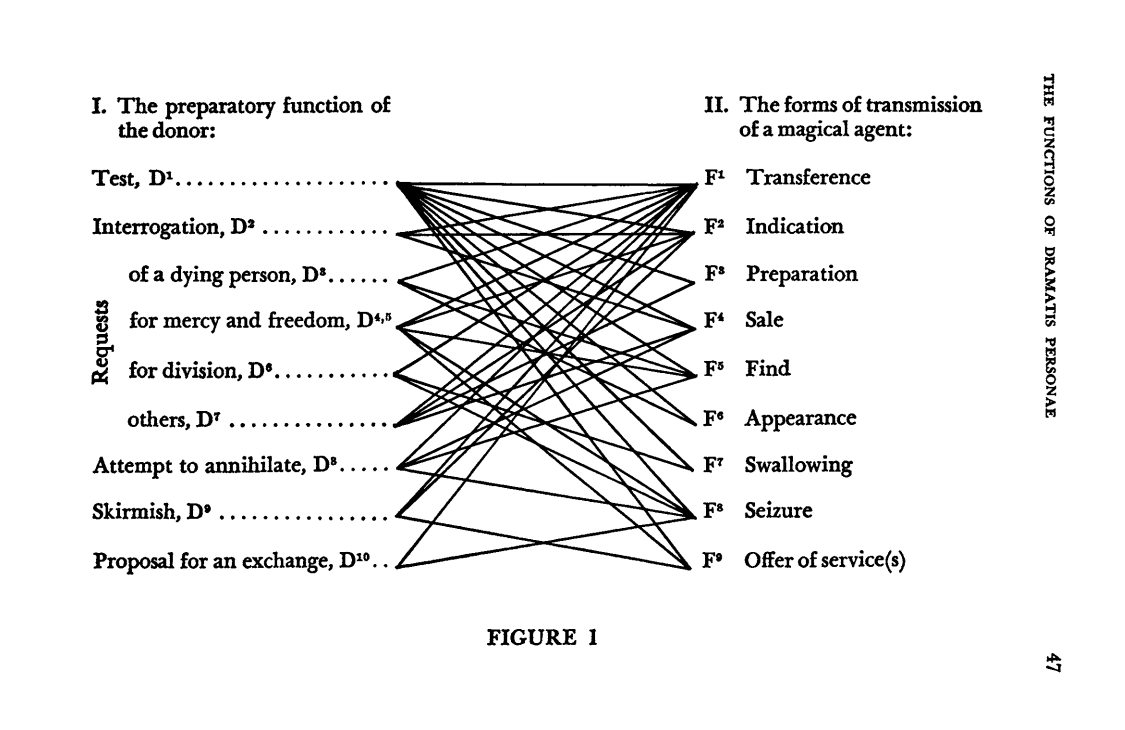

To start, let’s look at some of the past efforts to reduce fairy tales to their basest elements to inspect what really makes up a fairy tale. The most prominent scholarly effort to categorize the basest elements of Fairy Tales is that of Vladimir Propp. Propp’s work with the Arne-Thompson-Uther complex, (The Complex used to numerically categorize fairy tales,) are complicated to say the least, Propp made a conscious effort to encapsulate as many stories as possible, not only in exact structure, but in what specific tropes may beget others, as seen here:

(Propp 47)

This allows us to ensure the story maintains a familiar flow to it, and though Propp’s work in this regard is a tool for classification rather than creation, ensures we are in line with tradition. Propp further worked in creating a structure that defines 31 series of events that make up a fairy tale. Propp’s functions are not universally agreed upon, and nowadays are considered relatively conservative, and many modern scholars argue “Every narrative has its own distinct number of functions” (Murphy 473). However the framework of Propp’s functions is suitable in the effort of creating the modern Fairy tale. Propp’s work gives us a structure and guidelines within which we may write our modern Fairy Tale.

The next aspect that must be considered are the more textually substantial aspects of the fairy tale, such as conflict, setting, and characters, of these, Conflict is the most vital and it is from there our story derives the majority of its plot. To this end we must implement the first modern variable into our formula, the lesson. In the words of a psychology professional: “Fairy tales use their conflicts to teach to children These make-believe stories that often reflect reality give children the opportunity to nurture their imaginations and teach them about situations and feelings they can face in real life,” (Kolonko), this indicates the goal of the fairy tale, and allows us to formulate conflict by mimicking a real life goal children May face. In the interest of modernity I’ve elected to use a more modern issue, that of the internet scam. Therefore our conflict will come from a gullible protagonist being deceived by our antagonist and learning his lesson.

The next aspect to address is the matter of the setting, what is “Once Upon a Time?” We do not want our setting to be perfect, as so many modern interpretations do, for the fairy tale is not to create what scholar Jack Zipes resentfully referred to as “enchanting dreamworlds that lure the eye,” (Zipes 136), but to impart a lesson. To that end an urban environment would be the closest equivalent of the “Dark Forest” of a fairy tale. The time period is also often an important part of the setting, we want it to seem fantastical yet familiar, as advancements in technology were more stagnant when fairy tales were being created; this is a more difficult endeavor now. Fortunately Fairy tales exist in a sort of space outside of time, allowing for a mixture of elements as the story requires.

Finally the Characters, as people’s nature does not change too much this is a fairly straightforward process. First the protagonist, as usual a child will serve to allow for easier relatability, and he needs something to lose so making him a prince will do. It may seem counterintuitive to maintain a monarchy in a modern story, but we strive for timelessness, and forms of monarchy are very much still abundant. The Antagonist simply needs to be an intimidating creature. A wolf is often used here but in the interest of engagement I will use a creature equally familiar to children but far more exotic to them, the velociraptor. Next the Donor, according to Propp it is “ from him that the hero (both the seeker hero and the victim hero) obtains some agent (usually magical) which permits the eventual liquidation of misfortune.” If we have a prince it would be suitable to have a Queen to be his mother and parental guide.

To sum up the effort, I have utilized Propp’s 31 functions, as well as his work on proper sequences of events to put together a story that intends to serve the purpose for our age that fairy tales did for theirs. As an exercise for a writer and scholar I’d say it was a success, but I leave the Judgment of the work itself up for the interpretation of the reader. Without further ado, I present:

The Prince and the Velociraptor

A Modern-Day Fairy Tale

By Peter Cooper

Once upon a time there was a young prince, who lived in a large palace in the big city. Every day the prince would put on his fancy clothes and his silver crown, and leave his mother and father in their palace and set off to explore the city. Before leaving his mother, the Queen would always warn him “Help who you can, but be sure people are who they say,” The prince, thinking his mother was too old to know how things were anymore, would roll his eyes at this. One day, this interaction was overheard by a sneaky velociraptor passing by the Palace. That day as the prince walked along the street he was approached by the velociraptor, who said to him. “Ah a prince, hello good sir, I too am a prince”

“How wonderful,” Replied the prince, “What can I do for you?”

“Well” Responded the Velociraptor, “I need to go reclaim my place among the dinosaurs, but I’ve lost my crown. Let me borrow your silver crown and I promise to return with a golden one by sundown.”

The Prince obliged and allowed the dinosaur to borrow his crown, and agreed to meet him in the same spot at sundown. When he returns home the Queen asks,

“Son, where is your silver crown?”

“I let someone borrow it, but they’ve not returned”

The queen shook her head, “If it is lost you must retrieve it.”

“I gave it to another prince.”

“How do you know?”

“He told me.”

The queen simply shook her head “Son, I told you You must be sure people are who they say, you are to go to bed, tomorrow you must retrieve your crown.”

The Prince did as he was told and set off the next morning, given a coin from his mother to pay for his travel to the dinosaur’s neighborhood. However the prince, embarrassed of being deceived, elected to use another tactic, He snuck back into the house and made a crown of tin-foil he then showed it to the Queen.

“Dear Mother, look! I am not as foolish as you thought, the velociraptor returned with my crown, look I still have your coin as well.”

The Queen Squinted, “I am not foolish either, I know tin-foil when I see it. This time I will go with you to ensure you do as you say.”

And with that the Queen took the prince to the dinosaur neighborhood, urging him not to return until he had retrieved his crown. The Prince searched high and low for the velociraptor, trying desperately to find him, every once and a while the prince would catch a glimpse of him but he would dart away before he could catch him. Eventually the prince came up with a solution, He took his tinfoil crown and placed it on the ground and hid, eventually the velociraptor came to grab it, as he bent down, the prince swooped in, took the crown and ran off. But the velociraptor was in pursuit and quickly gaining, so the young prince began to pick shiny rocks from the ground and throw them behind him, yelling “My gems are falling from my pockets.” The trick worked, and the Velociraptor doubled back to pick up the rocks. Soon enough the prince had returned to the palace, crown in hand and presented it to his mother, but he was shocked that the velociraptor had beat him there.

“Son.” Said the Queen, “This fine creature has returned to me your crown, I was just about to reward him.” The Queen held up the tinfoil crown.

“It’s a lie mother,” Replied the prince, “This is the real crown, that one is made of tinfoil, look.”

The Prince presented his mother the crown, she squinted to inspect them.

“Goodness me you’re right! I suppose we’re both a tad gullible.”

The queen then put the Silver Crown on her son’s head, and the tinfoil crown on the velociraptor’s and banned him from entering the city ever again. The Prince and the Queen then promised each other to be far more careful who they trust, and they lived happily ever after, the end.

Works Cited

Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “Fairy-Tale Origins, Fairy-Tale Dissemination, and Folk Narrative Theory.” Fabula 47.3–4 (2006): 211–221. Web.

Kingsbury, Donald. Courtship Rite. SFBC Science Fiction, 2006.

Kolonko, Catherine. “How Do Fairytales Affect Child Development? Benefits and Downsides.” Psych Central, Psych Central, 8 Feb. 2023, psychcentral.com/health/pros-and-cons-of-exposing-kids-to-fairytales.

Murphy, Terence Patrick. The Fairytale and Plot Structure. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. Web.

Propp, V. I͡A. (Vladimir I͡Akovlevich). Morphology of the Folktale. 2nd ed., rev.edited with a pref. by Louis A. Wagner, new introd. by Alan Dundes. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968. Print.

Zipes, Jack. Fairy Tale as Myth/Myth as Fairy Tale. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1994. Print.